| City/Town: • Birmingham |

| Location Class: • Commercial |

| Built: • 1906 | Abandoned: • 2002 |

| Historic Designation: • National Register of Historic Places (1985) |

| Status: • Abandoned |

| Photojournalist: • David Bulit |

Table of Contents

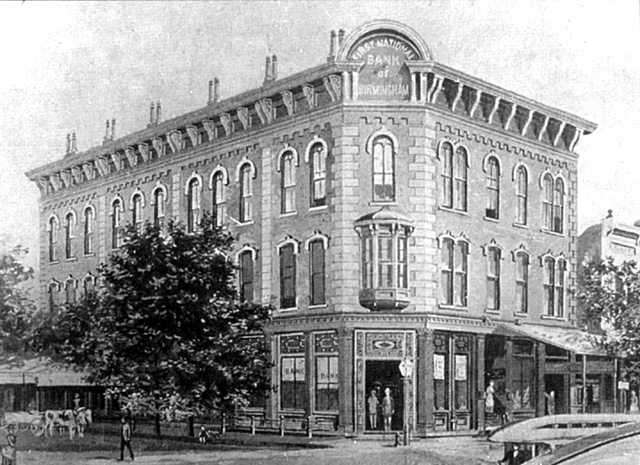

National Bank of Birmingham

The Brown Marx Building sits on the site of the original National Bank of Birmingham, the first bank in the state to be chartered under the National Bank Act in 1872. The bank building was a three-story brick building constructed between 1872 and 1873 for Charles Linn’s National Bank of Birmingham. It was the first multi-story commercial building to be built in Birmingham and also housed a large ballroom called Linn Hall. Because the $36,000 structure was erected in the midst of a national economic depression and a cholera outbreak, it became known as “Linn’s Folly.”

1873 Cholera Epidemic

In June 1873, the cholera epidemic made its way down from Huntsville to Birmingham through soiled bed linens. The first patient died within three days of becoming ill. The next patients were two young sisters who had visited the first patient’s home. They also died quickly, with their effects discarded carelessly into the marshy waters behind their house, which fed into a basin on the edge of the “Baconsides” from which residents obtained their drinking water. The city took no effort to clean the streets and alleys, to drain and disinfect cesspools and wet places, nor had cleanliness been demanded in privies and stables until July 1, when cholera was declared an epidemic in the city.

The illness spread rapidly through the rest of Birmingham with city leaders ordering that the town bell, which had rung for deaths, no longer be used as its tolling was too frequent and too distressing. About half of Birmingham’s 4,000 residents fled the city out of fear of death. Fortunately, as quickly as the disease entered the city, it had left. By the end of July, there were no reported deaths or cases of cholera.

1873 Economic Depression

During this period, the nation was also amid a financial crisis. On 9 May 1873, the Vienna Stock Exchange crashed. Investors began to sell off the investments they had in American projects, particularly railroads. Europeans began selling their railroad bonds, and soon there were more bonds in supply than were demanded. Railroad companies could no longer find anyone who would lend them cash with many railroads going bankrupt.

One of the biggest banks in New York City, Jay Cooke & Company, had invested heavily in railroads, and as the railroads went bankrupt, so did Jay Cooke & Company. The closure of such a large bank triggered bank runs throughout North America, which began a nearly five-year-long economic depression.

Ignoring the evident risks involved, Linn persevered in bringing his three-story brick bank building to its completion. This endeavor, the tallest and most magnificent structure ever erected in the city, earned the dubious moniker of “Linn’s Folly” from doubters who had advised him to cut his losses. Undismayed, he saw the building completed in December 1873 and invited 500 guests to an opening-night celebration on New Year’s Eve known as “The Calico Ball.”

The Calico Ball

Linn and his family stood at the front door of the National Bank of Birmingham to welcome guests. Acknowledging the city’s financial troubles, Linn urged many of the ladies and gentlemen in attendance to have their ball gowns and evening suits fabricated from calico.

Linn’s daughter, Lizzie Linn Molton, provided piano music on the first floor as sandwiches and coffee were provided for guests. At 9:00 p.m., the James T. DeJarnette band from Montgomery began playing music for reels, lancers, cotillions, rounds, and other dances in the 2nd floor ballroom. The music stopped at midnight and the presentation of painted panels depicting the passing woes of 1873 and the optimism of the coming year. The dancing resumed and continued until 2:30 a.m. The building, being the center of Birmingham’s commercial district, was later nicknamed “Linn’s Wisdom” and “Linn’s Fame.”

