| City/Town: • Tallassee |

| Location Class: • Industrial |

| Built: • 1844 | Abandoned: • 2005 |

| Status: • Abandoned |

| Photojournalist: • David Bulit |

Table of Contents

Founding of Tallassee

Prior to the founding of Tallassee, the Muskogee-Creek Indians had settled in the town of Talisi, located at the mouth of Euphaubee Creek, where it meets the Tallapoosa River, about three miles south of the current Tallassee. Located nearby was Tukabatchee which was a younger Creek settlement and the last great capital of the Muskogee Creek Confederacy. In October 1811, Tecumseh and his brother Tenskwatawa attended the annual Creek council at Tukabatchee to convince the Creek Nation to join their pan-tribal campaign against encroaching European society. Tecumseh’s ideas were met with some support, enough so that his ideas eventually led to the Creek War in 1813.

The loss of the war resulted in the loss of the Native Americans’ claim to their land as the Creek Nation was forced to cede over 21 million acres of land to the United States government. Due to the passing of the Indian Removal Act in 1830, the Creeks were forcibly removed from their land in 1832. Most of the Muskogee Confederacy were relocated to Indian Territory while others remained, having given up their tribal membership, and were considered United States and state citizens as a condition of remaining.

Tallassee Falls Manufacturing Co.

Barent DuBois founded Tallassee in 1835 when he acquired a large portion of land in the Tallassee area through deeds and grants. As early as October 24, 1835, was the town laid out and people were living in what was then known as “Tallassee Town”. In 1836, the services of the “Tallassee Guards” were offered to Governor Clement Comer Clay during the Second Creek War. In 1844, Barent Dubois and his wife Milly Reed DuBois sold the land to Thomas Meriwether Barnett and William Matthews Marks who would build Tallassee’s first textile mill and the second built in Alabama. The Tallassee Falls Manufacturing Company produced cotton first, and later wool cloth, and would remain a major part of the town’s economy for more than 160 years.

Civil War

During the Civil War, the Tallassee Guards became part of the Confederate Army. The mill supplied cloth for uniforms and tents. In 1864, with the war escalating around Richmond, Virginia, the chief of ordnance for the Confederacy Colonel Josiah Gorgas recommended moving the Richmond Carbine Factory deeper into the south. The carbine factory was moved to the Tallassee Mill where a new armory was constructed and began manufacturing Tallassee Carbines, a .58 caliber carbine patterned after the British Enfield carbine with a modified barrel, which was to become the official carbine of the Confederate cavalry. During the course of the Civil War, the town of Tallassee was never attacked by Union forces, though they came close.

Battle of Chehaw Station

In July 1864. Union Major General Lovell H. Rousseau led a raid through Alabama with a force of 2,500 cavalrymen armed with Spencer repeating rifles with the mission of burning and destroying railroads, buildings, and supplies. Upon reaching Chehaw Station, the Union forces were met with resistance by a unit of the Tuskegee Home Guard and a skirmish ensued, now known as the Battle of Chehaw Station. A train carrying a battalion of 16 and 17-year-old cadets soon joined the Confederate forces, joining the battle using old muzzle-loading muskets and a small cannon. The Union troops were ordered to withdraw after the Confederates were reinforced by a militia from Tuskegee.

As a result of the Confederate forces’ actions, the Union never reached Tallassee or the armory. Rousseau’s force would go on to complete their task of taking and burning a large number of supplies at Opelika, destroying 30 miles of track, and burning down the railroad stations and warehouse of the Montgomery and West Point Railroad.

Wilson’s Raiders

By early-1865, approximately 500 Tallassee Carbines were produced. In March 1865, Union Major General James H. Wilson advanced into Alabama with 13,000 troops with the task of destroying the arsenal in Selma. Concerned for the safety of the carbines in Tallassee, orders came down to move the rifles and all the manufacturing equipment to Macon, Georgia where the Confederacy was constructing what was to be the world’s largest small arms factory. After capturing Selma and destroying the city’s arsenal and shipbuilding facility, Wilson swung his troops towards Montgomery, capturing the city on April 12 with no resistance as its citizens and militia were ordered to evacuate beforehand.

