| City/Town: • Summerfield |

| Location Class: • Educational • Religious |

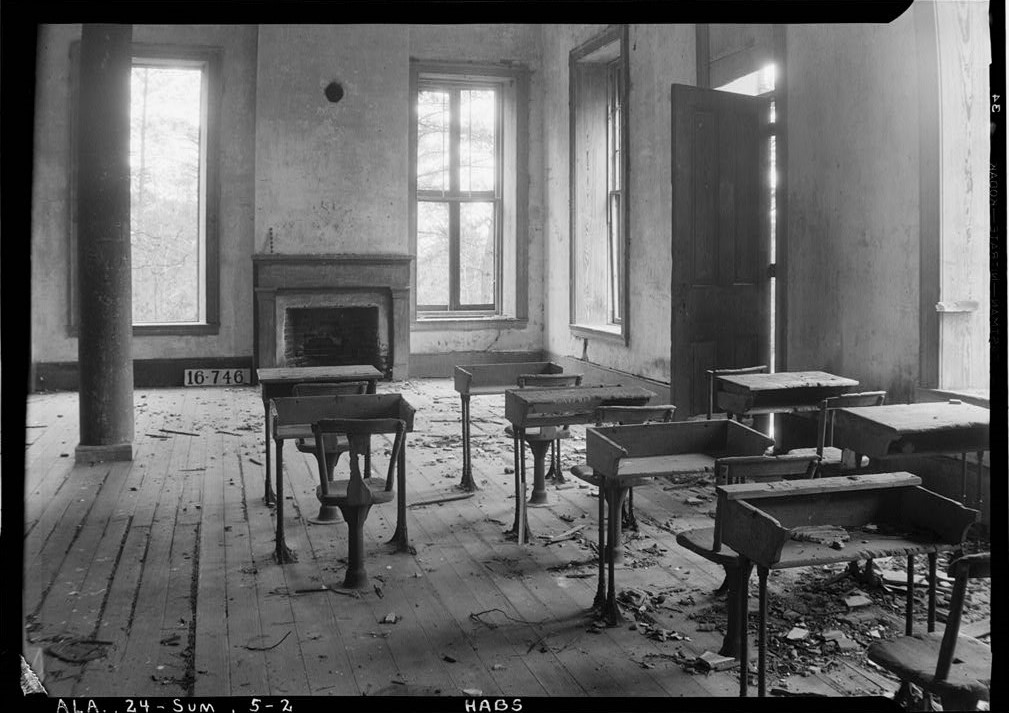

| Built: • 1842 | Abandoned: • 1919 |

| Status: • Burned Down |

| Photojournalist: • W. N. Manning |

Table of Contents

Centenary Institute. Summerfield, Ala.

Deep in the heart of Alabama, an hour and a half south of Birmingham lies the unincorporated community of Summerfield. Formerly known as Valley Creek, this small town is home to an institution that was renowned throughout the state over one hundred and fifty years ago. The Centenary Institute was established in 1842, three years after the centenary of worldwide Wesleyan Methodism was celebrated in Selma, Alabama.

Although it was a boys and girls school, the different genders were kept strictly separated. The buildings their classes were in were separate, divided by a beautiful valley. Their curriculums were separate and not to be heard on campus by the other gender. They sat separately at school functions and remained separate at public functions like church and Sunday school. The only observed holidays were Christmas and the Sabbath day. Alcohol, jewelry wearing, and attending “any unlawful and expensive amusement” were forbidden while school was in session.

The building project began with the citizens of Valley Creek, Alabama in Dallas County donating $9,000 to fund the incipiency of the Institute, as well as other items and gifts, which ended up being the largest donation made by any of the other churches in the conference. This led to the Institute being located in Valley Creek. The Centenary Institute also ended up absorbing The Valley Creek Academy, only 13 years after the Academy had been chartered by Methodists. The new Centenary Institute would have covered a large area and had a library as well as a designated area for music, concerts, and recitations which would’ve been performed by the students.

Before it opened to the public, Benjamin Inhabit Harrison, M. A. served as the head of the school, due to his standing as a prominent member of the community. In December of 1841, Harrison began communication with Rev. Archelus Hughes Mitchell in order to secure Mitchell as the president of the school for the upcoming opening in 1842. In June of 1842, Mitchell accepted the position and began his employment at the Institute.

