| City/Town: • Mobile |

| Location Class: • Residential |

| Built: • 1914 | Abandoned: • ca. 1980 |

| Status: • Burned Down • Demolished |

| Photojournalist: • Russ Gorbaty |

Table of Contents

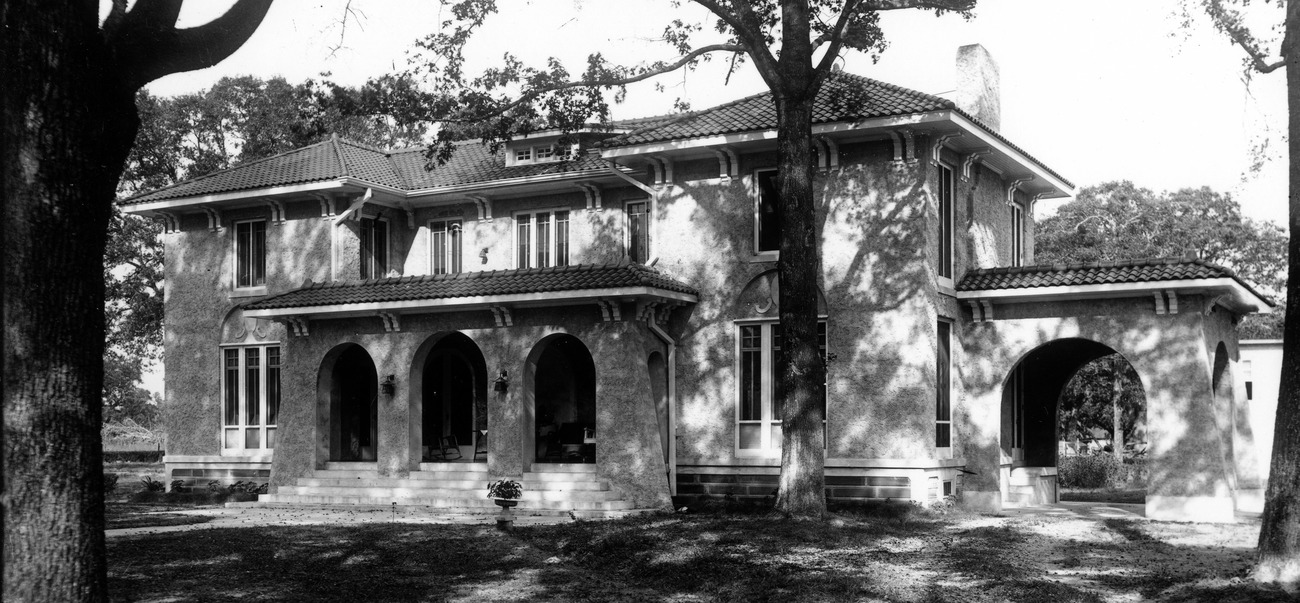

George Cabell Outlaw Sr.

George Cabell Outlaw, son of Tiberius Gracchus and Belle Garner Outlaw, was born in Mobile, Alabama, on July 19, 1886. After completing his secondary education at the University Military School in Mobile, he attended the University of Virginia and transferred to The University of Alabama Law School where he received his degree in 1917. Outlaw began work with the Bureau of Investigation, the predecessor of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, shortly thereafter. Although Outlaw investigated anti-war sentiments and draft dodgers during World War I, some of which were among shipyard workers in Mobile, he was also involved in investigating the burgeoning Ku Klux Klan.

In February 1915, the D. W. Griffith film, Birth of a Nation, debuted in Los Angeles. The film glorified the short-lived, post-Civil War white supremacist group called the Ku Klux Klan. The film also revived interest in the KKK, leading to the birth of several new local groups later that same year. During the early formative years of the Bureau, there were few federal laws to combat the KKK, but under its general domestic security responsibilities, the Bureau was able to start gathering information and intelligence on the Klan and its activities.

Archive records from the Bureau identify an agent by the name of G. C. Outlaw based in Mobile in June 1918. According to records, Outlaw investigated a threat made by the Ku Klux Klan against the leader of a multicultural group. Outlaw learned that Ed Rhone, the leader of a multi-racial group called the Knights of Labor, was worried by the abduction of another labor leader by reputed Klansmen. Outlaw noted that “this uneasiness of the Knights of Labor is the first direct result of the Ku Klux activities.” The Ku Klux Klan was investigated and Outlaw assured Rhone that the Bureau would protect him from any possible harm.

