| City/Town: • Birmingham |

| Location Class: • Commercial • Community |

| Built: • 1922 | Abandoned: • 2011 |

| Historic Designation: • National Historic Landmark (2017) • African American Heritage Site • Historic District (1982) |

| Status: • Under Renovation |

| Photojournalist: • David Bulit |

Table of Contents

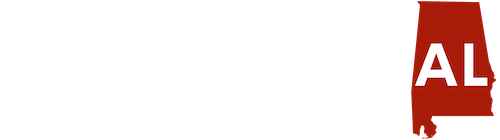

Colored Masonry in Alabama

Colored Masonry in Alabama came into existence approximately 1867, two years after the end of the American Civil War. By 1869, there were between eight and ten properly and traditionally recognized local lodges of Masonry. These lodges operated under charters issued by the states of Ohio, Tennessee, and Missouri.

On September 27, 1870, the Masters, Wardens, and other legal representatives of the subordinate lodges gathered at a convention at the colored Masonic Hall in Mobile to form a Colored Grand Lodge known as the Independent Most Worshipful Grand Lodge, Ancient Free and Accepted Masons of Alabama. Another Colored Grand Lodge was formed in 1874 known as the National Compact Grand Lodge. These two Grand Lodges operated independently until August 13, 1878, when the two Grand Lodges were consolidated to form the Grand Lodge of Alabama, Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge, F. & A. M. of Alabama.

At the time of consolidation, the Grand Lodge was composed of 22 warranted lodges and a membership of approximately 300. Today, the Grand Lodge is composed of 235 actively functioning subordinate lodges with a membership of approximately 6,000. In 1913, under the leadership of Grand Master Walter Thomas Woods, another state convention voted to raise funds in lieu of taking on any debt for the construction of a Grand Temple for their Grand Lodge in Birmingham. Over the next seven years, $750,000 was raised from Masons throughout Alabama.

Fourth Avenue Historic District

According to Ann M. Burkharrdt, Research Coordinator for the Birmingham Historical Society, the Fourth Avenue Historic District is deemed significant as it is “the only place left in the city which tells the story of the Jim Crow years in Birmingham (1908-1941). Prohibited from patronizing white restaurants, movie theaters, and personal service establishments, blacks developed businesses in those areas to serve their community. They also offered professional services (medical and legal) to the black community. Although now somewhat diminished by the demolition of some structures and the dispersal of black life that has come with integration and suburban expansion, important structures remain which document what was once the center of commercial activity in black Birmingham.”

The district includes the former Davenport-Harris Funeral Home, the city’s oldest black mortuary; Carver Cinema, one of the three best examples of the Art Moderne style in the city; Famous Theatre, the oldest movie house remaining in the district built for the black community; the Champion-Savoy Theatres Building, the only building remaining in the district which offered live entertainment for the Black community; and the Alabama Penny Savings Bank which was likely designed by prominent black architect Wallace A. Rayfield and housed the state’s first black-owned bank and offices for the black press, business and professionals in the city. It was here within the city’s black social and business hub that the state headquarters of the Prince Hall Masons would be located.

Colored Masonic Temple

Officially known as the Masonic Temple Building, the Colored Masonic Temple was designed by African American architects Robert Robinson Taylor and Louis Hudison Persley. Taylor was the first African American graduate of the United State School of Architecture and in 1892 became the first African American graduate of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Upon graduation, Booker T. Washington offered Taylor a position to develop the industrial program at the newly-established Tuskegee Institute and to design and direct the construction of a new building on the campus. Between 1892 and 1932, Taylor designed most of the Tuskegee buildings, collaborating with Carnegie Tech graduate Louis H. Persley during the last decade.

At a cost of $750,000, the Colored Masonic Temple was constructed by Windham Brothers Construction Company, Birmingham’s leading African American construction company during the first half of the 20th Century. Constructed of brick and limestone, the building features a rusticated limestone base, fine brickwork, Corinthian columns and pilasters, classical cornice and pediment, graduated pilasters and cornices, and Roman grills at the attic story. The cornerstone was laid in 1922 and the Masonic Temple officially opened on April 1, 1924. At the time, it was described as “the largest and best-equipped office building built and paid for by Negroes in the entire world.”

