| City/Town: • Linden |

| Location Class: • Community |

| Built: • 1850 | Abandoned: • 1973 |

| Historic Designation: • National Register of Historic Places (1974) |

| Status: • Abandoned |

| Photojournalist: • David Bulit |

Table of Contents

The Town of Linden

Settled prior to 1818, the community was first known as “Screamersville”, since one could hear the cry of wild animals throughout the night. Marengo County was created by the Alabama Territorial legislature on February 6, 1818, from land acquired from the Choctaw by the Treaty of Fort St. Stephens on October 24, 1816. Like the other four of the “Five Civilized Tribes”, over the course of the following twenty years, the Choctaw were largely forced west of the Mississippi River and into Indian Territory, what is now Oklahoma. The county was named after Napoleon Bonaparte’s victory at the Battle of Marengo and in honor of the county’s first European settlers; Bonapartists exiled from France after Napoleon’s downfall.

Screamersville became the county seat in 1819 and was then known as the “Town of Marengo.” The name changed again in 1823 to “Hohenlinden,” commemorating the battle at Hohenlinden, Bavaria, where the French defeated the armies of both Austria and Bavaria. The spelling was later shortened to Linden.

Old Marengo County Courthouse

After Marengo became a county, the first building to serve as a courthouse was a simple one-room log cabin. To meet the needs of the county, a larger two-story structure was constructed in 1827 on Cahaba Avenue which was Linden’s business district at the time. After the building burned in 1848, a third structure was constructed in 1850 on the site of the former courthouse.

This new building was designed by the architecture firm Town & Davis and was a similar plan to one of the similar previous designs, the West Presbyterian Church in New York. According to the National Register of Historic Places, “The front elevation is plaster over brick and the remainder of the exterior is, brick. A pedimented facade portico features two Doric columns in antis, flanked by corner pilastered sections. The entablature which encircles the building is adorned with a row of dentils, and a projecting cornice.

A second-story balcony within the recessed portico links the columns to each other and the walls. Stairs at either end of the recessed portico lead onto this balcony.

There are three entrances on the ground floor beneath the balcony. The wooden doors on either end lead into large rooms and the central door leads into a hallway. On the second story, there are two wooden double doors leading into the auditorium from each end at the head of the stairs.

The gabled roof is covered with tin and there are two end-interior chimneys on either side of the building. There are 18 double-hung windows, nine on either side. The upper floor has five windows to the side with the, later addition of stained glass in the upper sashes. Flat rectangular stucco lintels top the windows. The lower floor has four windows and one door on each side. Windows are similar to the upper story windows but lack the stained glass in the upper sash. The doors located in the center of each side are wooden with rectangular horizontal panels.“

The new building would serve as the courthouse continuously, except for a brief period during Federal Reconstruction when the county seat was moved to Demopolis, until 1902. The courthouse was also the site of a notable event on October 9, 1890, when Alabama’s most infamous and notorious outlaw, Rube Burrow, was shot and killed in the street in front of the building, an event that locals still talk about to this day.

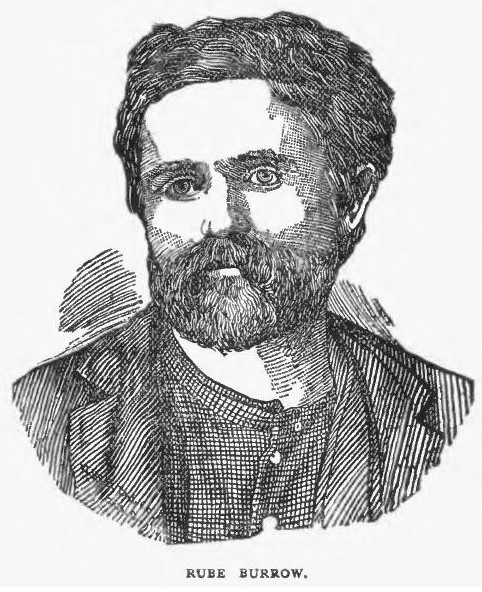

Rube Burrow, Old West Outlaw

Reuben Houston “Rube” Burrow, often spelled Burrows, was a train robber and outlaw in the Southern and Southwestern United States. In just a few short years, Rube Burrow and his gang became one of the most infamous and hunted men in the Old West since Jesse James. From 1886 to 1890, the Burrow Gang robbed express trains in Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana, the Indian Territory, and Texas while being pursued by hundreds of lawmen including the Pinkerton National Detective Agency.