In 1934, Emma Gelders Stern published the novel The Calico Ball which gives a detailed description of the historic event. The Calico Ball is also depicted in Eleanor Bridges’ Cyclorama of Birmingham History, which was designed for the lobby of the Brown Marx Building. The Cyclorama is now part of the Vulcan Park Foundation’s collection.

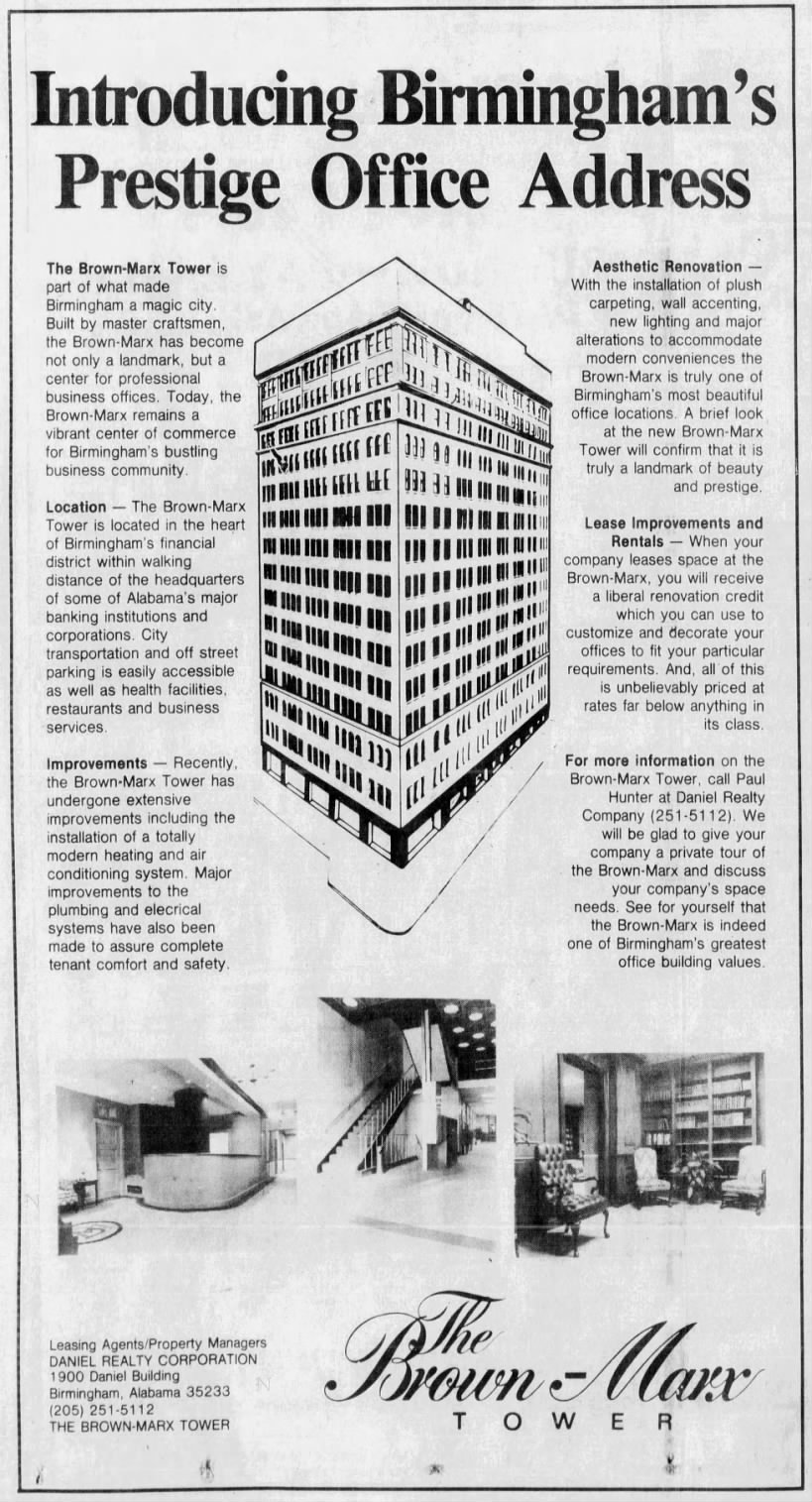

Brown Marx Building

Located on the site of the original National Bank of Birmingham, the Brown Marx Building was named for Otto Marx of Marx & Company and Eugene L. Brown of Brown Brothers & Company, early tenants of the building. Brown Brothers was the largest real estate company in the city and helped raise capital for the development of the First National Bank Building, the Woodward Building, and the Brown Marx Building, for which they also acted as rental agents.