In addition to housing the state headquarters for the Prince Hall Masons and the Order of the Eastern Star, the building also leased office space to notable African American professionals, businesses, and organizations, as well as a drug store and soda fountain on the ground floor. The second-floor auditorium had a capacity of 2,000 and hosted numerous meetings, ceremonies, weddings, banquets, and graduations. The auditorium also provided a venue for concerts and big band orchestras, including those of Duke Ellington and Count Basie. Both men were Prince Hall Masons, as were Alabama as were other music greats such as Nat King Cole, Lionel Hampton, and Birmingham native Erskine Hawkins.

Tenants

Including the many meeting halls in the Masonic Temple were the offices of many black dentists and doctors such as that of Dr. Florita Earlene Jamison Askew, one of the few female dentists in the building. She was known as “ReeRee” to her friends and family and was the daughter of Dr. Earle S. Jamison.

The offices of Dr. Robert M. Howard was located on the 5th floor of the Temple. He was born July 17, 1925, in Blue Field, West Virginia. He graduated from West Virginia State University in 1942 and was a World War II veteran. After graduation, he continued his studies at Meharry Medical College in Nashville, Tennessee, and earned a Doctor of Dental Surgery Degree. Dr. Howard began and continued practicing dentistry for over 50 years in the Masonic Temple. He was also the company dentist at Stockham Valves and Fittings for over 35 years until it closed. During his service to the community, he received numerous awards and honors.

The office of Dr. Joseph Price Pearson was also located on the 5th floor, down the hall from Dr. Howard. Pearson was born on April 11, 1902, the son of Jim and Laura Price Pearson. His father Jim was a masseur and chiropodist and operated a Turkish bathhouse out of a small residence located at the time on what is now the site of the Robert S. Vance Federal Building. Later in life, he founded the Birmingham Institute which slowly grew from simple log cabins to a small community with dormitories, a school, a tuberculosis sanatarium for Blacks, and a church.

Joseph Pearson graduated from Birmingham High School and Miles College before receiving his doctorate from the Illinois College of Chiropody. He later received his bachelor’s degree from the Alabama State College for Negroes. He served as dean of his father’s Birmingham Institute and practiced medicine for much of his life with his offices located on the fifth floor of the Masonic Temple.

Booker T. Washington Library

In October 1918, the Booker T. Washington Branch Library opened at 1713 Third Avenue North, the first to loan out written works to black citizens in Birmingham. By 1923, the library’s collection of books numbered 5,425 and a circulation of 45,000 books per year, most of which were purchased with funds raised by Dr. John Herbert Phillips, superintendent of Jefferson County Colored Schools.

To meet the needs of the library’s growing impact on the city’s black community, it was moved into the ground floor spaces of the newly built Masonic Temple in October 1923. The library expanded into adjoining commercial space in 1927, and into additional rooms on the opposite side of the building’s entrance in 1933. A smaller collection of books was later held at the Slossfield Community Center after its construction in 1937.

In 1953, a study was conducted on the city’s library system which found that while Booker T. Washington Library had one of the largest book collections of any of the city’s libraries, its circulation figures had significantly declined. At the suggestion of a white board member to improve the use of the city’s two black branch libraries, the Birmingham Public Library Board organized a “Negro Advisory Committee.” Carol H. Hayes, director of Birmingham African American schools, E. Paul Jones, director of Jefferson County’s Division of Negro Education, and Mrs. M. L. Gaston, head of the Booker T. Washington Business College, made up the committee.

The committee quickly organized a publicity campaign that boosted circulation by 20 percent and the number of visitors by 33 percent. In response to the success, the Negro Advisory Committee sought to expand services and requested additional funding from the board. One board member suggested that a central library for the black community be constructed which was argued to be an unnecessary and costly duplication of what was already established. Despite objections by some of the board members, the Smithfield Library was constructed in 1956. That same year, the Booker T. Washington library’s collection was moved from the Colored Masonic Temple to the newly built library on 8th Avenue West.

