| City/Town: • Chalkville |

| Location Class: • Community |

| Built: • 1938 | Abandoned: • 2012 |

| Status: • Abandoned |

| Photojournalist: • David Bulit |

Table of Contents

State Training School for Girls

The Alabama State Training School for Girls in Chalkville was founded in 1899 in the West End neighborhood of Birmingham and was originally known as the “Home for the Friendless.” In 1909, funds were appropriated through the state Legislature allowing for the purchase of a large two-frame house with double porches in East Lake. The matron of the facility, Ophelia L. Amigh, had 25 years of experience dealing with delinquent girls at the State Institution of Illinois before taking her post at East Lake.

The girls were taught dairying, vine and berry culture, flower growing, chicken raising, and “domestic science;” cooking, cleaning, and sewing. The small institution was modeled after the Mercy Home Industrial School for Girls operated by the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union. The home was “organized for the purpose of providing a home for helpless and dependent women and children of Alabama, and also an industrial school for white girls in Alabama.” Amigh’s plans for the institution were to eventually have and operate a large farm similar to that of Bedform Reformatory in New York, now a correctional facility for women.

The State Training School for Girls expanded to include four cottages to accommodate up to 25 girls each, a chapel, and outhouses for laundry, cooking, etc. The main house was used for school and dining purposes. The rules strictly regulated the women’s lives, including their dress, church involvement, bedtimes, and contact with the outside world.

Many of the girls admitted to the school were regarded as “feeble-minded,” daughters of farmers who drifted into the city for work or “immoral purposes.” Many were illiterate and were simply seen as profits by their parents, “never remembering a mother’s caress.” All the girls were between the ages of 9 and 18 and were kept at the school for at least two years.

Alongside the State Industrial School for Girls were the East Lake Orphans Home and the Alabama Boys Industrial School which was founded in 1900 by Mrs. R. D. Johnston. Unlike the girls, boys were more independent and were taught a number of business courses. Some of the trades taught to the boys included agriculture, dairying, shoemaking, printing, cooking, tailoring, woodwork, pipe fitting, machinery, carpentering, and laundry work.

The state government was criticized for spending more money on the Boys Industrial School, and not giving the same consideration to the girls institution. In 1922, the State Training School for Girls at East Lake burned to the ground. After much demand, the institution was moved to Chalkville, 15 miles outside of Birmingham, and built on the former country estate of General Louis V. Clark.

