| City/Town: • Goodwater |

| Location Class: • Industrial |

| Built: • 1918 | Abandoned: • N/A |

| Status: • Abandoned |

| Photojournalist: • David Bulit |

Table of Contents

Jones Stephen Gilliland Sr.

Jones Stephens Gilliland was born on October 23, 1877, the son of Charles Henry and Sarah Elizabeth Stephens Gilliland. He attended the public schools of Goodwater and graduated with a bachelor’s degree from Auburn University, then known as the Alabama Polytechnic Institute. In 1906, he organized the Peoples Trust and Savings Bank and served many years as president and chairman of the board. He also founded the Goodwater Fertilizer Company in 1910. In 1918, he founded the Southern Casket Company as there was a high demand for caskets during the Spanish flu epidemic. He served as its president until his death on July 13, 1959.

Along with his extensive business ventures, Jones was also involved in local politics. He was chairman of the Coosa County Liberty Loan Committee; chairman of the War Savings Committee; member of the Committees of Red Cross drives; and mayor of the town of Goodwater. He was an elder in the Goodwater Baptist Church and held many church offices during his long membership. He also served as chairman of the Coosa County Board of Education and a trustee of the local high school. Jones believed that “Education is in a large sense a business enterprise” and that the County Board of Education should be conducted with the efficiency and economy of a successful business.

Joseph Forney Gilliland

After Jones’ death in 1959, ownership of the Southern Casket Company fell into the hands of his sons, Jones Stephens Jr. and Joseph Forney Gilliland. Joseph was born on September 4, 1927, in Sylacauga. He served in World War II and participated in the Occupation Forces in the South Pacific. After the war, he attended the University of Alabama and returned to Goodwater where he was employed at his father’s Peoples Trust and Savings Bank. Along with the Southern Casket Company, Joseph also operated the Hatchet Creek Golf Club located just outside of Goodwater.

In an account written in Chief Cook & Bottle-Washer: The Unconquerable Soul Of Wilkie Clark, Tommy Bridges, then-owner of the Southeastern Casket Company in Sylacauga, explained that his father Eugene Phelps “Slick” Bridges managed the Southern Casket Company for some time. Although he doesn’t state any dates, he mentions his father worked for the company for 48 years. Tommy also mentions that his uncle and cousins owned the company, along with “a bank, and a golf course,” which one can assume refers to Joseph Gilliland. It was said that Eugene Bridges helped black funeral directors such as Willie Clark, owner of Clark Funeral Home in Roanoke, by keeping their businesses stocked with caskets at a time when most casket suppliers had strict policies to not do business with black funeral homes.

Southern Casket Company

Founded in 1918, the Southern Casket Company was one of the largest industrial organizations in Coosa County. By the 1950s, its business area extended to the entire southeastern United States, as far west as Texas, and as far north as Indiana. The company operated out of a large 30,000 square foot factory known as the Casket Factory located in downtown Goodwater on Casket Street in close proximity to the town’s railroad freight depot.

Casket Assembly Process

The lumber used by the company was purchased from local sawmills and stored on company property until needed. Often the lumber needed drying before processing can start so a kiln was maintained on the property for this purpose. After drying the lumber, it’s transferred to the woodworking department where it is sawed, sanded, and formed into the basic parts of a casket. The parts are then taken to the shell finishing department where the caskets are assembled. Once assembled, the wood is inspected and sanded down even further to get the smoothest possible finish.

From there, the caskets are taken to the covering department where the caskets were then dissembled. A variety of fabrics are then glued to the wood, covering every major part of the casket before it is reassembled. The casket is then moved to the sewing department where it’s furnished with interior drapes and the casket bed is installed. The bed was made of wood wool and covered with cotton fabrics. The interior drapes were made of different fabrics including cotton, satin, crepe, and velvet. Once the casket leaves the sewing department, the interior of the casket is complete.

Installation of the exterior hardware was the last step. Southern Casket purchased handles, carrying bars, and other external trims from other businesses and did their own finishing.

Before transport, the casket was wrapped in brown paper to protect it during shipping. A shipping crate was constructed to only hold the casket but doubled as a burial box when needed. The caskets are then braced within the shipping crates and stacked for shipment. Although the factory was by the railroad depot, most of the caskets were shipped by truck by the 1950s as customers found it much more convenient to receive their goods this way. Trucks were able to deliver goods directly to the customers rather than having them pick up their goods at the freight depot.