Atlanta Life Insurance Company

Located on the 6th floor of the building is the former office of The Atlanta Life Insurance Company which was founded in 1905 by Alonzo Franklin Herndon. He was born on June 26, 1858, in Walton County, Georgia, the son of Sophenie, an enslaved woman, and Frank Herndon, her enslaver who was from a wealthy slaveholding family. Following the American Civil War, Alonzo and his family were emancipated, taking on his father’s surname and entering freedom in destitution. He worked as a laborer on plantations in Social Circle, Georgia, to help support his family.

In 1878, Herndon left Social Circle and settled in Senoia, Georgia, where he worked as a farmhand and learned the barbering trade. He later opened up his first barbershop in Jonesboro, Georgia, and was quite successful, later expanding the business over the years. Eventually, he owned and operated three barbershops in Atlanta. One of them, “The Crystal Palace” which he opened in 1902 at 66 Peachtree Street, was considered the most elegant in the country.

Through Atlanta’s Wheat Street Baptist Church in 1905, Herndon bought a small self-help association known as the Atlanta Benevolent and Protective Association for $140. He also acquired two other small businesses, the Royal Mutual Insurance Company and the National Laborers’ Protective, and reorganized them as the Atlanta Mutual Insurance Association. By 1915, Atlanta Mutual had become one of the largest Black insurance companies in the South.

In September 1922, the company was reorganized as Atlanta Life Insurance Company and became one of five African American insurance companies at the time to achieve legal reserve status. By 1924, the company had expanded to other Southern states including Florida, Alabama, Kansas, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Texas. Today the Atlanta Life Insurance Company is the second largest African American-owned insurance company in the United States, operating in 17 states with about $200 million in assets.

A. A. Peters, Endowment Secretary

Professor A. A. Peters was born in 1856 and served as principal of schools covering nearly a 40-year career before being elected Grand Endowment Secretary of the A. F. & A. M., Jurisdiction of Alabama. Having served as Endowment Secretary for 15 years, Peters suddenly dropped dead in his office on the seventh floor of the Masonic Temple on the morning of December 31, 1926.

His funeral service was held in the main auditorium of the Masonic Temple with more than 2,000 people, officers, members, and friends crowding into the room at the opening hour to pay their respects. Notable attendees included Bishop B. G. Shaw of the A. M. E. Zion Church and William Thomas White, the son of United States Senator Francis Shelley White and partner in the law firm of Frank S. White & Sons. Dr. C. L. Fisher of the Sixteenth Baptist Church read the scriptures and Dr. G. W. Mitchell, Right Worshipful Grand Chaplain of the order, Mobile, AL, prayed the opening prayer.

Grand Master Walter Thomas Woods served as master of ceremonies and spoke in the highest terms of Peters’ life and work. He said, “When Brother Peters was elected endowment secretary of the order we owed the widows and orphans of this state $100,000, and not a record of the endowment department in hand and none to be found. He struggled along patiently and sacrificingly. We wiped out the $100,000 debt, installed new records, and continued the fraternity in Alabama. You must know that it was a struggle to pay this large sum of money without a dollar and nothing to rely upon but the books of the deceased and what meager expressions we could find in subordinate lodges. More than $2,000,000 during this period passed through his hands and he has never been a penny short.”

Following his death, his son Charles W. Peters, former master of Lodge #107, Girard, Ala., was appointed Endowment Secretary of the order.

Civil Rights Movement

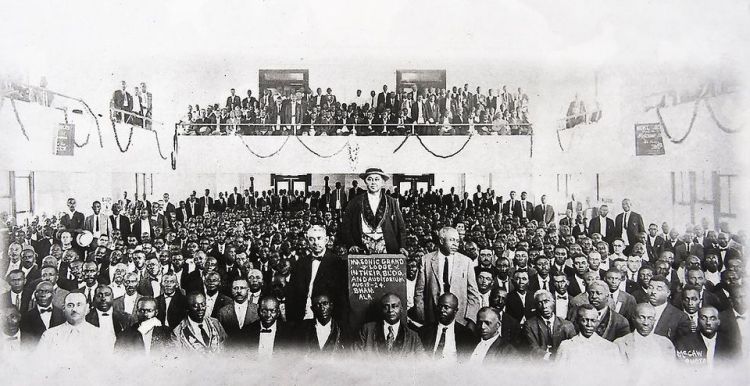

The city’s white Masons required that their members remain non-political and often criticized black Masons for allowing political events to be held at the Masonic Temple. Faced with police brutality, segregation, the denial of voting rights, and fair housing, local African Americans felt they didn’t have the luxury of remaining non-political.