In 1845, the town of Valley Creek was urged to change its name to Summerfield by the Centenary Institute’s board of trustees. This was intended to increase the popularity of the town and therefore the school by not implying that the town was located in a lowland area, which at the time was thought to increase sickness. Mrs. A. H. Mitchell and another former missionary woman involved with the school were the ones who suggested the name Summerfield in honor of a notable and eloquent Methodist preacher named John Summerfield who had died at a very young age.

Rev. A. H. Mitchell, Long-standing Supporter of the School

As President of the school, Mitchell was an inspiring leader. He studied at Franklin College and taught at Emory University, and this education showed in how he structured and ran the school. From its opening in 1842 to 1845, the first year with a graduating class, the Centenary Institute’s yearly attendance nearly tripled from 60 students to 165 students. At its peak, the enrollment was around 200 students a year, which is comparable to the entire present-day population of Summerfield. Under Mitchell’s oversight, the school continued to improve until 1851 when he resigned in order to devote more time to the holy calling of the ministry.

While the attendance and enrollment of the school continued to improve after his resignation, the funding for the school began to lose traction and the board tried to acquire reverends Richard Henderson Rivers and A. R. Holcombe to overtake the roles of presidents of the boys and girls buildings, but since the school was offering these positions on a self-supporting basis, they were unsuccessful at finding someone to replace Mitchell right away.

This led to Mitchell continuing his involvement with the school by organizing yearly scholarships, sold for $30 or $400, which covered classes of specified curriculum or any class offered by the school, respectively. Eventually, the price of the unlimited scholarship was lowered to $80 since financial hardship was becoming more prevalent. There was even more effort to borrow money from the Conference, and it is recorded that a donation of $7,000 was secured for the school on the condition that it would be paid to the beneficiaries of the school. Given along with this was the gift of a vacant lot for a new building for the school, but after these donations were made, money was so scarce with the people of the community that nobody had anything to spare to fund the institute.

In 1850, the board of the school declared that minimal clothing, jewelry, and entertainment were to be worn and had by the students, as large bills had been accrued by the school due to students shopping for “extravagant” clothes at the local stores. By 1852, the school had transitioned to a fully self-funded institute and could not afford the large bills they received for these extravagant clothes from the local merchants. By 1856, only propositions for more funds were seen, and no follow-up action. Since Mitchell would no longer be returning to head the school, job ads for a new head were put up but got no interest. Because of this, Mitchell remained at the school until 1857, overseeing the girls’ side of the establishment during which time the school’s buildings were insured.

The Institute continued to decline and was eventually converted to a non-religious school after Vaughn left his position. A few years later, the school was merged into a public school. As the Alabama Conference owned the buildings of the former Centenary Institute, the institution was converted into a home for the Alabama Methodist Orphanage. During this time, Mitchell would return to the school when it was converted to an orphanage—an institution that he became heavily involved in and was extremely passionate about. Towards the end of the Institute’s life, he oversaw the construction of a new fence surrounding the property. This would actually lead to his death, he caught a severe cold while supervising this build and never recovered, leading to his death at 95 years old on October 3, 1903.

Other Centenary Institute Presidents

The Centenary Institute did hire other principals to run the school after Mitchell’s professional departure. All of these principals were notable men of the Alabama education community who either had or would go on to have experience teaching at other notable schools in the area including the University of Alabama and Vanderbilt University. They all had religious backgrounds and were well-versed in the ideology of Methodism. The Centenary Institute was a very renowned school at the time and it can be presumed that this, paired with the school’s financial crisis and struggles from the war, would have driven these notable men to be attracted to the experience as educators at the institute before leaving for newer, more financially stable, or more recognized schools.

Following Mitchell’s departure, Reverend W. A. Montgomery served as president of the Centenary Institute followed by Reverend Richard Henderson Rivers in 1861. Rivers was described as one of the old oldest and most distinguished ministers of the Southern Methodist Episcopal Church. He graduated from LaGrange College in Georgia where he was appointed a professor by Bishop Soule. He next went to the Athens Female Institute in Alabama where he remained for three years.

He helped build the Centenary College in Jackson, Louisiana, and was appointed its President. After his time at the Centenary Institute in Summerfield, he took charge of the Logan Female College in Russellville, Kentucky before establishing the Martin Female College in Pulaski, Tennessee in 1870. He continued his work in Alabama taking charge of female colleges in Auburn, Eufaula, and Greenville, before moving to Kentucky.

