| City/Town: • Tuscaloosa |

| Location Class: • Community |

| Built: • 1829 | Abandoned: • 1923 |

| Status: • Burned Down |

| Photojournalist: • David Bulit |

Table of Contents

Old Alabama State Capitol Building

The story of the old Alabama State Capitol Building begins in 1825 with the abandonment of the frequently flooded city of Cahaba. Alabama legislators faced the task of selecting a new seat of government. Tuscaloosa, strategically situated in proximity to a majority of white settlements during that era, was designated as the new capital and held this status from 1826 to 1846. This designation marked Tuscaloosa as the third state capital, succeeding Huntsville, which served as a temporary capital in 1819, and Cahaba, the capital from 1820 to 1825.

Tuscaloosa was at the time a thriving community located on the shoals of the Black Warrior River and had been a strong candidate for the capital site when Cahaba had been chosen in 1819. However, Tuscaloosa became increasingly inconvenient as a seat of government for the rapidly growing state. As Indian counties opened to white settlement, Alabama’s population gains were concentrated in the state’s eastern counties. This led to a need for a more centralized capital. That of course was the reasoning for the state’s newest and current capital, Montgomery, which has served since 1846. However, remnants of Tuscaloosa’s time as the capital endure to this day.

William Nichols, Architect

William Nichols designed the capitol as his first project in his new position as the state architect of Alabama. He was also responsible for designing many plantation homes and government buildings throughout the South.

Born 1780 in Bath, England, a prominent hub for English Palladian and Adam-style architecture during the 18th century, William Nichols was raised in a family deeply involved in the construction trade. His early education in the craft came from his familial ties, providing him with a solid foundation in the art of building. In 1800, Nichols embarked on a journey across the Atlantic, choosing North Carolina as his new home and initially settling in the New Bern area.

In 1805, Nichols married Mary Rew, and by 1806, he had already taken on his first apprentice, showcasing his commitment to passing on his skills and knowledge. While the exact details of his earliest commissions in the region remain somewhat unclear, several buildings have been proposed as potential candidates, underlining the significant impact Nichols had on the architectural landscape. Seeking to fully integrate into his adopted homeland, Nichols applied for American citizenship in 1813. His wife Mary Rew died in 1815. Nichols remarried, taking Sarah Simons as his second wife.

North Carolina State Architect

In 1818, William Nichols assumed the role of state architect for North Carolina, a position that bestowed upon him the responsibility of overseeing the construction of new state buildings and managing repairs and enhancements to existing structures. One of his most significant undertakings during this period was the comprehensive renovation of the old North Carolina State House, a project he completed in 1822.