On October 2, 1932, the Masonic Temple auditorium hosted a civil rights conference organized by the Communist Party-affiliated International Labor Defense. This was in response to the infamous Scottsboro Boys trial in which nine black teens were wrongfully accused of raping two white women. Police surrounded the building to intimidate the attendees while white protestors threatened everyone who entered the building. The conference was one of Birmingham’s first major civil rights events, setting the stage for future civil rights actions in the city.

Hosea Hudson

Hosea Hudson, a local African American iron molder at Stockham Valves and Fittings who had been fired for union organizing and his affiliations with the Communist Party, had attended the conference that day. In November 1933, Hudson and other members of the Communist Party organized a meeting towards Union rights for black industrial workers. The meeting was raided by police with eight of the nine organizers being arrested. Hudson and another organizer were held in the Birmingham jail and charged with holding a Communist Party “meeting to overthrow the government.” Hudson plead not guilty and was released the following afternoon.

Hudson later organized a “Right to Vote Club” to help poor and working-class Blacks navigate Alabama’s voter registration process. He also held voting clinics in rooms he rented at the Masonic Temple. Whenever Club members were denied their right to vote, Hudson filed discrimination charges and was represented in court by NAACP attorney Arthur Shores.

NAACP v. Alabama

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) Southeast Regional Office was located in Room 624 of the Masonic Temple with Regional Secretary Ruby Hurley coordinating the organization’s programs throughout Alabama, Florida, Georgia, and Mississippi. Due to the NAACP’s increasing effectiveness in Alabama, Attorney General John M. Patterson filed a lawsuit in 1956 against the NAACP claiming that the organization had harmed the citizens of Alabama by promoting, among other things, the Montgomery Bus Boycott and aiding Autherine Lucy in getting admitted to the University of Alabama. According to Patterson, these activities were illegal as the NAACP had failed to register as an out-of-state organization.

The judge hearing the case, Circuit Court Judge Walter B. Jones, ordered the NAACP to cease operations immediately in the state pending a hearing to determine whether or not it was truly exempt from the requirements of the law. The doors to the NAACP offices in the Masonic Temple were padlocked following this order. Anticipating this outcome, Hurley had already moved the organization’s records across the street to the Birmingham World newspaper office where they remained for the next eight years.

At Patterson’s request, Judge Jones ordered that the NAACP produce a number of records relative to its operations in Alabama, including the names and addresses of its members. The NAACP initially refused, protesting that the order was a violation of the organization’s constitutional rights since it would, in effect, be forced to give evidence against itself. The NAACP was held in contempt of court and fined $10,000 but was offered a reduction or suspension of the fine if it produce the requested records within five days. If not, then the fine would be increased to $100,000.

In response, the NAACP produced many of the requested records within the five-day period but refused to turn over its membership lists citing that it exposed them to “economic reprisal, loss of employment, threat of physical coercion, and other manifestations of physical hostility.” It was also believed that complying with the order would dissuade present members and potential recruits from associating with the organization, which violated their constitutional rights of association and assembly. This action subjected the NAACP not only to higher fines but also to an Alabama law that halted all legal proceedings until the contempt order was discharged. This meant the hearing regarding the NAACP’s activities in the state could not proceed.

The Alabama Supreme Court refused to review the decision of the lower court, so the U.S. Supreme Court took the case, handing down its ruling on June 30, 1958. Writing for a unanimous court in NAACP v. Alabama, Justice John Marshall Harlan II declared, “This Court has recognized the vital relationship between freedom to associate and privacy in one’s associations…” The court added that the NAACP had the right to keep its membership confidential due to the consequences they would be faced with. Although the ruling overturned the contempt order and the $100,000 fine, the NAACP was unable to operate in Alabama until 1963, following several more appeals to the Supreme Court.

