| City/Town: • Hope Hull |

| Location Class: • Educational |

| Built: • 1922 | Abandoned: • c. 1967 |

| Historic Designation: • National Register of Historic Places (2008) • African American Heritage Site • Historic District (2009) |

| Status: • Abandoned |

| Photojournalist: • David Bulit |

Table of Contents

The Rosenwald Fund

The Tankersley Rosenwald School is a one-story, rural school built for underprivileged African American children. It was built with funding from the Rosenwald Fund, established in 1911 by Julius Rosenwald. Rosenwald became part-owner of Sears, Roebuck and Company in 1895, serving as its president from 1908 to 1922, and chairman of its board of directors until his death in 1932. By the 1910s, Rosenwald was beginning to gain recognition for philanthropic efforts, particularly the donation of funds to hospitals, universities, and YMCAs, including segregated black YMCAs in several cities.

After reading a biography of William Henry Baldwin Jr., the chairman of the Tuskegee Board of Trustees who died on January 3, 1905. In 1911, while serving as president of Sears, Roebuck and Company, Rosenwald met with Booker T. Washington, the country’s foremost black educator and found of the Tuskegee Institute in Tuskegee, Alabama. The philanthropist was impressed by the contrast between the “decadent rural surroundings and the energy and achievement he saw at the institute.” The following year, Rosenwald accepted an invitation to become a trustee of the institution, funneling large sums of money into what would become known as the Rosenwald School Building Fund Program.

Rosenwald School Program

The rural school building program was instrumental in bridging the gap between the segregated public schools where black schools were extremely underfunded. These schools, constructed to models designed by architects of Tuskegee Institute became known as “Rosenwald Schools.” This program for African-American children was one of the largest programs administered by the Rosenwald Fund. Over $4.4 million in matching funds stimulated the construction of more than 5,000 schools, as well as shops and teachers’ homes, mostly in the Deep South. Rosenwald also funded the construction of larger schools such as the Chilton County Training School.