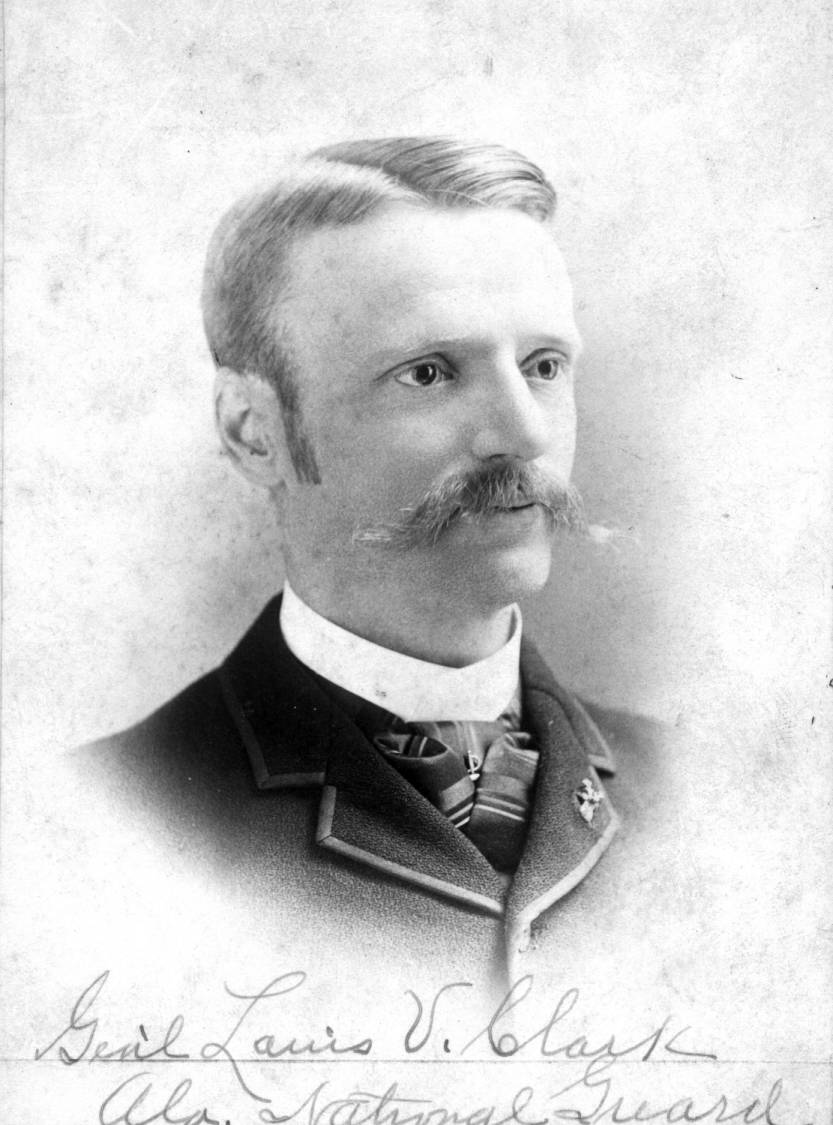

Louis V. Clark, Brigadier General

Louis Verdier Clark was born on April 1, 1862, in Marietta, Georgia, the youngest of eight children born to Francis Barnard Sr. and Helen Mary Shepherd Clark. His family moved to Mobile, Alabama, when he was an infant. His oldest brothers Gaylord Blair and James Shepard served in the Confederate army during the Civil War along with his father. After he returned from war, Francis Barnard Sr. served as chairman of the Mobile & Ohio Railroad and later president of the Mobile & Alabama Grand Trunk Railroad, both of which were acquired by the Southern Railway Company.

Louis Clark was educated in private schools in Mobile and earned his bachelor’s degree at the University of Alabama in 1885. Setting aside his plans to study medicine, Clark became the editor, manager, and part-owner of the Mountain Eagle newspaper in Jasper. He soon moved to Birmingham and invested in real estate.

He developed the Clark Building in 1908 and the Lyric Theater and office building in 1914, as well as the Capital Park Inn on the corner of Goldthwaite and Herron Streets in Montgomery, across from the old Capitol Motor Company dealership. Clark was also one of the founders of the Birmingham Little Theater in 1927 and helped develop their theater building across the street from his house at Caldwell Park. His daughter donated the building to the University of Alabama in 1954 and it was known as the “Clark Memorial Theater” in his honor until 1999.

Military Career

While at the University of Alabama, Clark served as Captain of Company E, Tuscaloosa Cadets, and led his fellow cadets to first honors in a drill competition at the New Orleans Cotton Centennial Exposition in his senior year.

After his move to Birmingham, he reorganized the Jefferson Volunteers on April 27, 1887, and outfitted the company in a style that earned them the nickname “The Alabama Zouaves” after the renowned Zouaves of the French Army before they were formally enrolled into the state militia as the 2nd Regiment, Alabama State Troops.