Morrison’s Cafeteria

After World War I came to a close, Outlaw left the Bureau and opened a law practice in Mobile in 1919. It was around this time that he met a businessman and restauranteur by the name of James Arthur Morrison. Morrison talked Outlaw into investing in the fairly new concept of the cafeteria-style restaurant. Partnering with Morrison, the first Morrison’s Cafeteria opened on September 4, 1920, on the corner of St. Emanuel and Conti Streets in downtown Mobile.

Morrison’s Cafeteria was an instant success and went beyond either Morrison’s or Outlaw’s immediate expectations. Other markets were examined for a Morrison’s Cafeteria and in May 1921, a second cafeteria was opened in Pensacola, Florida. Due to the success, Morrison Cafeterias Consolidated, Inc. was formed with Morrison as President and Outlaw as Secretary-Treasurer. By 1927, the new corporation had opened thriving cafeterias in three more cities—Jacksonville, Florida; Savannah, Georgia; and New Orleans, Louisiana, where the largest cafeteria in the South opened in the former Fabacher Rathskeller on St. Charles Street. At its peak, the company expanded to more than 150 restaurants that offered meals 365 days a year with more than 100 food items prepared “homemade” daily.

To further expand the corporation’s operations, Outlaw decided to sell public stock which brought outside capital into the enterprise. Four more cafeterias were opened in Florida—in Tampa, St. Petersburg, Orlando, and West Palm Beach. Due to the high-quality food and reasonable cost, Morrison’s Cafeteria operated unhindered during the Great Depression, offering breakfast for a nickel, lunch for an average of thirty-five cents, and free ice cream and cake on Thursday “Family Nights.”

When World War II and rationing ended, the company expanded to include several more subsidiaries, including Morrison’s Merchandising Corporation, Food Service Equipment Company, Morrison’s Assurance Company, Morrison’s Chemical Company, and Gill Printing Company. This structure permitted Morrison’s to manufacture and distribute nearly every operational need from detergent and cleanser to coffee and the stainless steel equipment used in the kitchen and interior decoration and allowed the company to become one of the most efficient in the food-service and restaurant industry. It was also around this time that James Morrison sold his interest in the company and retired to Florida.

George Cabell Outlaw, Sr., died on July 16, 1964. After his death, Morrison’s continued to grow having acquired the Ruby Tuesday chain of restaurants in 1982. By the mid-1990s, the new restaurant concepts, particularly Ruby Tuesday, were doing far better than the original cafeteria chain, as customers’ expectations and tastes had changed. Because of this, Morrison’s decided to split the company: Morrison’s Fresh Cooking, the cafeteria chain; and Ruby Tuesday, Inc., which also included the other casual dining concepts.

By 1998, Morrison’s Fresh Cooking was unable to withstand the loss in popularity of cafeterias in general and sold out to Piccadilly Cafeterias. Unable to compete with today’s fast food and casual dining restaurants such as Applebee’s and Chili’s, they’ve reduced their number of locations to around 30, while maintaining one location branded as a Morrison’s Cafeteria in the former chain’s hometown of Mobile.