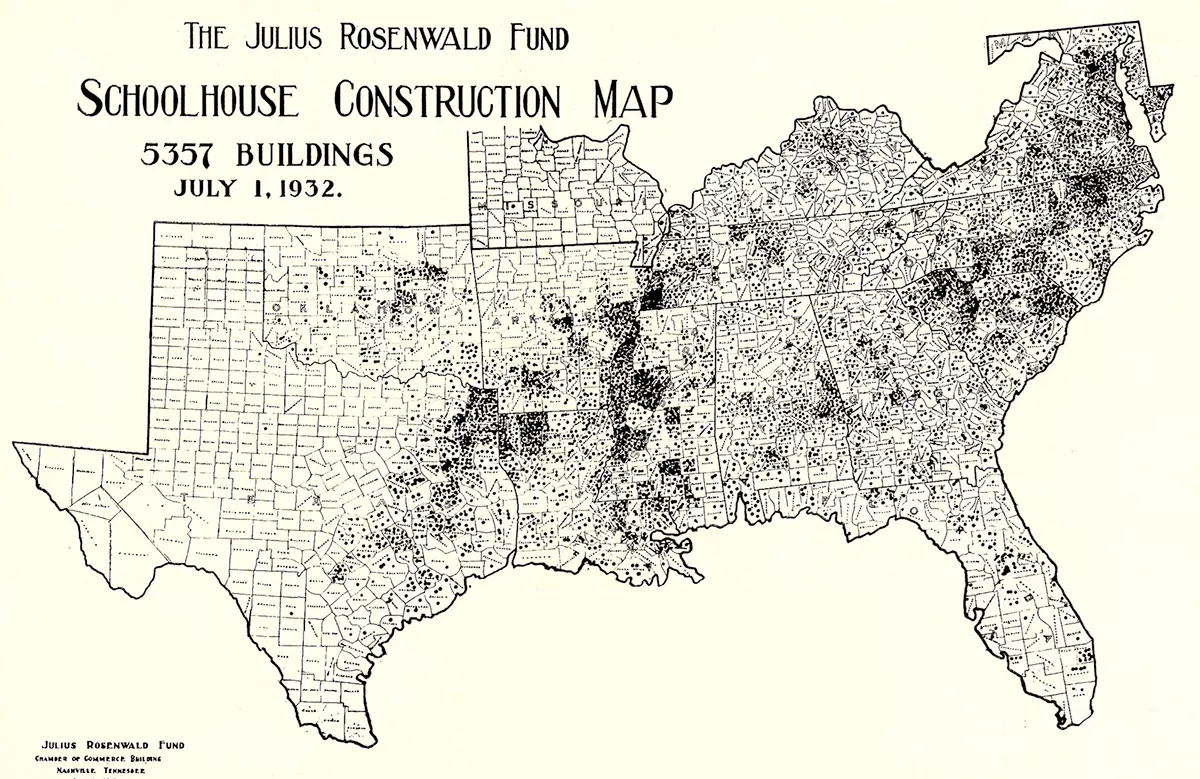

In the journal article, “The Rosenwald Schools and Black Education in North Carolina,” published in October 1988, author Thomas W. Hanchett wrote, “In the short run, the Rosenwald Fund had an impressive effect. By the 1930s thousands of old shanty schoolhouses had been replaced with new, larger structures constructed from modern standardized plans.” By the time the fund shut down its school building program in 1932, “over 5,300 Rosenwald buildings blanketed fifteen southern states.“

“The Rosenwald program constituted an important but limited avenue for the advancement of black education during much of the first half of the twentieth century…By July 1, 1932, a total of 5,357 Rosenwald schools, shops and teachers’ homes stood in 833 counties of fifteen southern states, erected at a cost of $28.4 million. The Rosenwald Fund’s donation of some $4.3 million had sparked $4.7 million in black contributions. Local governments had in turn contributed $18.1 million or 64 percent of the total with private local white contributions making up the remaining 4 percent.

“The Rosenwald classrooms provided generations of black children with real educational opportunities and a number of schools operated until after World War II.” Unfortunately, while the Rosenwald School Building Fund did improve rural school facilities, it fell short of obtaining the far-reaching impact Washington and Rosenwald envisioned. The attitudes of southern whites were little changed by Rosenwald grants and few whites were induced to contribute to the building fund. “School boards continued to let public investment in black education lag even further behind than in white schools…the problem of school inequality would not begin to crack until a generation later, under pressure from a different strategy. Starting slowly in the 1950s with the United States Supreme Court decisions Sweatt v. Painter and Brown v. Board of Education and accelerating through the 1960s and into the 1970s, African-American activists and white liberals brought the power of the United States government to bear on southern school boards.”

Tankersley Elementary School

Built around 1922, the Tankersley Rosenwald School is located in a rural area 10 miles south of Montgomery in Hope Hull. It’s situated on 3.15 acres of land which originally contained 15 acres; ten were in timber and the school and playground took up five acres along with the building. The property also contained two sanitary privies, two water pumps, a basketball court, a baseball diamond, a pecan grove, and a garden which were cleared or torn down after the school closed in 1967.

According to the National Register of Historic Places in 2008, the Tankersley Rosenwald School is a “one-story, T-shaped building that is clad in weatherboard and rests on a foundation of red brick piers approximately 18″ above ground. The foundation was partially stabilized and the building’s exterior was repainted white in 2007. The roof, which includes a front gable set perpendicular to the main roof ridge, was pierced by three plain interior chimneys of red brick. Today, only one chimney remains visible from the outside. A new asphalt shingle roof replaced the earlier standing sheet metal roof in 1997. However, the wide, overhanging eaves retain their exposed rafter ends and brackets. Tankersley Rosenwald School was constructed with Bungalow/Craftsman stylistic elements typical of the Rosenwald pattern with an east-west exposure to take advantage of natural light. The building remains in fair condition with a fairly high degree of architectural integrity.

The five-bay wide front facade faces east. It is dominated by a shallow, gabled wing featuring a bank of four 9/9 double-hung sash windows and, in its gable peak, a square, louvered attic vent. Flanking this central wing are small stoops with wide steps delimited by brick walls with concrete coping. Each stoop is shaded by a shed roof with exposed rafter ends and brackets. In each stoop area are wooden doors with each door displaying six panes of glass above two horizontal panels. The end bays each consist of a paired 9/9 DHS window. All windows are boarded up to discourage vandalism.

The western or rear elevation is four bays wide. Each middle bay is comprised of a bank of five 9/9 DHS windows. Each end bay consists of a single-leaf, five-paneled, wooden door below a shed roof with exposed rafter ends and brackets. The steps to these entries are missing.