Otto Marx and Eugene L. Brown founded the Eugenotto Construction Company and were responsible for erecting the building. The company announced that the structure would be called the “Eugenotto Building.” The name “Brown Marx Building” was first suggested in the September 21, 1905, issue of the Birmingham Post-Herald. An unknown prominent citizen told the newspaper that the building’s name needed some significance. The Woodward Building was appropriately named after its financier, William Woodward, and the Title Guarantee Building was named after the Title Guarantee, Loan & Trust Company which built it. So why not name the new skyscraper Brown-Marx?

Heaviest Corner on Earth

“The Heaviest Corner on Earth” was a moniker coined in the early 20th century to describe the intersection of 20th Street and 1st Avenue North. This name was bestowed due to the remarkable emergence of four of the southern region’s tallest structures nearby: the Woodward Building (1902), the Brown Marx Building (1906), the Empire Building (1909), and the American Trust and Savings Bank Building (1912).

The announcement about the latter structure’s construction was featured in the January 1911 edition of Jemison Magazine entitled “Birmingham to Have the Heaviest Corner in the South.” Over time, this claim evolved into the improbable title of “Heaviest Corner on Earth,” which remains a popular name for the grouping. In 1985, the “Heaviest Corner on Earth” was added to the National Register of Historic Places. The Brown Marx Building is the only building of the four not to be individually listed.

1908 Expansion

The development quickly became a success, with every floor occupied except for two upper floors. This immediate success encouraged iron magnate William Woodward, who also owned the Woodward Building, to purchase the Brown Marx and more than double its overall size over the next two years. Financed by the financed by the Tennessee Coal Iron and Railroad Company, the expansion created a U-shaped plan, increasing the building’s overall size to 193,000 square feet, 12,000 square feet per floor.

The building has 1,667 windows providing natural light to every office. A four-story Brown Marx annex was constructed just east of the tower facing 1st Avenue. Its ground floor was leased as an independent space while the upper floors connected with the tower.

Architecture

William Weston, a prominent Birmingham architect, designed both phases of the Brown Marx Building. He moved from Chicago to Birmingham in 1901. He immediately submitted the winning design in response to an invited competition for the Woodward Building, which became the first steel-framed building in the city. His other designs included the First National Bank Building (1903), the residence of Otto Marx (1909), the Age-Herald Building (1910), and the towering City Federal Building (1913).

Like many of Birmingham’s early structures, the architects of the Brown Marx building exhibited meticulous attention to aesthetics. The exterior featured intricate banding and arched windows that complemented the light-colored brick facade. Moreover, the ground floor displayed retail merchandise through expansive glass windows set in stone. Alabama marble adorned the interior of the building, and the tower’s pinnacle was adorned with an ornate cornice.

In 1930, when the building was again expanded, the rusticated story was covered over with a more “streamlined” art-deco-inspired light-colored banding. Some interior details, such as Alabama marble and a cornice over third-story arched windows, were later removed in this renovation. The cornice topping the building was removed and replaced by a metal-clad mechanical enclosure at the roofline in the early 1970s.

Tenants

The Subway Cafe

As previously mentioned, the Brown Marx Building was highly successful, with most of it occupied since its opening in 1906. The Subway Cafe opened in the building’s basement on February 20, 1907, a pretentious bar and cafe designed primarily for high-class businessmen.