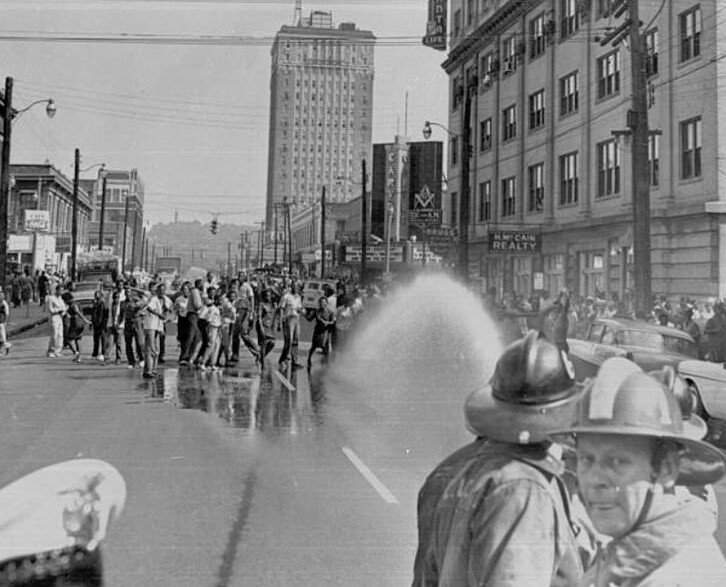

Birmingham Campaign

The Colored Masonic Temple played a significant role during the Civil Rights Movement in Birmingham in the 1960s. In May 1961, lodge members sheltered and cared for Freedom Riders who were beaten in Anniston, Calhoun County, and Birmingham’s Greyhound Bus Station. During the Birmingham Campaign in 1963, Martin Luther King Jr. visited the Temple where many protests and sit-ins were organized. The Masonic Temple also functioned as an infirmary for protestors who were beaten by police, hit with fire hoses, and attacked by dogs as they marched from the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church through Kelly Ingram Park located just a block away from the Temple.

Dynamite Hill

Located on Center Street was Dynamite Hill, a nickname given to the neighborhood due to the number of bombings that occurred there. This was quite a distinction in a city nicknamed “Bombingham.” Center Street acted as the city’s color line as the west side of the street was the white side and the east side was in transition. From the late-1940s, black families would often move into the white side, challenging Birmingham’s segregation laws. At first, the Ku Klux Klan would burn the doors of the houses that African Americans moved into. Sometimes they would fire shots through the windows. It wasn’t long before they started using dynamite.

The first bombing occurred on July 28, 1949, at the home of Reverend Milton Curry Jr. located at 1100 Center Street North. His house was bombed again on August 2, 1949, and a third time on April 22, 1950. People knew a blast was coming when they heard decommissioned police cruisers flying up the hill. The terrorists would throw dynamite at their intended target, usually landing on the porch or in the yard. After one bombing, a riot erupted on Center Street. People were throwing rocks and bottles at police officers who returned with gunfire, killing a man.

The home of Arthur Shores was bombed on August 20, 1963, and a second time a couple of weeks later. During an oral history interview with the University of North Carolina in 1974, Arthur Shores described the second bombing that took place at his home. He said, “Just as I got up to go outside… If I’d been a moment or two earlier, the glass would have caught me full in the face. Just as I got up to go outside. My front door was blown in. That time my wife was injured. She had retired. She had a concussion.” A third bomb was found

The last bombings of that era occurred in 1965 on April Fool’s Day. Shortly before 4 a.m., an explosion occurred behind the home of T. L. Crowell, an accountant with offices located in the Masonic Temple. The blast created a large crater in the alley and destroyed the Crowell family’s garage. The blast also cracked bricks and shattered windows of houses within a two-block radius. His son Weymouth received a cut on his hand as he got out of bed covered in shattered glass. All off-duty policemen were summoned to the neighborhood to comb the area for more explosives. The city also requested a demolition team from Fort McClellan to help with the efforts.