With Robert E. Lee’s surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia on April 9, the Army of the South under the command of General Joseph E. Johnston had not yet surrendered. Wilson’s plan was to head east into Georgia to destroy the remaining arsenals and munitions, and to cause any remaining local forces to “disintegrate.” While detachments were sent to West Point, Georgia, and Columbus, Georgia, others were ordered to destroy some mills and bridges on the Tallapoosa River.

On April 15, a Union commander leading a small detachment was headed toward Tallassee, but due to an outdated map, he came to believe the small town was located on the east side of the river. Union troops found themselves at the small railroad community of Franklin, Alabama, where they were met by a superior force of Confederate militia, enough so that the Union troops were ordered to retreat. Wilson’s troops would go on to capture Macon including the Macon Armory. It is believed that the 500 Tallassee Carbines sent to Macon were destroyed upon arrival, though only 12 are known to survive today. Tallassee Mill stands as the only Confederate Armory not destroyed during the war.

The Mount Vernon Mills Co.

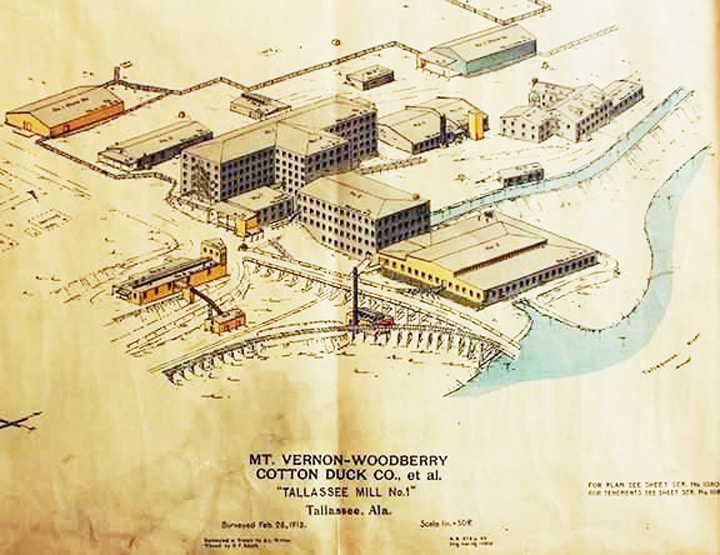

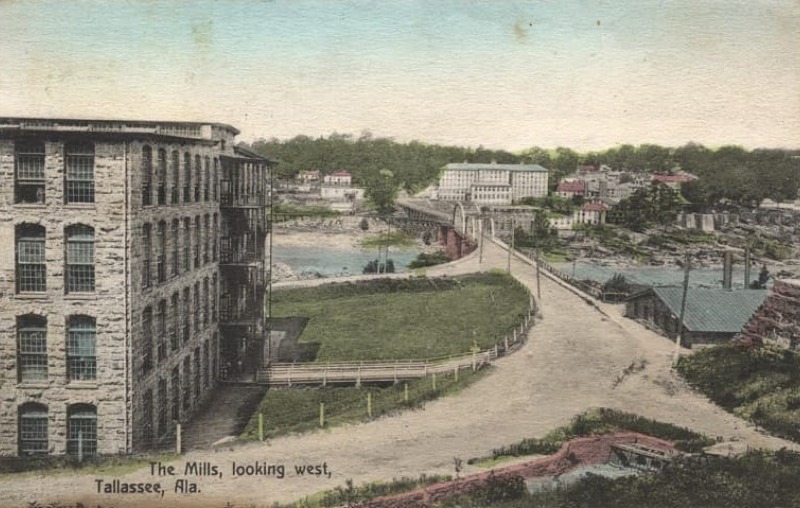

Following the war, the mill would not resume normal operation until the 1860s when it was gradually expanded. In 1878, the fifth floor was added to the mill, and a four-story cotton duck mill was constructed. In 1886, a weaving shed and picker house were also added. In 1900, the Tallassee Falls Manufacturing Company became part of the Mount Vernon-Woodberry Cotton Duck Company.