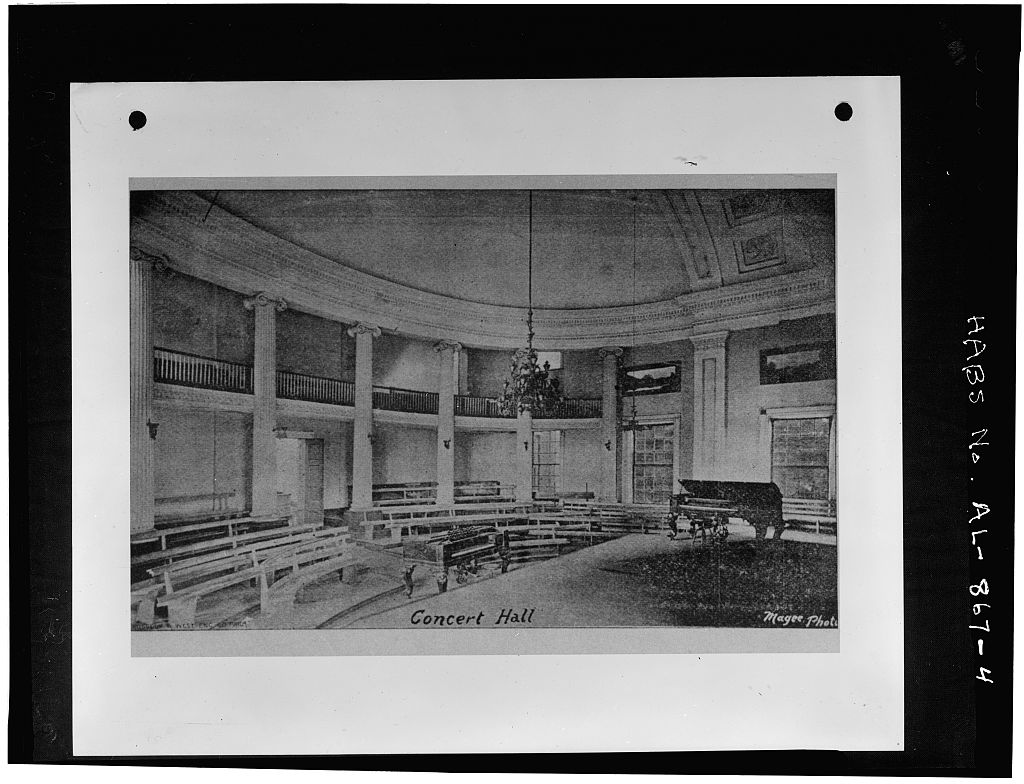

Nichols’ redesign of the State House was a masterful blend of Palladian and early Greek Revival elements. The renovated structure featured a new central rotunda crowned by an elegant dome. Notable additions included galleries supported by Ionic columns in both the Senate chamber and the House of Commons. Widely celebrated during its time, Nichols’ work on the State House garnered praise from fellow architect Ithiel Town, further solidifying his reputation as a skilled and innovative designer.

Among his other notable projects, Nichols was commissioned in 1825 to remodel the Governor’s Palace located at the end of Fayetteville Street in Raleigh. This ambitious undertaking involved the addition of a grand Ionic portico, lending a monumental and classical aesthetic to the historic structure. Unfortunately, the Governor’s Palace, abandoned after the Civil War, met its demise through eventual demolition.