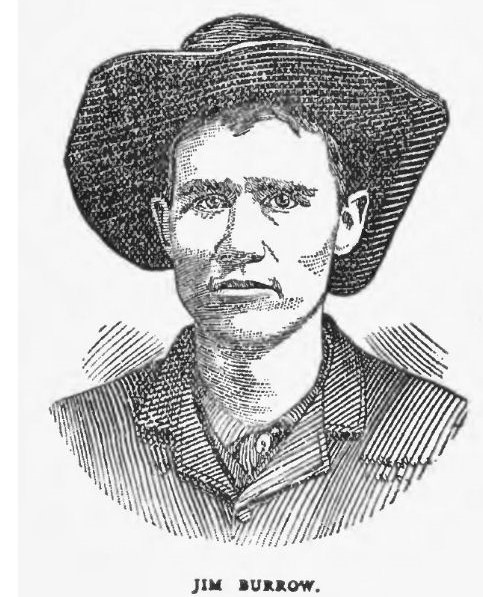

Rube Burrow was born on December 11, 1855, in Sulligent, Alabama, the son of Civil War veteran Allen Henry and Martha Caroline Terry Burrow. Rube Burrow worked on the family farm in Alabama until the age of 18 when he moved to Stephenville, Texas to work on his uncle’s ranch. By all accounts, Burrow intended on being a rancher by saving enough money to buy a farm, marry, and start a family of his own. His wife though, Virginia Catherine Alverson Burrow, died of yellow fever in 1881, leaving him to care for their two children. He remarried in 1884, moved to Alexander, Texas, and tried his hand at farming but after the crops failed, he joined his brother Jim Burrow in robbing trains.

Rube’s First Train Robbery

On December 11, 1886, Rube and his brother Jim teamed up with William L. Brock, Henderson Brumley, and Nep Thornton to rob the Denver & Fort Worth Express while returning from a trip to the Indian Territory. Burrow and the other men waited at the train depot in Bellevue, Texas until the train arrived. They drew their guns at the crew and entered the train.

In the smoking car were U.S. Army Sergeant Charles Connor and three guards of the 24th Infantry Regiment, one of the Buffalo Soldier regiments. The troops were escorting two deserters, George Rich and Frederick Bulz, to the military prison in Fort Leavenworth, Kentucky. When they found out that the train was being robbed, the guards drew their guns and readied themselves for a fight.

Before the outlaws reached the first coach though, Henery Entlegger, a passenger traveling from Fort, Oklahoma, came into the car the troops were staying in and asked that no resistance be made. He stated that the passengers had already hidden away their valuables. He also feared that there could be a dozen or more outlaws hiding in the ravines on either side of the train. Acting on his suggestion, the troops sat back down in their seats and allowed the robbers to relieve them of their arms. According to Fort Worth Daily Gazette, the men took with them $103.60, three gold watches, six silver watches, five pistols, and a gold ring.

Rising Infamy

On June 9, 1887, Burrow and his gang boarded the Texas & Pacific Express heading eastbound from Benbrook, Texas. Learning from their mistakes from the last holdup, Burrow had engineer John Baker held at gunpoint and forced him to stop the train on a trestle over Mary’s Creek just outside the town. This was meant to discourage passengers, who would have to “brave the heights and meager footing” in order to interfere with the robbery. The gang came away with $1,350.

As news of the robbery reached Fort Worth, a posse of eight men and Sheriff Benjamin H. Shipp drove out to the scene. The posse was heavily armed and brought along three bloodhounds with them. A little later, a larger group of lawmen under City Marshall Samuel Farmer went out on horseback hoping to cut the outlaws off. About fifty men scoured the area and while the hounds were able to find their scent, the trail ended at the creek as the gang likely waded through the creek to escape. Despite the manhunt, the Burrow Gang robbed another train in the same spot on September 20, 1887. On the second occasion, news reports estimated the robbers netted themselves between anywhere $1,200 to $30,000.