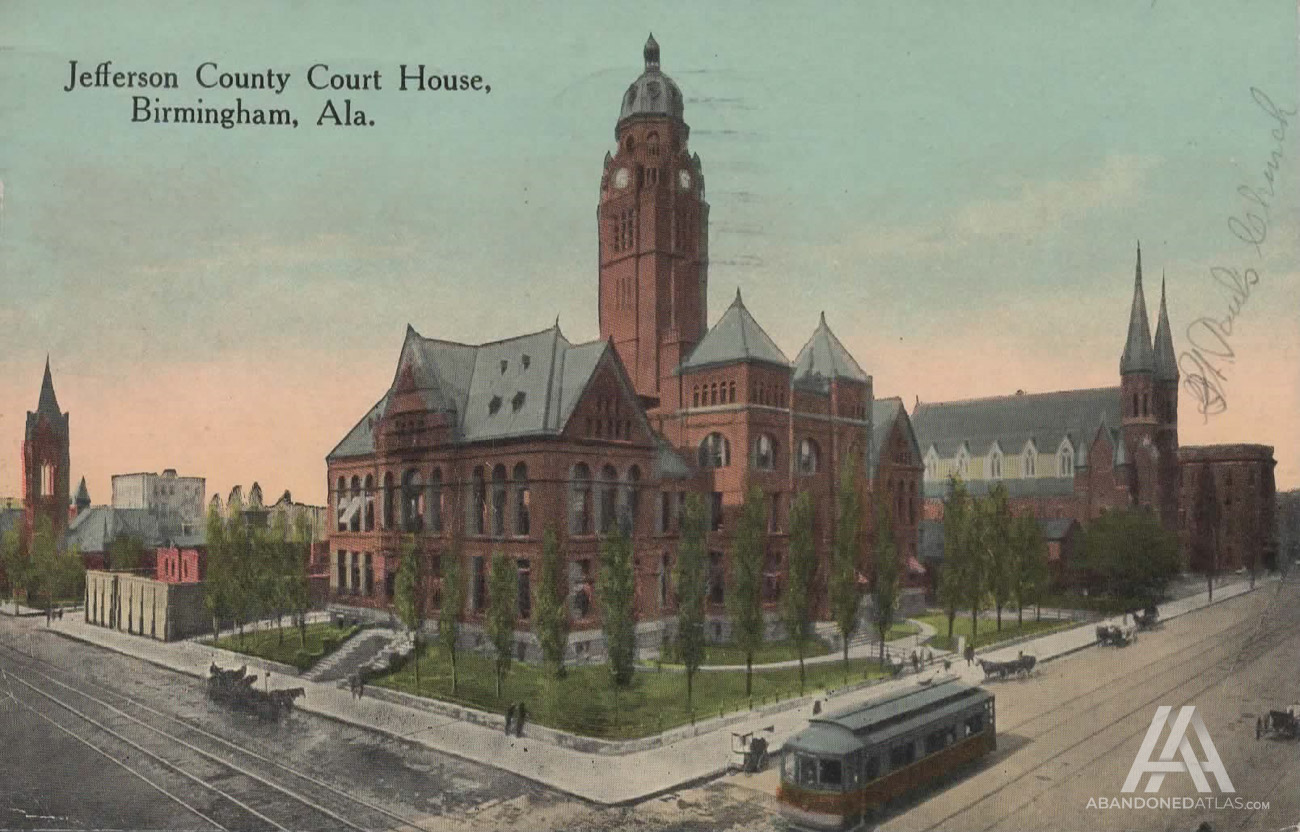

Clark’s regiment consisted of twelve infantry companies, two cavalry troops, and an artillery battery. The unit was charged with preserving public order and was often employed to suppress labor unrest in the Birmingham District, such as during the bituminous coal miners’ strike of 1894, a nationwide strike demanding higher wages. The regiment was also activated during the riot that followed the arrest of Richard Hawes for the murders of his wife and daughters in 1888. A lynching mob of 2,000 people converged on the Jefferson County Jail resulting in the deaths of ten people after authorities fired on the crowd, although no members of Clark’s companies were involved in those killings. He was proud that his forces had neither taken nor sacrificed a life under his command.

He also headed a column of 800 cavalries in a Birmingham parade to celebrate the election of Grover Cleveland in 1892 and marched behind President Teddy Roosevelt in the dedicatory parade opening the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St Louis, Missouri, where Vulcan represented Birmingham.

During the Spanish American War, the Jefferson Volunteers were under the command of Hughes Kennedy. Another company, made up of volunteers from Pratt City and Talladega, was enrolled as Company M of the 1st Regiment, Alabama Volunteer Infantry, officially dubbed the “Bowie Volunteers,” but almost unanimously referred to as the Clark Rifles for Clark’s hand in assembling the group.