During the war, the already struggling school lost even more money, which continued to contribute to its downfall. Robert Kennon Hargrove took over the position immediately after the war in 1865 until 1867 when Dr. William James Vaughn relieved him until 1872. In the last year of Hargrove’s presidency, the school saw only three graduates and the decline continued. After Vaughn left the Centenary Institute, he became employed by Vanderbilt University, whose chancellor recruited him to teach as Vaughn was a past student of his. Reverend A. D. McVoy took charge following Vaughn’s departure and remained in that position for a few years.

Closure, Reuse, and Abandonment

Years later, the Alabama Conference converted the Centenary Institute into a home for the Alabama Methodist Orphanage. In 1910, the orphanage was moved to Selma and much of the campus of the former Centenary Institute was abandoned. That same year, Reverend J. M. Batte opened the Selma-Summerfield College. just like the institutions before it, the college struggled financially throughout the decade it was operational. In March 1916, it was reported in local newspapers that Charles H. “Chuck” Garrett, the self-described “world’s greatest long-distance walker,” was a guest at the college for several days and gifted a check to Batte for $18,000. It’s unknown if Batte cashed the check or if the check when even legitimate, but regardless, the property was foreclosed on May 2, 1919.

W. N. Manning, a photographer for the Historic American Buildings Survey, documented the remaining buildings in March 1934 which were very much in ruins by this time. That same year, The Selma Times-Journal published a series of articles written by P. M. Munro, Superintendant of City Schools for Dallas County. In his writings, Munro details how the school came about, its impact on the community, and the reasons that led to its closure.

The Storied Landmark Burns

On the evening of March 16, 1935, T. G. Kenan, the owner of the property, called up the Selma Fire Department to report a fire at the abandoned school. Three firemen were sent to the scene but since there was a lack of running water, no trucks were sent to fight the fire. These three firemen utilized fire extinguishers instead which were brought to the scene in automobiles. Due to the slow response time, the lack of equipment, and the high winds that evening, the old Centenary Institute was quickly destroyed by the flames. According to a report in The Selma Times-Journal, the building was occupied at the time by “a lone negro tenant, serving as caretaker.” It was also said that this loss was the second landmark destroyed in a short period of time as the Kirkpatrick House in Cahaba had burned down just a few weeks prior.

Legacy

Regarding the quality of the school, while it was actively serving the community, Rev. Anson West says that if the city of Summerfield had grown comparable to Macon, the Centenary Institute would have “shared honors with Wesleyan College”, the “first chartered college to confer a degree upon women.” Dr. John Massey also spoke highly of the school, calling it “the most notable institution in all central Alabama.” Massey was a well-known educator in the community at the time, so this remark was very complimentary. Another notable man of the community, a Methodist preacher named Abiezer Clarke Ramsey, sent all of his children and one of his stepdaughters to the Centenary Institute.

By all of these accounts, the values, obedience, religiousness, and skills taught at the school were high quality and produced well-equipped members of society, despite the actual curriculum being a bit sub-par. Since the main focus of the Institute was religious, however, the school remained prominent in the community, relying on producing good people and not focusing on esteemed academics as much as other colleges. Despite the financial challenges the school faced in the late forties, evidence of enriching years from the fifties onward was found via diaries from people involved with the school and students who attended, old school newspapers, and records of events. Overall, the Centenary Institute was an influential part of central Alabama’s history for generations.

References

National Register of Historic Places. (January 1982). Summerfield District Nomination Form

The Selma Times-Journal; P M. Munro. (March 25, 1934 p. 7). Sketch of Old Centenary Institute At Summerfield Prepared by Munro

The Selma Times-Journal; P. M. Munro. (April 29, 1934 p. 12). Sketch of Old Centenary Institute At Summerfield Prepared by Munro

The Selma Times-Journal; P. M. Munro. (May 13, 1934 p. 5). Sketch of Old Centenary Institute At Summerfield Prepared by Munro

Neale Publishing Company; Isabella Margaret Elizabeth Blandin. (1909 p. 87-89). History of Higher Education of Women in the South Prior to 1860

The Selma Times-Journal. (May 17, 1935). OLD CENETERNARY COLLEGE BURNS LATE SATURDAY