The north and south (side) elevations each have an asymmetrically placed window and a square, louvered attic vent in the gable peak.

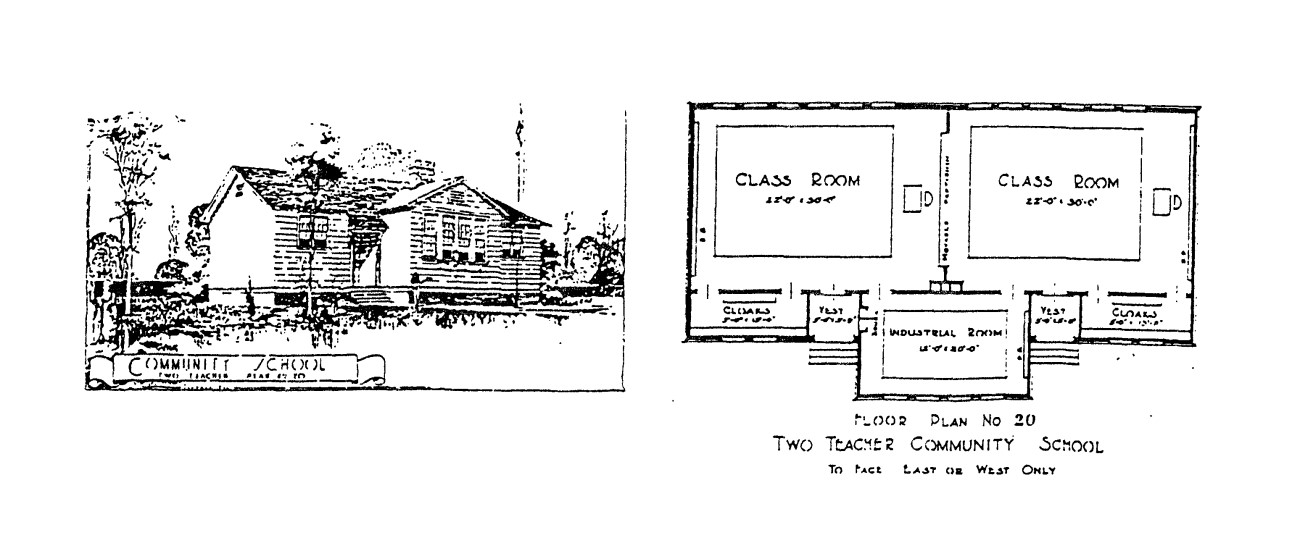

As in Floor Plan No. 20, Tankersley Rosenwald School has two classrooms divided by a partition in the main part of the building and an industrial room in the front gabled wing. Wooden, paneled folding doors comprise the partition and when these are folded back the two rooms can be used as an assembly or chapel.

The front vestibules in the Tankersley Rosenwald School access not only the main classrooms but also the industrial room whereas in Floor Plan No. 20 they only allow entry into the main classrooms. Access to the other rooms is only from these classrooms. Other modifications to the plan are on the west elevation. The original design calls for a bank of six windows in each classroom. At Tankersley, however, the western wall in each room is defined by a bank of five windows and a door to the outside. These minor changes, however, do not greatly detract from the overall integrity of Floor Plan No. 20 as illustrated by the Tankersley Rosenwald School.

On the interior, the walls and the ceilings are clad in beaded board. The height of the ceiling is about 14′ above the level of the wooden plank floor. Simple moldings surround the doors and windows. Above some of the doors are six-light transoms. The blackboards with their original moldings are still in place. The industrial arts room has its original storage closet along the east wall. An open stage remains in the south classroom and a blackboard, piano, and organ remain in the north one. Storage cabinets and storage/cloak rooms are retained in poor condition.”

The Tankersley Rosenwald School was added to the Alabama Register of Landmarks and Heritage on June 26, 2003, to the National Register of Historic Places in 2008, and again in 2009 as a part of The Rosenwald School Building Fund and Associated Buildings Multiple Property Submission.

Photo Gallery

References

National Register of Historic Places. (December 10, 2008). Tankersley Rosenwald School

National Register of Historic Places. (retrieved January 28, 2023). The Rosenwald School Building Fund and Associated Buildings MPS