Clark succeeded Thomas Jones as Colonel of the 2nd Alabama State Troops Regiment when Jones was sworn in as Governor of Alabama and was promoted to Brigadier General in 1897 by Governor Joseph Johnston. Clark retired as head of the Alabama National Guard in 1915 and died on March 13, 1934.

Matzuyama

In 1912, constructed completed on Clark’s summer country estate near Chalkville, Alabama, which he named “Matzuyama” after the Japanese castle of the same name, one of twelve Japanese castles to still have its original tenshu. The buildings took inspiration from the Wayo Kenchiku Japanese-style architecture and featured authentic Japanese furniture. The grounds were decorated with trees, shrubs, and flowers from Japan.

Matzuyama was regarded as “one of the most charming country estates around Birmingham.” A tea party hosted by General Clark’s daughter, Augusta Carlisle Clark Noland, was described in The Birmingham News as “an interesting tea service arranged on a characteristic Japanese table and tea wagon adorned with bowls of yellow garden flowers that looked as if they might have been imported from far-away Japan.” The country estate was sold to the State of Alabama for $25,000 in 1918.

Some of the old buildings on the land were refurbished and reused as the superintendant’s office, and the matron’s home for school purposes. These buildings kept the easily identifiable Japanese-Style architecture while integrating a log cabin design using locally harvested wood. The school building was briefly known as Matzuyama after its opening. A lake was dug and several hundred fruit and nut trees, and grapevines were planted. Plans were made to make the school as self-sustaining as possible.