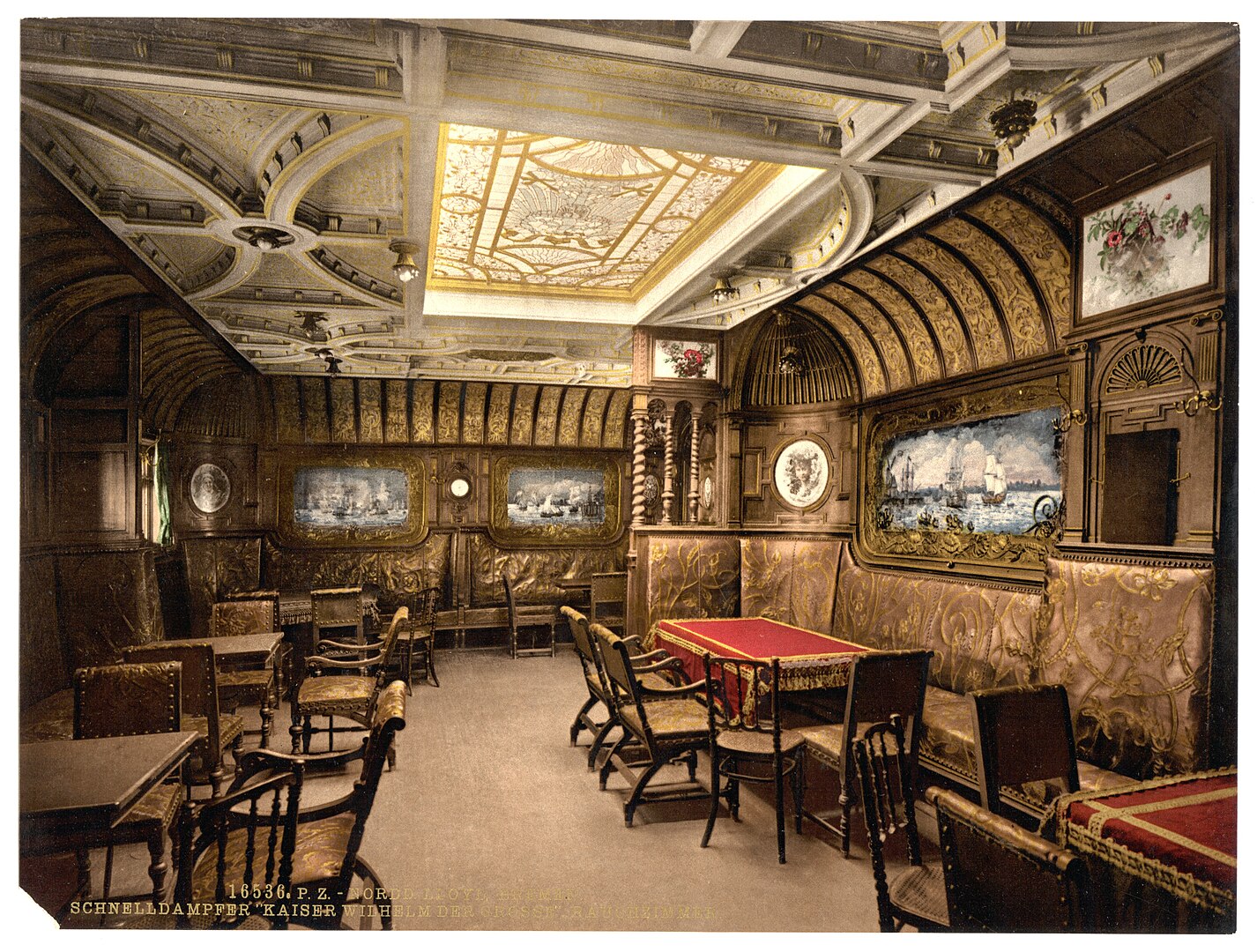

The interior was furnished in Fleming Oak and mission-style furniture. The walls were decorated with landscape paintings and other scenes in inlaid wood, the idea of which was derived from the elegant smoking cabin of the Kaiser Wilhelm der Gross, a German transatlantic ocean liner. Higher up and encircling the bar and cafe were legends appropriate with German, Greek, French, and English. The ceiling was decorated with shields representing the various nations of the world.

Other early tenants include the R. D. Burnett Cigar Company, offices for the Tennessee Coal Iron & Railroad Company and many other railroad companies, various mining companies, attorneys such as Moses Ullman, Samuel Burr, and Sirote, Permutt, Friend, & Friedman, and architects such as Lawrence Whitten, Jack B. Smith, and Henry Sprott Long, the Southern Building Code Congress, and the Raymond J. Horn School of Drafting. Realtor W. A. Watts of the Hillman-Watts Land Company, later renamed Watts Realty, kept offices on the third floor.

The Suicide of Emma C. Blair

On May 28, 1908, Emma C. Blair, a well-known public stenographer, committed suicide by ingesting oxalic acid in her office on the third floor of the Brown Marx. Before her death, she operated a public stenographic bureau with her business partner, J. B. Burkett. The reason for her suicide was her infatuation with a young man who was married to another woman, who gave no encouragement and postponed his wedding due to her worsening behavior.