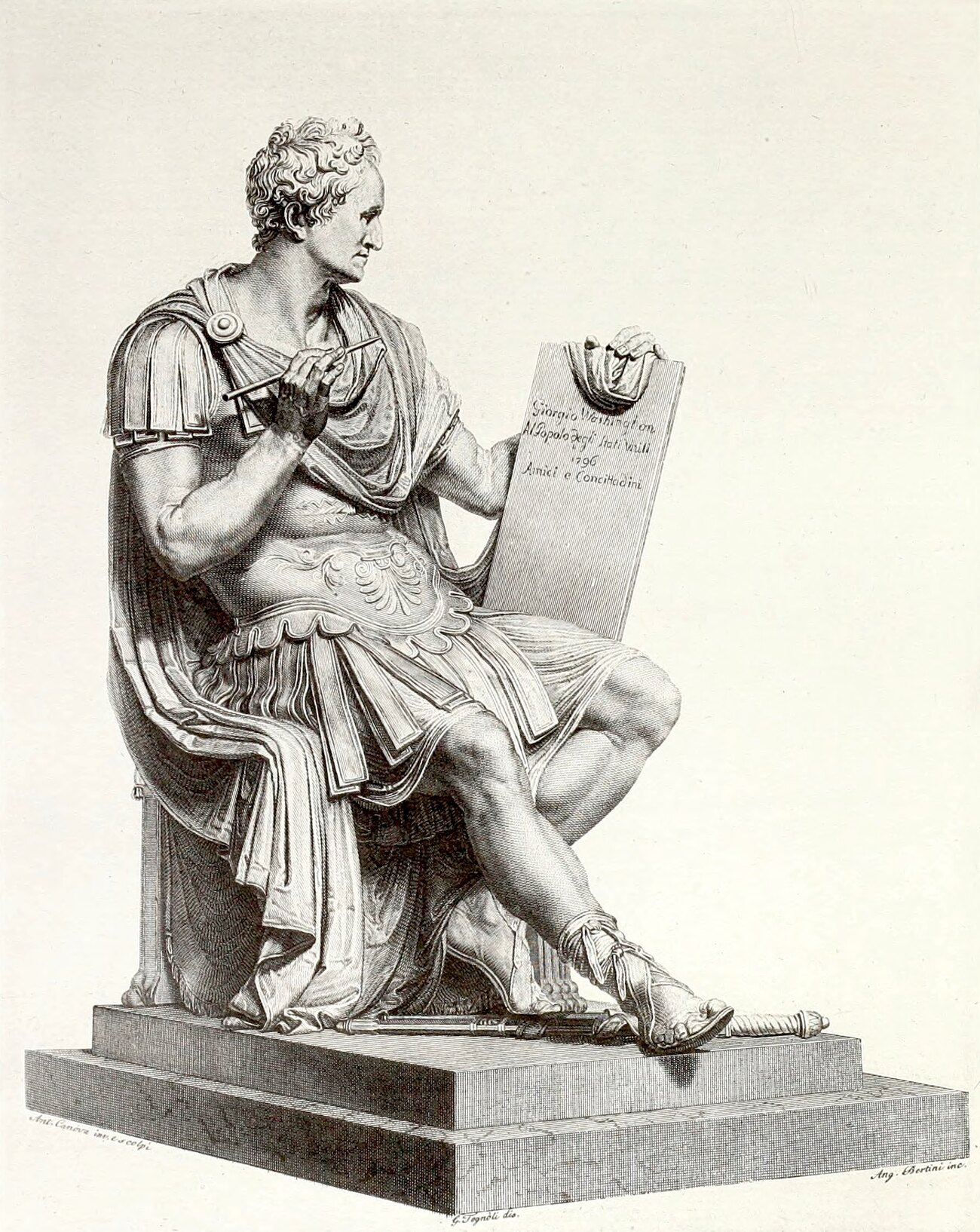

In 1815, the State of North Carolina commissioned Venetian-Italian Neoclassical sculptor Antonio Canova for a life-size marble statue of George Washington, done in the style of a Roman general. The statue was completed in 1820. Nichols designed specially modified wagons that oxen pulled to move the statue from Fayetteville to Raleigh. One wagon held the statue while another carried the base. The statue was installed in the rotunda of the North Carolina State House on December 24, 1821, and was destroyed on June 21, 1831, when the building burned to the ground.