Across town, M. J. Miglionico was fetching the morning newspaper while his ailing wife and his daughter, a Birmingham councilwoman, were still sleeping. He found a green box on his porch and thought it was a gift of fruit or legal papers for his daughter. This wasn’t out of the ordinary as people have left paperwork for his daughter on their porch in the past. The box though was too heavy to bring inside… and it was ticking. He tore open the box and ripped out the bomb’s mechanism, throwing the clock and attached wires in the yard. He went inside and awakened his daughter who called the police.

At the suggestion of Councilman John Bryan, Captain J. H. Wooley and other officers set out to check other city officials’ houses. Mayor Albert Boutwell lived less than two blocks, but he was in Washington D.C. at the time meeting with other mayors and President Lyndon B. Johnson. Only his son Albert Jr. was home and slept peacefully and police rifled through the bushes around the family home. Outside his window, a green box was found. Having zero experience with explosives, Captain Wooley reached in and ripped the timer out, disarming the explosive. Although the culprits were never found, the Ku Klux Klan was suspected behind the attacks.

Closure and Redevelopment

By the 1990s, issues began arising with the building’s HVAC systems, and funds to keep the Masonic Temple operational were diminishing. In 2011, the last tenants moved out and the building was shuttered and left vacant for the next decade. During its vacancy, a security system was installed in the building following a fire that damaged a hallway by the main auditorium suspected to have been set by squatters.

Main Street Birmingham hosted a workshop at the Temple in January 2009 to bring about some ideas for its redevelopment. In 2017, shortly after the Colored Masonic Temple was made part of the Birmingham Civil Rights National Monument, the Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge launched a campaign to raise $10-15 million for the restoration and expansion of the Colored Masonic Temple. At the time, ideas were discussed to include a multi-story parking garage adjacent to the Temple with retail spaces located on the ground floor.

In November 2019, it was announced that the Grand Lodge was working with Historic District Developers, a venture of Henderson & Co. of Raleigh-Durham, North Carolina with Direct Invest Development LLC of New York, on a $30 million mixed-use redevelopment of the building. Urban Impact Inc. and the Birmingham Department of Innovation and Economic Opportunity also participated in the project, which was intended to qualify for Historic Preservation Tax Credits, New Market Tax Credits, and Opportunity Zone tax credits.

In April 2022, Historic District Developers began the process of removing, cataloging, and archiving artifacts that remained in the building. They will be checking with the Masons’ preservation committee, which includes a retired historian, to see if any of the documents or other items are worth saving. Project manager Llevelyn Rhone told WBRC FOX6 that “In addition to that, we are assembling a larger group of folks from both museums, academic circles, as well as libraries who will also be working once these items are packed up to literally go through each of the boxes and determine what is actually relevant and can and should be cataloged.” Construction is set to begin once the process is completed.

Photo Gallery

References

Historic American Buildings Survey, Library of Congress. (1993). Masonic Temple (Colored), 1630 Fourth Avenue North, Birmingham, Jefferson County, AL

The Birmingham News. (retrieved August 1, 2022). ROBERT HOWARD OBITUARY

The Birmingham News. (retrieved August 1, 2022). FLORITA ASKEW OBITUARY

Alabama NewsCenter; Michael Sznajderman. (July 29, 2021). Birmingham Masonic Temple: ‘Bringing life back to these walls’

MIT Black History. (retrieved August 8, 2022). Robert R. Taylor, First Black Student at MIT

Encyclopedia of Alabama; Steven P. Brown. (March 21, 2008). NAACP v. Alabama

The First Amendment Encyclopedia; Sekou Franklin. (2009). NAACP v. Alabama (1958)

Birmingham Post-Herald; Howell Raines. (April 2, 1965 p. 1). Reward Fund Up To $50,000; FBI Bomb Experts At Work Here

Most Worshipful Grand Lodge F & A. M. of Alabama. (retrieved August 1, 2022). Our History in Sweet Home Alabama

National Register of Historic Places. (February 11, 1982). Fourth Avenue Historic District