Upon seeing the marriage license, she called up several of her friends and communicated her intention to them, some of whom contacted the police station. Detective Tom Williams was put on the case and rushed to her office to prevent the act, but he arrived too late.

Upon the discovery of her death, The Birmingham News described the office as a “gruesome scene.” Crowds of the morbidly curious gathered outside the office to learn the details of the tragedy. Blair’s pale body lay outstretched on a small table, her disheveled hair strung across the table in disarray. The pain caused by the strong, caustic chemical left a few lines across her face, but for the most part, a pleasant expression was left on her face as if she had not feared to go.

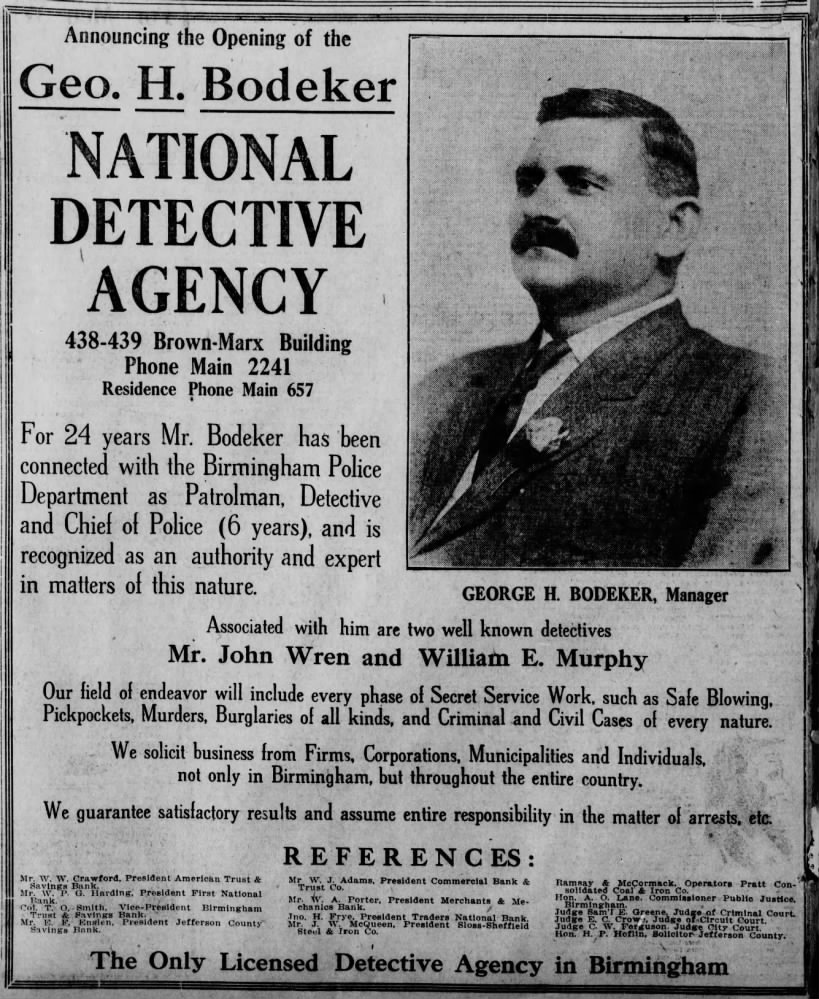

Geo H. Bodeker’s National Detective Agency

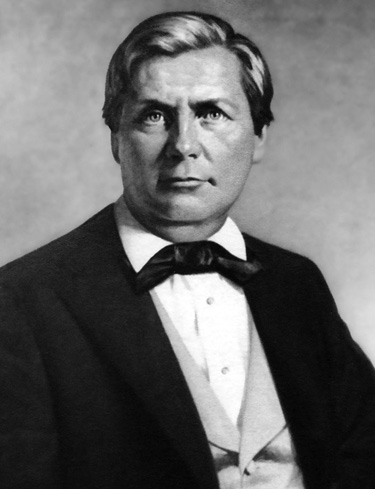

Located on the third floor of the Brown Marx Building was Bodeker’s National Detective Agency, founded by former Chief of the Birmingham Police Department George Henry Bodeker Jr. Bodeker was born May 26, 1865, in Richmond, Virginia, the son of George Henry and Johanna Adeline Bart Bodeker. His German immigrant father served in the Mexican-American War, where he forged a friendship with Jefferson Davis. During the Civil War, Davis appointed him a “Confederate States Detective,” entrusting him with espionage missions behind enemy lines.