Alabama Architecture Works

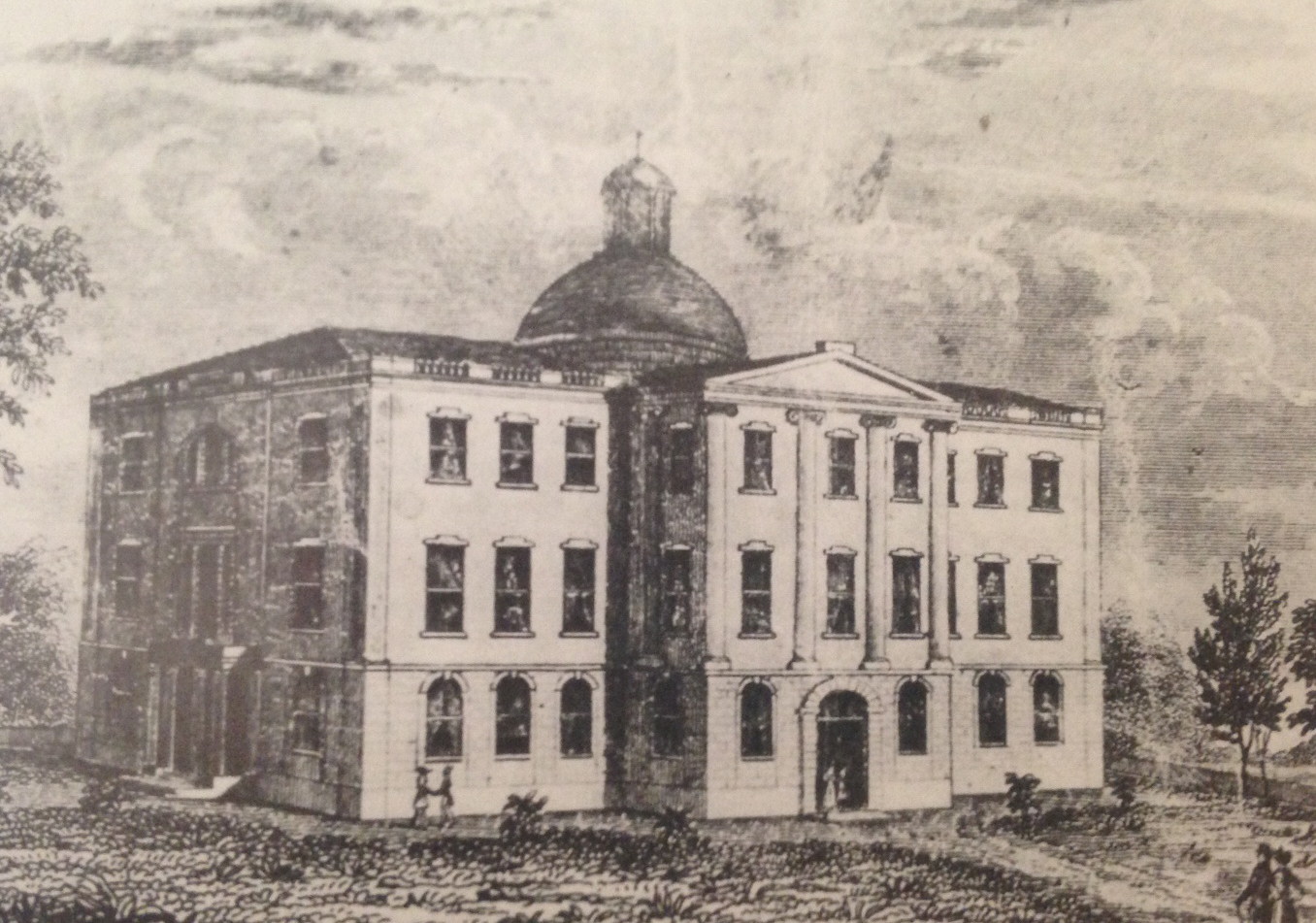

While working on designing the Alabama statehouse, Nichols also designed the original campus for the newly established University of Alabama. Influenced by Thomas Jefferson’s plan at the University of Virginia, the campus featured a 70-foot wide, 70-foot high domed rotunda building that served as the library and nucleus of the campus. This building and all but one of Nichols’ structures were burned to the ground by the Union Army on April 4, 1865.

His other works in Alabama include the Christ Episcopal Church in Tuscaloosa, the historic plantation houses Thornhill and Rosemount in Forkland, and the Forks of Cypress in Florence.

Mississippi State Architect

In 1833, Nichols was recommended by his friend, Alabama Governor John Gayle, and applied for state architect of Mississippi. Although he didn’t receive the job then, he was later called to Jackson, Mississippi in 1836 to oversee the completion of the Mississippi State Capitol building, replacing architect John Lawrence. The replacement was due to issues with Lawrence and the use of substandard materials.

Nichols went on to design the Mississippi Governor’s Mansion, completed in 1842, and the Lyceum at the University of Mississippi, completed in 1848. He died on December 12, 1853, and was interred in the Odd Fellows Cemetery in Lexington, Mississippi.