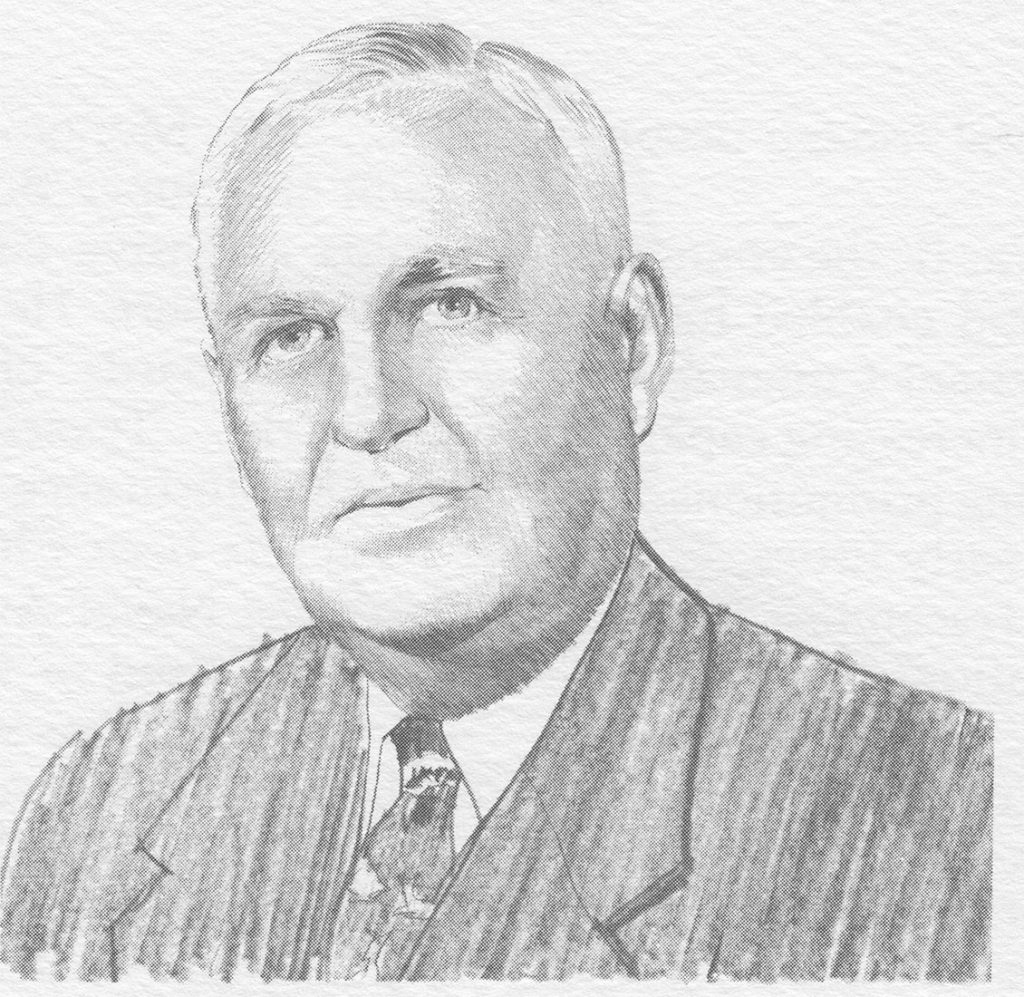

Outlaw House

Known as the Outlaw House, this house was constructed in 1914 and designed by local architect George Bigelow Rogers in the Spanish Colonial Revival style of architecture. Rogers is recognized for bringing this style to Mobile in 1904 with the George Fearn House. He also designed the highly elaborate Government Street United Methodist Church which is considered one of his finest works. Rogers designed many of Mobile’s notable historic structures, most of which are listed on the National Register of Historic Places including the Murphy High School Complex, the Bellingrath Gardens and Home, The Dave Patton House, and the Van Antwerp Building.

Although it’s unknown who the home was constructed for, the property was acquired by G. C. Outlaw sometime in 1925. According to local legend, he acquired the property in a poker game. At the time, the house included 120 acres of land where he built a lake known as Outlaw’s Lake by constructing a dam to stop the flow of a natural spring. The dam was used to generate electricity, the first in the area to have electricity and a telephone, which he later expanded by supplying other houses in the area. Down in the basement, an oil furnace provided heat and it was even said that there was an underground tunnel that went from the basement to the lake across the street.

In the 1940s, G. C. Outlaw moved to the city along with his wife Mayme Ricks, and their two sons, George Cabell Jr., and Arthur Robert Outlaw.