Bodeker moved to Birmingham in 1886 and took a job as a streetcar driver before joining the Birmingham Police Department on September 5, 1889. He served for twelve years as a patrolman. He spent a year as a sergeant, then served as warden of the Birmingham City Jail before being promoted to detective under Chief Thomas McDonald. Bodeker was also involved in the arrests of members of the Miller-Duncan Gang, who were responsible for the killing of two Birmingham police officers.

In the 1907 election, Bodeker ran for chief of police and came close to victory, but ultimately lost to William Wier, who claimed that the liquors and sporting interests supported his opponents.

Due to an increase in reports of theft from porches and gardens in July 1908, Bodeker concluded that Black people were responsible and issued an order saying: “There are too many negroes loafing around pool rooms and prowling the streets at night. If you will pick up these rounders for vagrancy there will be less petty stealing.”

Responsible for investigating crimes against people and property, Bodeker also enforced the city’s blue laws, statutes, and ordinances that forbid or regulate entertainment and commercial activities such as the sale of liquor and burlesque shows. Manager E. A. McArdle of the Gayety Theatre circumvented the city’s new ordinance against burlesque entertainment simply by not using that word in his advertising. On January 5, 1909, Bodeker issued a formal warning: “I like to see a good show and enjoy it, but at the same time I will not tolerate any such movements as I saw this afternoon and I assure you that if this occurs tonight, I will most assuredly put the entire troupe under bond.”

Bodeker won re-election in the 1910 election, defeating Thomas Shirley. He publicly supported the former mayor of Birmingham, Alexander Oscar Lane’s calls for regulation of saloons and his statement that “the negro vagrants cause more trouble in a city than all other criminal classes combined.” This came at odds with Bodeker’s correspondence with Booker T. Washington regarding crime, race, and prohibition.

He wrote in part, “…it would be impossible for me to give you the exact figures of crimes committed by the colored people, however, I wish to say that the Prohibition Law as I see it has not benefited the white people or the negroes, as Prohibition is a farce wherever it has been tried. I do not see any difference relative to crimes committed by either race.“

In December 1913, former Chief of Police Conrad Wall Austin, private detective and founder of the Secret Service Agency, charged Bodeker with corruption after it was discovered that during his administration, gambling houses, gamblers, brothels, and “blind tigers” had been allow to operate and were also protected. Austin also charged that Bodeker took bribes from gamblers and prostitutes. At Austin’s recommendation, Commissioner George Ward removed Bodeker from office.

On January 15, 1914, he founded Bodeker’s National Detective Agency, with offices on the second floor of the Brown Marx Building. The agency grew to become the third-largest in the United States, with branches in Charlotte, North Carolina; Chattanooga, Tennessee; Jacksonville, Florida; Montgomery; and Mobile. Bodeker was responsible for breaking up the Lewis-Enis gang of train robbers and capturing train robber Grady Webb and the Harrison gang.

The Suicide of Frank Henry Conner

On February 17, 1914, Frank Henry Conner, President of the General Contractor’s Association, was found dead in his office on the 10th floor of the Brown Marx Building, having shot himself in the head. According to reports, his body was discovered around 8 a.m. that morning when a maid, Lula Map, reached Conner’s office in the course of her work. Frank Conner’s body sat in a chair slumped over his desk in the pool of blood. A revolver was in his hand with the forefinger curled around the trigger. A powder-burned hole above the right ear bore evidence that he held the gun to his temple when he fired the gun.

The maid immediately contacted Eugene L. Brown, who took charge of the situation and contacted the authorities. An investigation of the scene failed to locate any note or letter giving a reason for the suicide. His friends and associates did not understand why he would commit suicide, with most saying he was in good spirits just that morning.