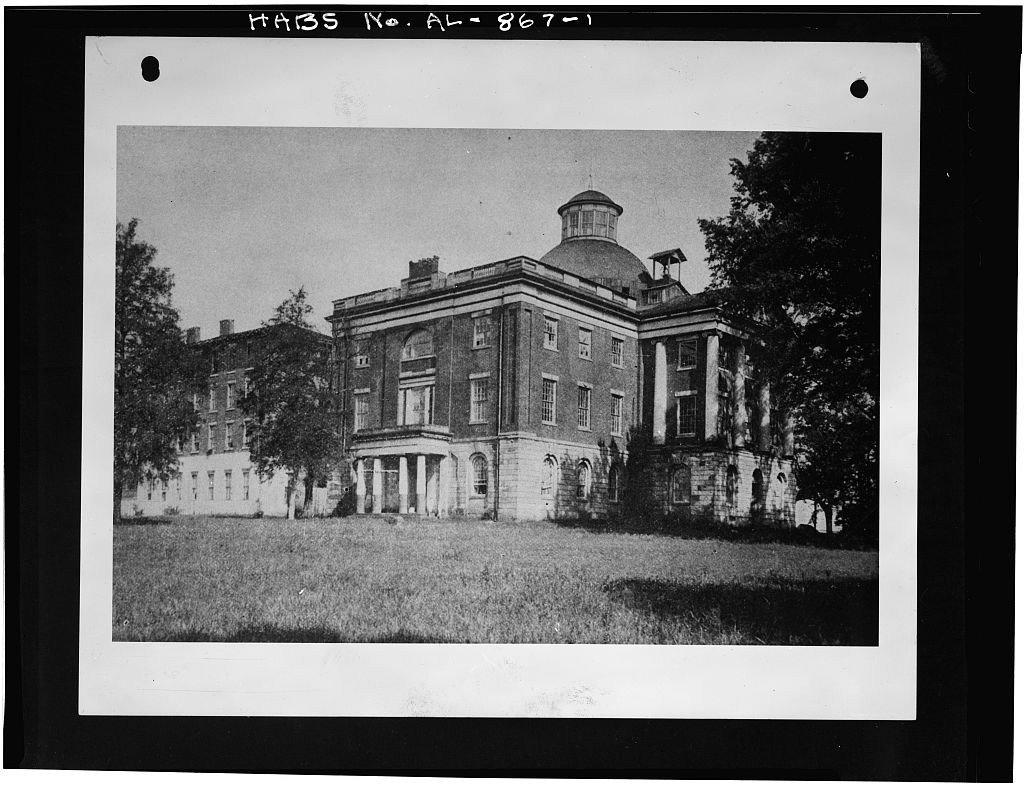

Architecture of the Alabama State Capitol

According to an article by the University of Alabama, “In the structure of the Greek Cruciform, the State House featured three main wings and an entrance hallway. The Supreme Court’s chamber was in the smaller west wing of the building, while the north wing contained the Senate’s chamber, and The Hall of the House of Representatives was in the south wing.

Both the north wing and the south wing contained a gallery for spectators, with the south wing’s gallery being smaller than the north. The main entrance was built on the east side of the building. On the exterior, the first story is decorated with rusticated stone, with red brick siding continuing up the remaining two stories. The first story was built in heavily rusticated freestone from Tuscaloosa, while the two stories above were made of brick brought over the river from Northport.

The three wings were united by a large common rotunda area, under the structure’s central dome. A lantern exists at the top of the dome in order to naturally light this central area. The symmetrical facade along with with the separation of each state legislative branch on opposite sides of the building imply an even separation of powers between the three, a reflection of the structure of American government common in the Federal style.

A cornice around the perimeter of the building separates the first story from those above. Entrances at the north and south sides of the building feature one-story tall porticoes with Doric columns of sandstone, in the design of Peter Nicholson’s Corby Castle facades. The facade of the main entrance at the east side of the structure displayed two-story tall Ionic pillars, extending from the top of the first story’s rustication to the pseudo-portico atop of the building’s east side.

Both the belfry and the dome on the final building were built at ground level and raised to the top of the structure, above the central 90 foot tall rotunda. The original sheathed copper dome was known to leak, and sometime before 1890 was recompleted with wood shingles.“

Abandonment and Burning of Tuscaloosa’s Capitol Building

In November 1846, Montgomery was chosen as the new capital city because of its proximity to most of the settlements in the state and its location along the Alabama River, which provided a convenient mode of transportation to the capital.

After Tuscaloosa was abandoned as the state capital, the former capitol building was used by the Alabama Central Female College until 1923. On August 22, 1923, the building burned. The fire was attributed to faulty wiring. The ruins were preserved to mark Tuscaloosa’s time as capital. The ruins are the focal point of Capitol Park located at 2828 Sixth Street in Tuscaloosa.