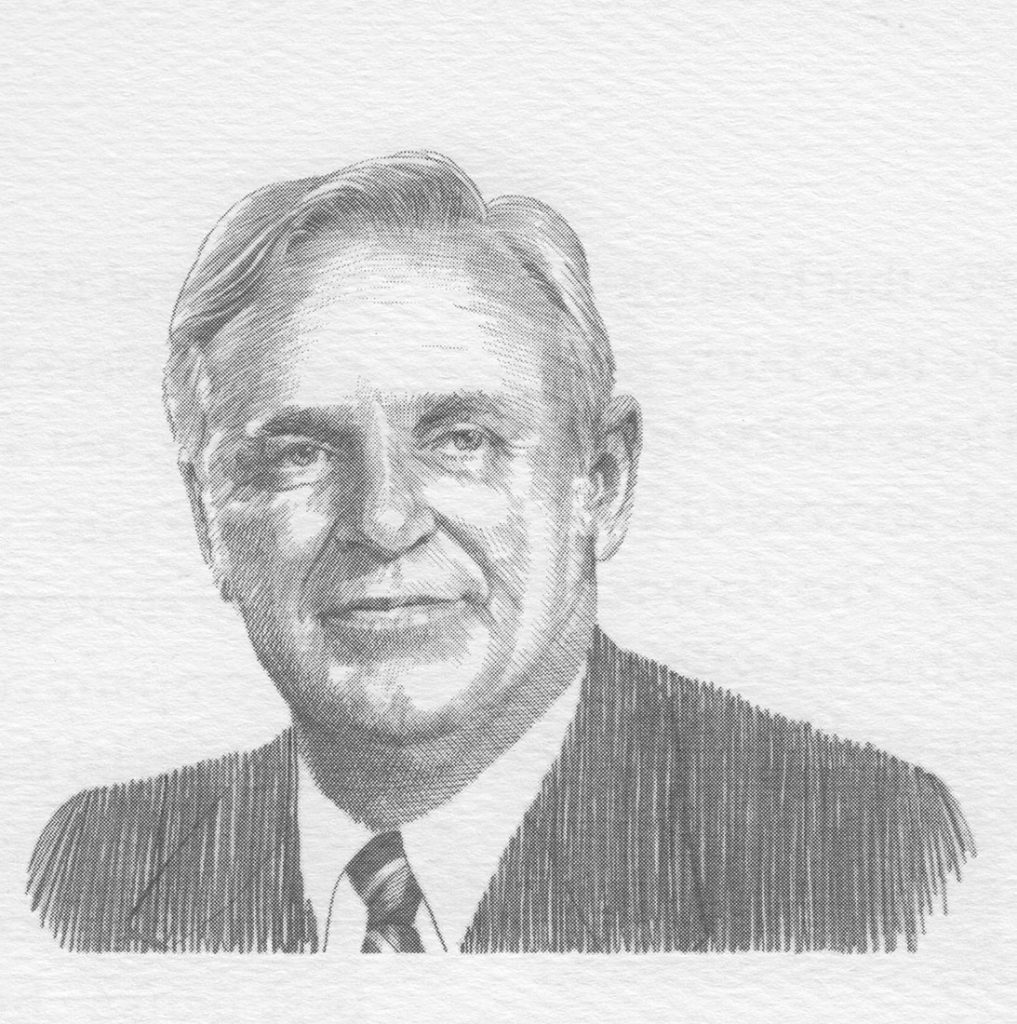

Arthur Robert Outlaw

Arthur Robert Outlaw was born on September 8, 1926. He attended Catholic schools in Mobile and graduated from the McGill–Toolen Catholic High School in 1945. He enlisted in the U. S. Air Force Cadet Program, serving for two years during the last months of World War II and afterward. After returning to Mobile, he attended the University of Alabama for one year and received his business degree at Spring Hill College.

In 1951, Arthur started working as an auditor in his father’s business, Morrison’s Restaurants. He and his father continued to develop the business together during the next two decades when it became the largest cafeteria chain in the nation. He advanced to serve as the vice-chairman of the board and director of Morrison Restaurants, Inc. after his father’s death in 1964.

Arthur entered politics in 1965, serving as the Public Safety Commissioner of the city of Mobile until 1969 when he returned his attention to his various business endeavors. The government at the time had three non-partisan commissioners elected at large, each with specific responsibilities. In addition, they rotated the position of President of the Commission/Mayor for one-year terms during their service on the commission. Because of this, Arthur also served as Mayor of Mobile between 1967 and 1968.

After several years in business, he returned to politics, being elected as Finance Commissioner of the city in 1984. Running as a Republican, Arthur was elected Mayor in 1985. As mayor, he was committed to investment in downtown Mobile to stimulate redevelopment and attract new businesses. His administration proposed the construction of a convention center in 1987. It was part of a 15-year plan for redevelopment.

He lost re-election in 1989 to Mike Dow who promoted himself as a new-style candidate, reaching out to both black and white voters. Dow’s campaign included a coalition of African-American ministers and he frequently attended mass at African-American churches throughout the city. He also campaigned against the construction of the convention center. Dow’s victory was based on his support among middle-class white voters and African Americans while Arthur Outlaw carried the upper-class white vote. Despite campaigning against it, he helped carry out Outlaw’s 15-year plan for downtown Mobile, including the construction of the convention center which was named the Arthur R. Outlaw Mobile Convention Center in his honor.

In the 1960s, Arthur renovated the old Outlaw home and leased the property to the local police chief. He later moved into the house with his family in the 1980s. In order to run for Mayor of Mobile though, and to avoid any conflicts, he and his family moved within the city limits, leaving the Outlaw House vacant ever since. On the morning of July 9, 2021, the Outlaw House was destroyed in a fire and what remained of the home was demolished on December 1, 2021.

Photo Gallery

Video Gallery

References

Alabama Business Hall of Fame. (retrieved December 8, 2022). George Cabell Outlaw, Sr.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation Archives. (February 26, 2010). The FBI Versus the Klan

Alabama Business Hall of Fame. (retrieved December 11, 2022). Arthur R. Outlaw

The Montgomery Advertiser. (January 18, 1943 p. 26). Morrison’s Pioneered Cafeteria Idea in South—Reward Is Great