The Mount Vernon Mills Company was founded in 1849 with its first textile mill located in the Jones Falls area in what is now Baltimore, Maryland. In 1899, the company merged with the other mills in the area to form the Mount Vernon-Woodberry Cotton Duck Company, a frontrunner in the fabrication of cloth sails for clipper ships and cloth for canvas tents. It wasn’t until the company rapidly expanded in the South, acquiring mills in South Carolina and the Tallassee Mill. Two additional mills were constructed officially named Mill No. 2 and Mill No. 3 but are better known as the East Mills.

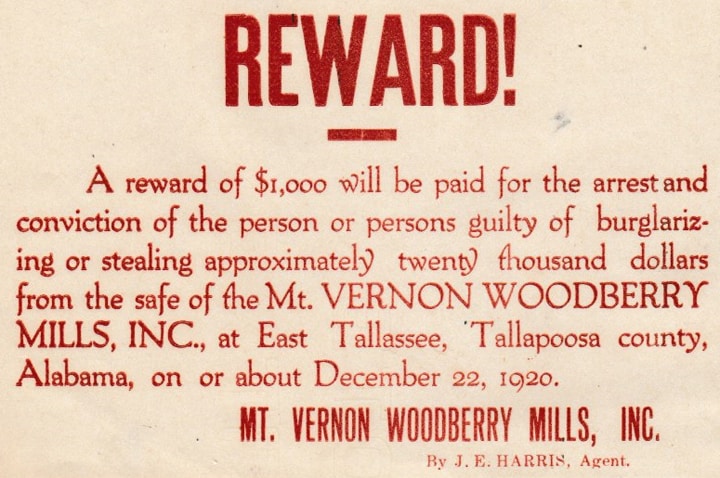

$20,000 Burglary

One notable event occurred on December 23, 1920. It was reported that thieves broke into the main office of the mill, worked the combination on the vault, and made off with $19,942. Adjusted for inflation, that’s about $293,000 in today’s economy. The company offered a reward of $1,000 for information leading to the arrest and conviction of those involved in the crime.

Adams Detective Agency of Atlanta, Georgia was hired to investigate and found that E. L. Golden, cashier of the Tallassee Falls Manufacturing Company, had withdrawn the money from the bank for the company’s Christmas payroll and deposited it into the safe in the main office. Considering that dynamite wasn’t used to access the vault and that Golden had a set of keys to the office and the vault, they concluded Golden was the culprit.

Within two weeks on January 5, 1921, authorities arrested Golden and place him under a bond of $10,000 on a charge of grand larceny. At his preliminary hearing on January 7, he entered a plea of not guilty. At the hearing, witnesses took the stand and it was discovered that Golden was not the only person with a set of keys to the office and vault, but four others in the company did as well. With the only evidence against Golden being circumstantial, the case was dismissed and he was released from custody.

Closure

In the 1960s, the oldest mill structures, known as Mill No. 1 located on the west bank of the river, ceased all operations. In 1991, Mill No. 1 was purchased by a consortium, which removed the window sash and gutted the five-story wooden interior structural system for commercial resale. Although the owners announced they would adaptively reuse the mill, the project never happened and the structures were abandoned. A central portion of the roof collapsed in 1999 during a thunderstorm due in part to the removal of the internal bracing. The falling roof trusses also took down sections of the upper floor in one part of the building. The East Mills operated continuously until 2005 when it was closed. At the time of its closure, the Tallassee Mills were the oldest continuously operating textile mills in the United States.

Salvaging of the mill’s Longleaf Pine

The property was sold to a Birmingham company called Process Knowledge in 2006. They deconstructed cotton warehouses on one end of the property to harvest the longleaf pine wood. It would later be purchased in 2016 by Mount Vernon Pine LLC which was created for the specific purpose of salvaging the wood.