On December 9, 1887, the Burrow Gang stopped a St. Louis, Arkansas & Texas Railroad train in Genoa, Arkansas. The train was guarded by an agent of the Southern Express Company, and when he heard gunfire outside, he blew out his light and hunkered down. The outlaws demanded that he open the train. When the agent refused, Rube Burrow ordered the train’s engineer to douse the car in oil, fully intending to set the train on fire. Before Burrow could implement his plan, the agent gave in and opened the train for them. The Burrow gag escaped with a Louisiana lottery payoff estimated to be between $10,000 and $40,000. The robbery would lead to the gang’s downfall.

Most Wanted

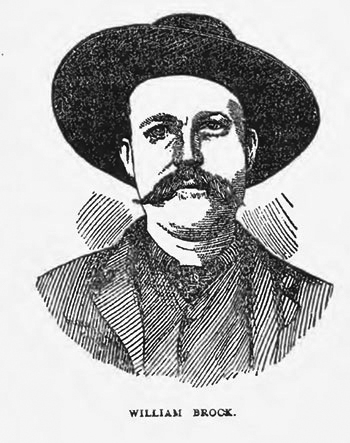

The Southern Express Company did not take the loss lightly and called up Pinkerton National Detective Agency, the same agency hired to track western outlaws Jesse James, the Reno Gang, and the Butch Cassidy’s Wild Bunch, including the Sundance Kid. Within five days, Pinkerton men came up with their first major lead. A deputy sheriffed encountered three suspicious-looking men on the day of the robbery who left behind a raincoat which was eventually traced to a store in Dublin, Texas. The sales clerk identified the man who bought the coat as William L. Brock. Brock was arrested and confessed to participating in the robbery and gave up the names Rube and Jim Burrow.

Having no criminal record, the Burrows were unknown to the authorities and Brock insisted that he did not know their whereabouts. The Pinkertons got their second break when Brock received a letter from the Burrow Gang’s leader. Rube Burrow had no idea that Brock was in custody. According to the return address, the letter was sent from Lamar County, Alabama and a posse was organized by Sheriff Jasper Pennington and sent to his brother’s homestead. Jim spotted them approaching the house and ran for the woods towards his father’s house where Rube was lying low. Before the posse could arrive, the two brothers escaped without being seen and headed toward Montgomery.

Wanted Dead or Alive

Two weeks later, the Burrow brothers’ actions aroused suspicion aboard a Louisville & Nashville train in southern Alabama and the conductor telegraphed ahead to the Chief of Police in Montgomery. Upon their arrival, it was raining hard. As the two stepped off the train, they were approached by a dozen men wearing raincoats. Rube immediately knew who the men were. Although he was well-armed, his brother Jim didn’t even have a knife on him. Rube, therefore, waited for a better opportunity to make a getaway.

Surrounded by police, the two men walked silently to the police station. After a few blocks, Rube signaled to Jim and the outlaws made a break for freedom. The policemen opened fire and Rube returned fire as he ran. Jim fell wounded but Rube, who was said to “run like a deer,” escaped. Neil Broy, a printer who attempted to stop Rube received a bullet to his chest.

Rube hid out on the outskirts of the city and spent the night in a “negro’s cabin.” Suspecting he was harboring a wanted outlaw, the man sent a messenger to the city to notify the Chief of Police. The next morning, heavily armed policemen surrounded the cabin ready to capture or kill Burrow. The man who owned the cabin reportedly told Burrow, “Boss, dere’s some white men out here dat wants to see you.” Burrow replied, “Well, they can’t do that.”

Burrow peered out the door only to be welcomed by a volley of bullets. He removed his shoes, hung them over his shoulders, and with a pistol in each hand made a break through the back door into the swamp. Just as he entered the swamp, he got hit with a load of birdshot in the back of his neck. The posse gave up the chase not daring to enter the swamp. Rube later found a country doctor who removed the pellets from his neck. His brother Jim Burrow was taken into custody and jailed in Texarkana where he would die in prison of tuberculosis on October 5, 1888, before he could stand trial.