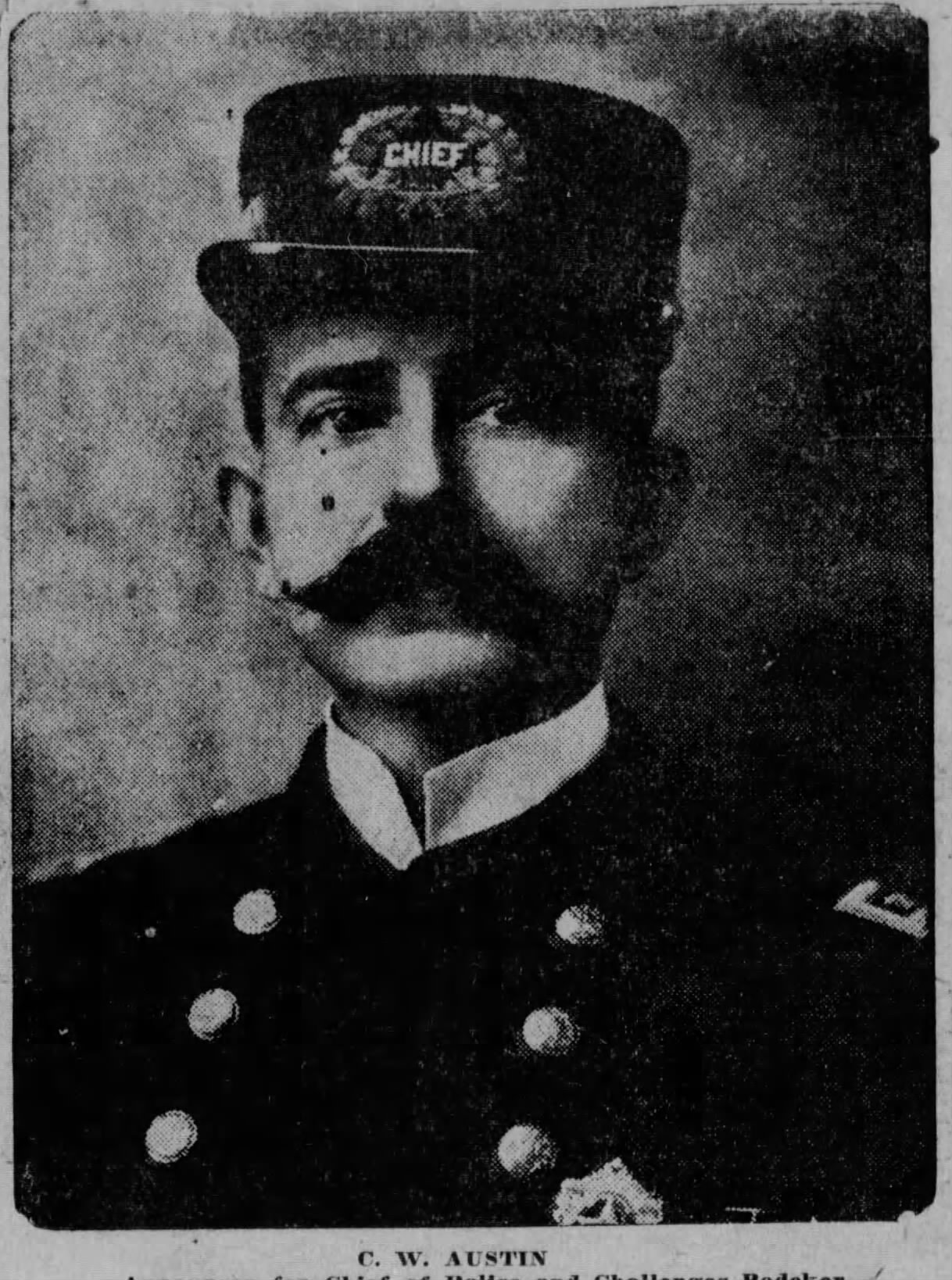

C. W. Austin’s Secret Service Agency

By 1911, C. W. Austin established a private detective agency, C. W. Austin’s Secret Service Agency, operating from offices on the 2nd floor of the Woodward Building. In 1914, leveraging his role as a private detective, he actively participated in probing corruption within the police department. He notably claimed responsibility for removing Chief George Bodeker, alleging suspicions of his involvement in accepting bribes from bordellos and gambling establishments. By 1915, Austin’s agency relocated to the 4th floor of the Brown-Marx Building, just one floor above the recently established Bodeker’s National Detective Agency.

Austin was born in Butler Springs, Butler County, Alabama, on June 20, 1868, the son of Davis Austin, one of Birmingham’s early patrolmen and later the county jailor, with his first wife, Amanda. He graduated from Birmingham High School and followed his father’s footsteps into law enforcement, serving as a deputy under Jefferson County Sheriff Samuel Truss.