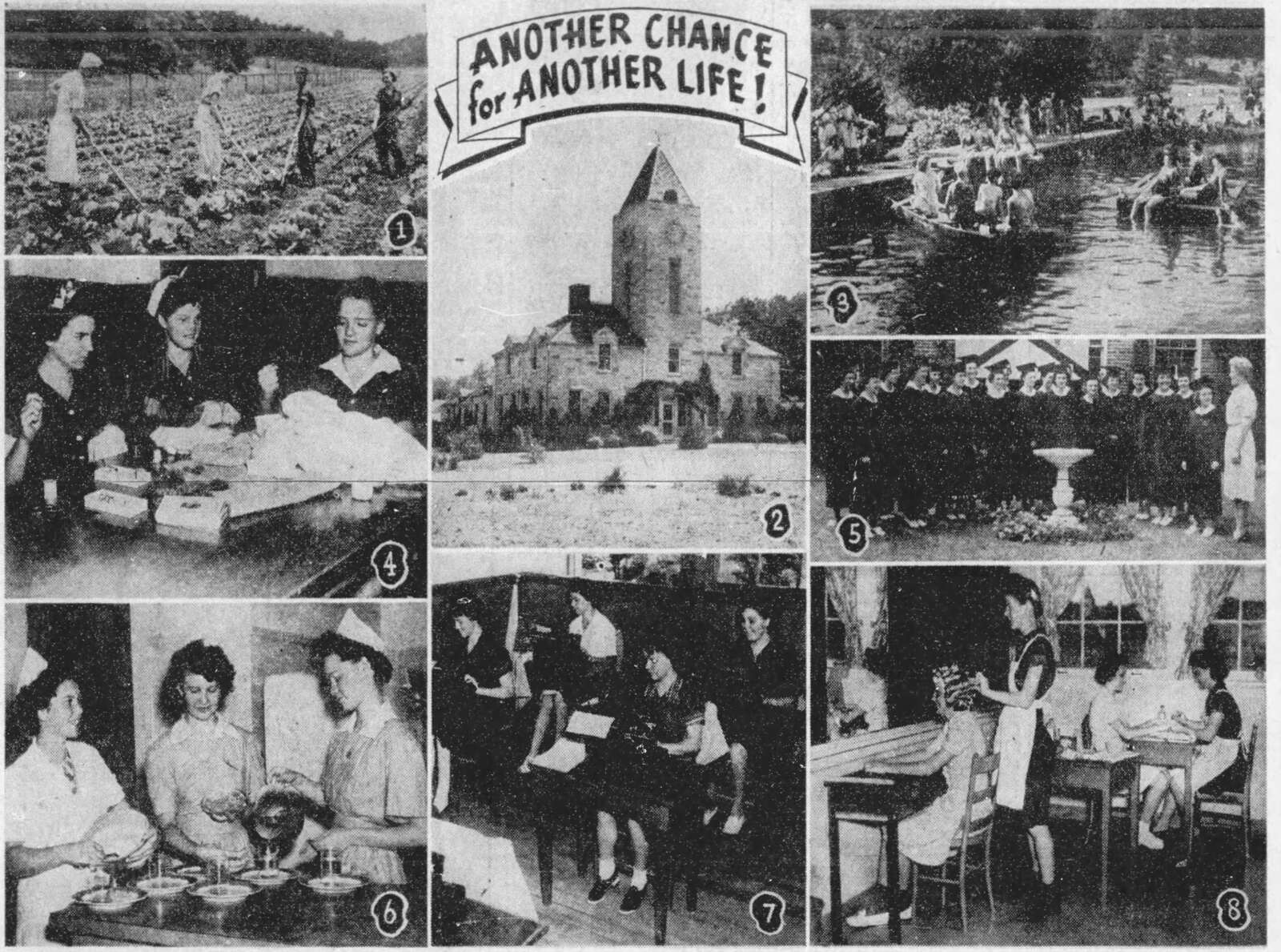

WPA Project Expansion

Since its inception, the State of Alabama took advantage of Present Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, with the Civil Works Administration providing $17,500 for material and $60,000 for labor on the construction of the school. The State Training School for Girls was expanded in 1938 which included the addition of new cottages, a swimming pool, a church, and an administration building that contained a hospital and clinic. The work was undertaken by the Works Progress Administration with the stone used being cut from a nearby quarry and supplied by the Civilian Conservation Corps.

The State Training School for Girls was regarded as the most modern school of its type in the country and offered facilities for 125 girls and school personnel. The final estimated cost of the project was $197,372, most of which was provided by the federal government.

Trouble at the school

Dating back to the 1940s, the school has been plagued with problems committed by both staff and the girls of the reformatory. In 1949, the Birmingham Federation of Labor investigated allegations that the conditions at the school were deplorable. The inmates received very little training, awful food, and recreational facilities were poor. Mary S. Fowler, superintendent of the institution, admitted that disorderly inmates were locked in their rooms and their hair was cut short as punishment, but that it was the extent of the ill practices there.

Escape attempts were often with girls explaining that they want to “get out.” In December 1951, eight girls broke out of the school’s detention hall by smashing the bars off a window. Two of the girls were apprehended before they were able to make it off the premises, one of which had a slight cut on her hand from the broken glass in the window. The chairman of the school’s executive committee responded to the incident, saying that most of the unrest and “trouble” at the school was caused by “borderline mental cases” which should be at Bryce Hospital, the state’s insane asylum.

Officials explained that girls were much more problematic than boys as boys tend to “act out” while girls “tend to go into themselves.” They said, “Most of the girls have felt that Dad has not loved her, has loved but not admired her mother, and has been cold to her or abused her. The girl gets the idea it’s no good to be a girl and she begins to act out in masculine ways by drinking and smoking in excess and bragging about sexual exploits. The girls have not known fair and consistent discipline. They have failed in school and in wholesome social relationships. Their goal becomes “get married as soon as you can, have as many children as I can, and try to put up with life,” and this girl wonders why life doesn’t offer her more.”

Sexual Abuse and Neglect

In 2001, more than a dozen girls went public with the allegations, which also included claims of physical abuse and consensual sex between teen girls and adult staff at the State Training School for Girls, and filed multiple federal lawsuits against the State’s Department of Youth Services. They alleged that between January 1993 and June 2001, they were “sexually assaulted, strip‑searched by male guards, beaten, capriciously tossed into solitary confinement, denied medical attention, pressured to have abortions, and threatened with retaliation if they complained.”