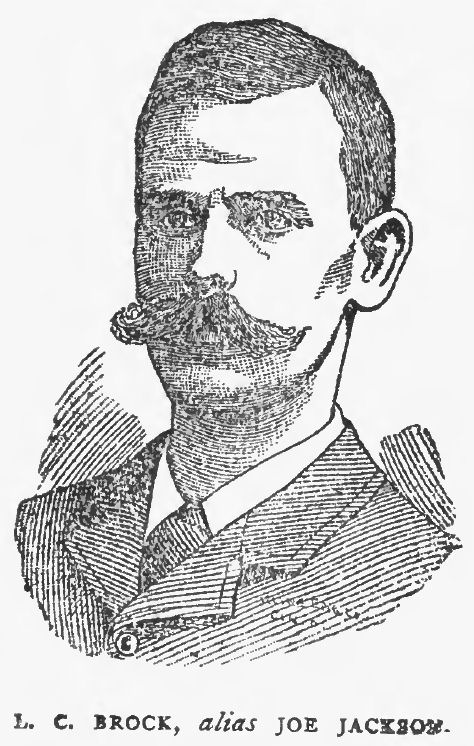

L. C. “Joe Jackson” Brock

After his escape from Montgomery, Burrow and his accomplice Leonard Calvert Brock, no relation to William L. Brock, robbed an Illinois Central express train at Duck Hill, Mississippi. Leonard Calvert Brock, better known as Joe Jackson, was born in Coffee County, Alabama on July 13, 1860, to Joseph E. and Sallie F. Harrell Brock. Although his father was a physician, Brock was raised on a farm and had limited schooling.

Brock went to Texas in 1886 after stabbing a black man in Alabama. He drifted around the state often working with cattle or in the lumber industry although, by some accounts, Jackson was said to have been the only member of Sam Bass’ gang to survive the shootout at Round Rock in 1878. He first met Rube Burrow in the spring of 1886 when he worked with him driving cattle to Fort Worth. He drifted around for a couple more years before joining Burrow in December 1888.

On December 15, 1888, the outlaws boarded the Illinois Central express train when the conductor reported a robbery was in progress. Two passengers—Chester Hughes with a Winchester rifle and John Wilkenson with a revolver—rushed to the express car to apprehend Burrow and Jackson. In his posthumous confession, Jackson admitted to firing a shot into Hudges’ heart, killing him. Following the robbery, Rube and Jackson returned to Lamar County, Alabama, and remained there for several months. During his stay in Lamar County, Rube Burrow committed was many believed was “the most brutal and inexcusable murder of his career.”

The killing of Postmaster Moses Graves

In July 1889, Rube ordered a false beard to disguise himself and had it sent to W. W. Cain at the post office in the small community of Jewell, Alabama. Two weeks later, he sent his brother-in-law, Jim Cash, to retrieve the package for him. Cash was informed by Postmaster Moses Graves that the package was there, but it needed to be signed by W. W. Cain. Cash left and told Rube the situation.

That same evening, three men were handling packages behind the counter of the post office when they came upon Rube’s package, asking, “Who’s W. W. Cain?” Graves replied, “I don’t know but Jim Cash came here today and wanted that package.” They opened the package and found a false beard inside. Since Jim Cash had a full beard, the men figured it must’ve been for Rube Burrow. They confronted Cash about it only for Cash to deny it was for Burrow. Following the encounter, Cash gave a full account to Rube of what had happened.

The next morning, “a tall, muscular fellow on horseback” stopped at the post office and asked if there was a package for W. W. Cain. Graves replied, “Yes, it’s here.” Rube drew his pistol and fired two shots into Graves’ chest. He leveled the pistol at Graves’ wife and compelled her to hand him the package. He tipped his hat at the woman, mounted his horse, and rode off. Due to the uncharacteristically cold-blooded murder, the local residents who viewed Rube Burrow as a sort of folk hero turned against him and forced him to flee the county.