When the Spanish first arrived in America in the 1500s, the longleaf pine ecosystem covered 60% of the land in the Southeastern part of the continent, encompassing nearly 90 million acres of land. Excessive logging took place throughout the 1600s, 1700s, and 1800s, with the lumber being used to build structures or ships, or cleared out to make way for cotton plantations. Longleaf pine was the timber of choice for construction during the Industrial Revolution due to its straight-grained properties making it extremely hard and durable. The dense grain made it possible for building large structures such as mills, bridges, trestles, and other industrial buildings. Due to its popularity, the timber was also commercialized and sold overseas. Longleaf pine lumber production peaked in the early-1900s due to World War I as vast acres of the longleaf pine in the southeast were cleared to aid in shipbuilding for the war effort.

Longleaf pine has since been declared endangered and as such, the only way to legally obtain the highly sought-after lumber is by recovering wood that has been left underwater or salvaging it from old buildings. The Hudsons bought the mill with the intent of deconstructing most of the mill and harvesting the wood and stone from the facility with the possibility of converting a part of the facility into a museum or housing.

Destruction of the East Mills

On May 4, 2016, the East Mills located on the east banks of the Tallapoosa River was destroyed in a fire. The fire was reported at 10:55 pm with more than 130 firefighters from 11 departments working throughout the night attempting to bring the fire under control. Due to the fact that the structure was vacant with no running electricity, and there were no reports of lightning in the area, the fire was deemed ‘suspicious’. The owners, Thomas Hudson, and his son, Thomas Hudson III, purchased the property a week prior to the fire and speculated that the fire was intentionally set due to their purchase of the site. According to the Hudsons, the mill had some of the best-preserved longleaf heart pine in the country.

Due to the extent of the fire, the Hudsons believe the fire was set in multiple locations throughout the facility to guarantee its destruction. Out of speculation, it could’ve been someone who didn’t want to see the facility deconstructed and shipped across the country and instead would see it all destroyed where it stood. It could’ve also been in a competing interest by someone who had thoughts of acquiring the mill or was unsuccessful and burned it down out of jealousy.

Locals believe neither of these theories and roll their eyes when asked about it. Despite asking the public for help including a reward for any information leading to the arrests of the perpetrators, no arrests have been made. Following the fire, the property was never properly cleaned up, so the city sued Mount Vernon Pine LLC in 2019 for public nuisance. The property was donated to the city in 2021.

Restoration of the Tallassee Armory

In comparison to the mill’s peak operation years, not much remains of what was one of the oldest textile mills in the nation and what was once the heartbeat of the town of Tallassee. The property on which Mill No.1 lies is owned by the Talisi Historical Preservation Society which have been slowly restoring the structures there which includes the Tallassee Armory. The goal is to someday move the historical society’s headquarters to the armory while transforming what remains of the textile mill building into an event venue.

Photo Gallery

References

The Tallassee Tribune, Carmen Rodgers. (April 26, 2019). The man who built Mount Vernon Mills

tallasseeal.gov, William E. “Bill” Goss. (retrieved May 23, 2022). A History of Tallassee

WSFA 12 News. (June 18, 2016). Owners believe Tallassee mill fire was intentionally set in multiple spots

Alabama News Network. (December 20, 2019). Tallassee Mill Destroyed By Fire in 2016 Will Soon Have A New Owner

Alabama News Network. (May 10, 2021). Tallassee Seeking Input on Burned-Out Mill Property

Tallassee Times, Michael Butler. (retrieved May 23, 2022). Tallasseee in Pictures: Mount Vernon Mills

The Montgomery Advertiser. (January 6, 1921). CASHIER OF MILLS UNDER $10,000 BOND; LARCENY CHARGE

The Montgomery Advertiser. (January 8, 1921). STATE FAILS IN CASE AGAINST CASHIER OF TALLASSEE MILLS CO.

The Selma Times-Journal. (December 23, 1920). Robbers Get $19,000 Cash at Tallassee