Some of the girls were interviewed by Amy Singer for Marie Claire magazine, with those interviews being published in June 2002. Here are a few select quotes: “Take the case of Sandy Jones. Until recently, the nervous 19‑year‑old couldn’t bear to tell even her own mother about what had happened to her. After entering Chalkville five years ago for being expelled from school and running away from home, she says a guard came into her room one night with a proposition. “He said if I had sex with him, I could get out [of the facility] early.”

The offer wasn’t a complete shock: Sandy had already heard that Chalkville guards offered such bargains, and that many students traded sexual favors for small pleasures, such as snacks and cigarettes. Desperate to visit her terminally ill grandmother, Sandy agreed to sleep with the guard. “I had sex with him,” she says, “but I didn’t want to.“

She immediately regretted it. When the guard began to return to her room regularly, she refused his advances. But her roommate did not. At night, Sandy tried to sleep while they had sex in the bed next to hers; during the day, the guard punished her for rejecting him, piling on work and extra exercises.

Sandy endured this treatment—along with propositions from other male staffers—throughout her 10‑month stay. She says she and others repeatedly reported the situation to the superintendent, “but he didn’t believe us. There was nothing more we could do.”

Amanda Twitty, another former inmate, said that she “entered the facility at 17 for multiple probation violations. But she says that before she got there she had been diagnosed with cervical cancer, and that the staff refused to let her keep a previously scheduled doctor’s appointment. She says her subsequent requests for medical attention were ignored—as were her complaints about abdominal pain during daily physical training. “The exercises made my stomach hurt even more,” she says. “I’d be doubled over in pain. It felt like I had my period 24 hours a day, seven days a week.“

Amanda says alerting the staff to her pain often resulted in punishment. “The guards would call me a crybaby and tell me to get up,” she says. “If I said anything, they’d make me do even more push‑ups.“

These are just a couple of the stories involving the abuse at the State Training School for Girls. After the allegations were made public, the state suspended 11 of its 15 staff members and hired a new administrator. Throughout the years, more lawsuits were filed in different courts throughout the state, increasing the number of plaintiffs. The lawsuits were combined for settlement purposes. It wasn’t until February 2002, that the federal lawsuit was settled with $12.5 million paid out to the plaintiffs.

Closure and Abandonment

By the morning of January 23, 2012, the population of the State Training School for Girls had been reduced to 18 girls due to Alabama’s juvenile justice reform efforts. On that morning, an EF3 tornado with winds of 150 miles per hour swept across north Jefferson County. Eight buildings on the campus were damaged beyond repair, including the cafeteria, the school, and the gym, which were essentially leveled by the tornado. Miraculously, the dormitory housing the girls and the eight staff members on duty that day was the least-damaged building on the entire campus with not a single person being injured.

Before the tornado, the state’s Department of Youth Services was dealing with the fiscal dilemma of operating a facility meant for 150 inmates with a population of 18. Because of its size, the facility also employed 70 workers. A decision was made not to rebuild the old Chalkville campus and instead, to design a construct an all-new state-of-the-art facility. The damaged buildings at the campus were demolished and the site was cleaned up for future use.

The reaming four buildings were repaired with the possibility that the property would be used by another state agency or other governmental entity. The campus would never be reused and the State Training School for Girls has been abandoned for nearly a decade now. It has exceedingly fallen into ruin over the course of these years. While the idea of demolishing the remaining buildings has been talked about, there are currently no plans for the site.

Photo Gallery

References

The Birmingham News. (December 21, 1913 p. 46). THE REAL CHRISTMAS IS BEING PLANNED FOR BIRMINGHAM

The Birmingham News. (August 20, 1914 p. 8). Miss Augusta Clark Honors Her Guest at Tea

Birmingham Post-Herald. (August 8, 1915 p. 3). What the State Training School for Girls Is Doing for the Womanhood of Alabama

The Birmingham News. (January 19, 1949 p. 6). Girls’ Training School Head Opens Doors In Face Of Inquiry Demands

The Birmingham News. (December 11, 1951 p. 1). Eight training school girls flee; two taken

Mary Ellen Mark; Amy Singer. (June 2002). Girls Sentenced to Abuse