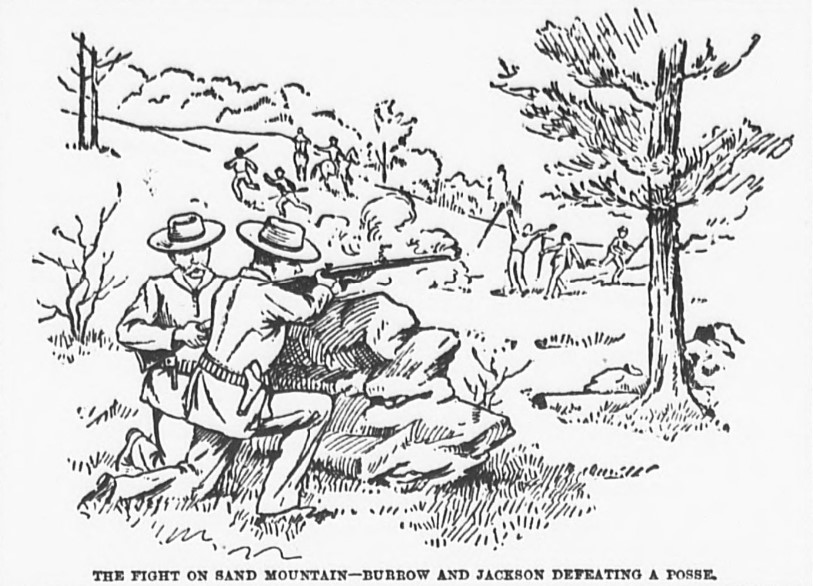

The Battle at Sand Mountain

The Burrow Gang continued robbing trains despite being wanted fugitives and being reduced to just two men. On September 25, 1889, Burrow, Jackson, and a new accomplice, Rube Smith, robbed the Mobile & Ohio express train near Buckatunna, Mississippi, and then the Northwestern Railroad train in Louisiana two months later. Pinkerton detectives were able to track the outlaws to the mountains of Blount County, Alabama where Burrow and Jackson were staying in a cabin owned by an old man named Ashworth. The detectives notified the county sheriff and returned with a small posse. As the lawmen approached the cabin, Rube took one of the women of the house hostage, wrapping an arm around her and using her as a shield. After sharing a few shots with the lawmen, the outlaws fled into the woods.

The sheriff returned the next morning with a posse of fifty men and found the outlaws not far from the cabin, resting in a clump of trees in the center of a field at the foot of Sand Mountain, a sandstone plateau located in northeastern Alabama on the southern tip of the Appalachian Mountains. Burrow and Jackson kept behind some large rocks until the posse was within two hundred yards. Up until now, the Burrow Gang had only been involved in small skirmishes and brief gunfights with very few losses, but this battle would prove just how experienced and dangerous these outlaws were.

Rube jumped out from behind a rock and took a quick but deliberate aim, and sent a ball into the forehead of a young farmer who volunteered on the manhunt. The posse responded with a hail of bullets without a single shot hitting its mark. Jackson fired back and clipped the right ear of one of the posse, and Ben Woodward of the posse fell with a bullet through his heart. Then a third, fourth, and fifth man fell in rapid succession. The sheriff rushed into cover, frightened of how accurate and fatal the outlaws’ shots were. The posse was demoralized and allowed Burrow and Jackson to escape.

The End of the Burrow Gang

In late 1889, Burrow and Jackson separated, agreeing to rendezvous later. After evading capture for nearly six months, Jackson was spotted on a train in Columbus, Mississippi, and arrested. Accomplice Rube Smith was soon captured and was sentenced to 10 years in the Mississippi State Penitentiary for the 1889 Buckatunna robbery, but was then tried again in Federal court. He was found guilty of mail robbery and sentenced to life imprisonment in the Ohio State Penitentiary in January 1891 as inmate #21,849 and died on April 20, 1895.