Austin left his position in the police force to pursue further education at the Highland Home Institute in Crenshaw County. After six months, he departed and joined Howard College in East Lake but had to discontinue his studies due to deteriorating eyesight. Subsequently, he rejoined the Sheriff’s Department, working under Truss and his successor, Joseph S. Smith. Yet, after another six months, he resigned and ventured into entrepreneurship, opening a saloon at 1720 1st Avenue North.

In 1888, Austin returned to law enforcement, joining the Birmingham Police Department as a private. However, he resigned from this position after two and a half years. Six months later, he returned to duty as a patrolman. By April 1892, he transitioned to the role of constable after being elected, temporarily leaving the department to fulfill his duties. His re-election followed in 1896.

In April 1899, during the municipal election in Birmingham, Austin successfully secured the position of Chief of Police for the City of Birmingham. His victory coincided with Mayor Mel Drennen’s win, who had campaigned on the platform of enforcing Blue Laws rigorously, particularly those mandating business closures on Sundays. Austin commenced his term on May 15th. Subsequently, he was re-elected for a second term in April 1901.

During his tenure as Chief, Austin introduced the Anti-Spitting Law of 1899 and successfully apprehended the notorious Miller-Duncan gang of safe blowers in March 1900. In February 1901, he spearheaded raids on suspected gambling establishments above the Dude Saloon and the Damon & Lee Livery Stable. In the same year, Austin oversaw the department’s relocation to the new Birmingham City Hall, utilizing the expanded facilities to implement a more comprehensive record-keeping system. He implemented the “Bertillon System” for recording the physical characteristics of criminals and enrolled the department in the National Bureau of Identification.

Under his leadership, the Birmingham Police Relief Association was established in response to the tragic deaths of officers J. Wafe Adams and George Kirkley. Austin also played a pivotal role in organizing the State Association of Chiefs of Police and Marshals of Alabama. He advocated for establishing an industrial school for girls during his term.

A biography featured in a promotional book from 1902 proudly proclaimed Austin’s achievements, stating that he had effectively subdued criminal activities originating from other cities and dissuaded a significant portion of that demographic from conducting their illicit operations in Birmingham and the surrounding district.

Following his departure from office, Austin assumed management of the Commercial Detective Bureau, operating from offices located on the fifth floor of the Jefferson County Bank Building. Around 1915, Austin assumed leadership of the Alabama Law Enforcement Bureau, whose undercover agents were engaged in suppressing organized labor activities within the state. In 1921, he corresponded with Governor Thomas Kilby, advocating for the state’s authorization to sell “non-intoxicating near beers” under a state license, as permitted by the Volstead Act.

Austin was a Master Mason, and a member of the Knights of Pythias and the Order of Odd Fellows. He died on December 2, 1934, and is buried at Forest Hill Cemetery.

Proposals, Renovations, and Future Plans

By the 1980s, the Brown Marx Building operated under the name “Brown Marx Tower.” In 2002, Inman Park Properties purchased the Brown Marx Tower along with the neighboring Empire Building. The following year, they proposed to convert the Brown Marx into over 100 loft apartments. In preparation for the planned renovation, they moved most of the building’s tenants to the Protective Life Company building, then known as Commerce Center. After failing to negotiate a deal with the Birmingham Parking Authority to build a new deck adjacent to the site, they abandoned the renovation of the Brown Marx.

A group of local investors led by former Pride Restaurants owner Arnold Whitmore announced plans in 2006 for a $22 million renovation of the building, including 108 condominiums, a roof-top pool, gym, spa, a top-floor bar, an executive office suite, and ground floor restaurant, office, and retail space. The renovation would also include a 200-space parking garage adjacent to the building. That same year, covered walkways were installed to protect pedestrians from falling glass from upper-story windows. In 2009, a strong windstorm loosened part of the building’s metal facade. In response, the City of Birmingham entered into an emergency contract to remove the metal in the interest of public safety.

In 2012, Hughes Capital Partners purchased the Brown Marx Tower and moved its offices to the adjoining annex building. In 2017, the company removed the covered walkways to clean up around the building.

In January 2018, the Brown Marx Tower was sold to Ascent Hospitality, developer of the Elyton Hotel (Empire Building), for $3.66 million. In 2019, the company cleaned up the property and carried out some stabilization. Over the years, work would continue on the building, but no plans have been announced.