Joe Jackson though knew he would be sentenced to death for the countless murders he’d committed. In December 1890, while he and Smith were being moved to trial, Jackson bolted and ran up to the highest point he could reach of the penitentiary. Two officials brought a mattress out hoping to catch him if he were to jump while others sought to reason with him. This lasted about an hour before he shouted out his real name and said, “I would make a statement if there was a reporter here,” and jumped, dashing his brains against the brick floor.

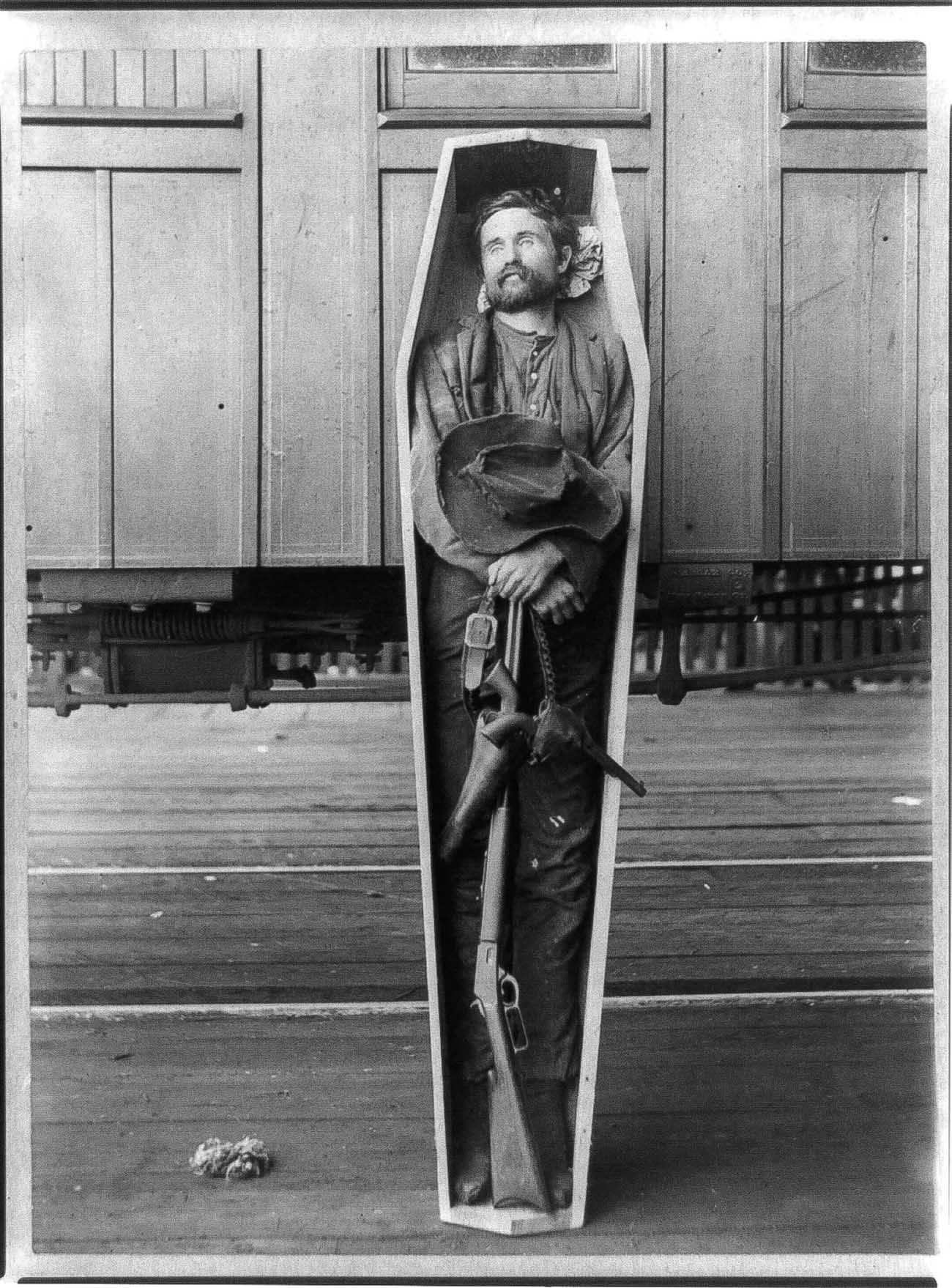

Earlier that year on September 1, 1890, Rube Burrow boarded a Louisville & Nashville Railway train in Flomaton, Alabama. Just as he had done in Benbrook, he held the engineer at gunpoint and ordered that he stop the train on a bridge over the Escambia River in northern Florida. He ordered the engineer to break down the door of the express car with a coal pick and came away with just $256.19. This would be the tenth and last train robbery committed by the (now one-man) Burrow Gang.

Detectives were able to track Burrow from Florida back to Alabama. Thanks to two men, John McDuffie and Jefferson Davis “Dixie” Carter, detectives captured Burrow on October 7, 1890, in a small cabin in Myrtlewood, Marengo County, Alabama.

The following day, Rube Burrow, now in a jail cell at the Marengo County Courthouse in Linden, complained of being hungry. He asked John McDuffie, who was guarding him, to hand him his saddlebags which he said contained some crackers. What the bags also contained were two pistols. Now armed, Burrow locked McDuffie in the cell and left to find Jefferson Carter, who was holding the Louisville & Nashville Railway robbery money and the sixteen-round Marlin rifle that had been taken from Burrow upon his capture. Burrow found Carter at the general store across the street and the two men exchanged gunfire. When the shooting ended, Carter was wounded and Rube Burrow lay dead in the street.

Rube Burrow’s body was shipped back to Lamar County by train, making a stop in Birmingham where hundreds viewed the corpse and snatched buttons from his coat and cut hair from his head as souvenirs. Burrow’s father met the train in Sulligent. Reportedly, the train attendants threw the coffin at his feet and said “It is Rube.” Rube Burrow’s body was carried back to his home community near Vernon and buried in Fellowship Cemetery. Something interesting to note, his gravestone reads, “Rube Burrows,” a small misspelling of his last time due to its often use by newspapers.

Old Marengo County Courthouse Abandonment

In 1902, the county commissioners decided that a much larger courthouse was needed. They also decided that a better location would better serve the community as the business district had moved to the southeast along South Main Street. A new three-story Richardsonian Romanesque-style courthouse designed by architect Frank Lockwood with a five-story clock tower. It was built at the corner of North Main Street and East Coats Avenue at the site where the current courthouse now stands, leaving the old courthouse for use as a public school. The building was used for various other reasons such as a skating rink, horse stable, dance hall, and National Guard Armory.

In 1915, the building was sold for $500 to the Ladies Aid and Women’s Missionary Society of Linden Baptist Church for use as a church. The building was used by the church for services until January 1, 1947. On July 18, 1947, the Linden Baptist Church and Women’s Missionary Society of the Women’s Missionary Union of the Linden Baptist Church sold the property to the American Legion and Veterans of Foreign Wars. The second floor was used as a youth center between 1964 and 1969. The American Legion occupied the building until 1973.

The following year, the Old Marengo County Courthouse was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The building was also documented on June 13, 1935, by photographer Alex Bush as part of the Historic American Buildings Survey. The building is currently owned by the Marengo County Society which has attempted to renovate the structure at some point. Since the American Legion vacated the building in 1973, the building has sat largely empty and unused.

Photo Gallery

References

Fort Worth Daily Gazette; Library of Congress. (December 12, 1886). HOLD UP YOUR HANDS! Robbers Go Through the Passengers of a Fort Worth & Denver Train Near Bellvue

The Salt Lake Herald. (December 4, 1890). HIS SKULL WAS CRUSHED. Sensational Suicide of a Train Robber in Prison

Hometown by Handlebar. (May 4, 2013). Double Trouble: The Burrow Gang and the Train Twice-Robbed (Part 2)

The Sun; Library of Congress. (October 12, 1890). RUBE BURROW, OUTLAW. The Career of a Desperate and Reckless Train Robber

Legends of America. (retrieved October 20, 2022). Leonard Brock—Burrow Gang Member

National Register of Historic Places. (January 18, 1974). Old Courthouse