Steel Caskets

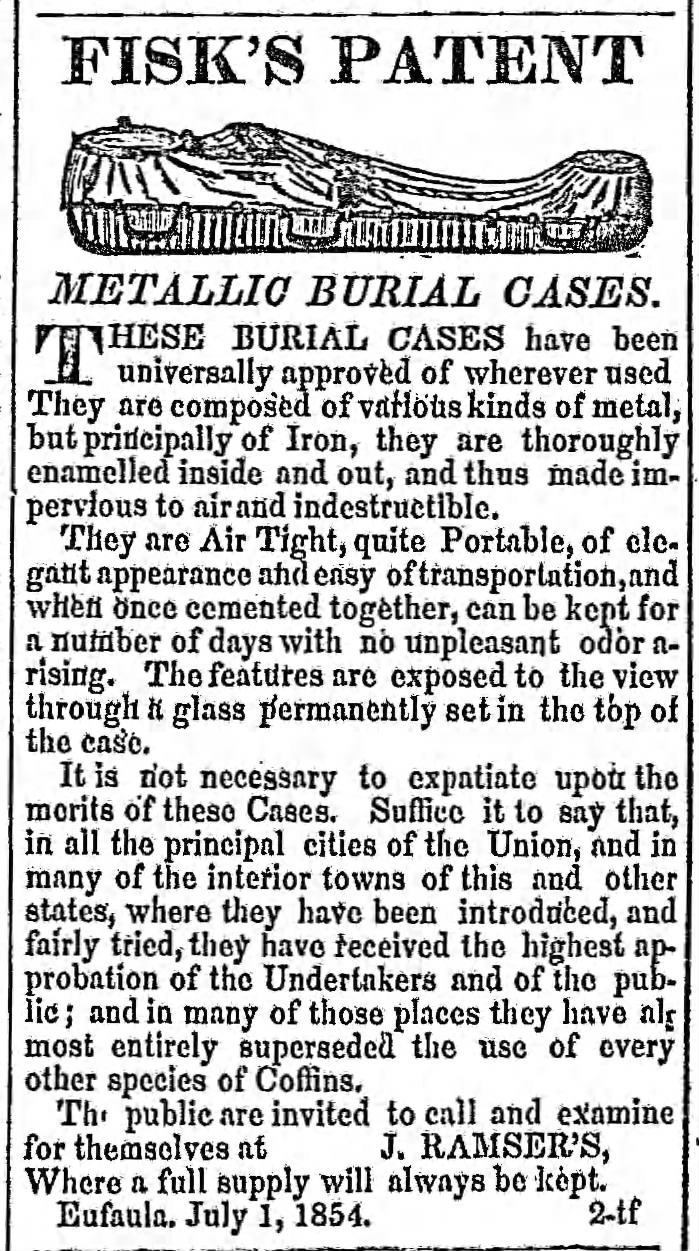

The first metal caskets appeared in the late-1840s when Dr. Almond Dunbar Fisk received a U.S. patent for a cast-iron coffin that he claimed was airtight and indestructible which he marketed under the name “Fisk’s Patent”. These bronze finish “burial cases” were custom-formed to the body featuring a lid with a plate of glass that allowed mourners to view the face of the deceased. While simple pine coffins at the time cost $2, a Fisk’s Patent burial case cost upwards of $100. These coffins were highly popular in the mid-1800s among wealthier families due to their potential to deter grave robbers.

As the coffins were airtight, they were valued for their potential to preserve the remains of individuals who died far from home as they could be shipped long distances. Multiple reports though indicated that gases generated by the decaying corpse became trapped within the coffin. The pressure built up from the trapped gases would then explode, shattering the glass, breaking the seals, and mangling and disfiguring the body in the process.

In 1918, the Batesville Casket Company in Indiana began making the first mass-produced metal-gasketed caskets called the Monoseal. The company developed a process that allowed for the mass production of metal caskets at a much lower cost than traditional wooden caskets. In the late 1950s, sheet metal became more readily available which increased the production of steel caskets across the country. According to the Casket and Funeral Supply Association, it was during the 1960s that steel caskets became favored by consumers for the first time.

With the wider availability of steel, other casket manufacturers sprung up in Goodwater such as Mayer of Alabama which opened in 1964 and operated out of a cinderblock building on the outskirts of town. Astral Industries, one of the largest casket manufacturers still in operation today, later purchased Mayer although they would end operations in Goodwater in the 1990s. FMP was another manufacturer operating out of the old National Guard armory located south of downtown on Armory Street. FMP would later be purchased to form the Goodwater Casket Company.

Despite the funeral industry shifting towards steel caskets, the Southern Casket Company continued making wooden caskets until the factory was shut down in 1974. As Bill Talton put it when he was interviewed for The New York Times, metal was simply cheaper than lumber. “You can build a dining room set out of the board feet of lumber you’d use to build a casket.” By the 1980s, the largest employers in Goodwater were no longer casket manufacturers, but instead were a lumber mill and a factory that made metal display shelves and checkout counters for supermarkets.

Goodwater Coffin Festival

On September 29, 1984, The New York Times published an article on the second annual Casket Carry and Fall Festival held in Goodwater. The event was formulated to inspire civic pride and bring in crowds while also celebrating the town’s peculiar heritage. The first festival was held the previous year and drew about 3,000 people to Goodwater, nearly double the town’s population. The festival was held annually well into the new millennium.

The festival’s highlight was the main event, “Race for a Coffin”. Nearly twenty teams of seven people usually made up of undertakers from across the region, competed in the “casket carry”. Six people carried the coffin, and one rode inside holding a glass of water. Teams raced through an obstacle course downtown, including a pile of sawdust and a mud pit, while the rider tried to spill as little water as possible. The winning team received a handmade wooden trophy of a miniature coffin with a blue ribbon attached to the lid.

Demise of Goodwater’s Casket Industry

In 2009, the Casket and Funeral Supply Association estimated less than a dozen manufacturers assemble more than 90 percent of all metal caskets sold in the United States. They also estimated that 70 percent of all caskets sold were manufactured by three companies; Batesville Casket Company, Aurora Casket Company, and York Group, which today is known as Mathews International Corporation. All of the casket manufacturers have since gone out of business or shut down operations. Much of the Southern Casket Company factory has been demolished and only a few structures remain for what was one of the largest industries in the county.

Photo Gallery

References

The New York Times. (September 29, 1984). TOWN PLANS MERRY WAKE FOR COFFIN-MAKING PAST

The Alexander City Outlook. (July 17, 1959). Last Rites Held Tues. For Founder Of Goodwater Bank

Who’s who in Finance, Banking and Insurance. (1926). Gilliland, J. S. pp. 375

The Rockford Chronicle. (March 13, 1936). J. S. Gilliland Writes To Voters On Candidacy

Assembly Magazine, Austin Weber. (October 2, 2009). The History of Caskets

The Enterprise-Chronicle. (August 16, 1956). Southern Casket Co. Covers Entire Southeastern Market

Haunted Ohio, Chris Woodyard. (March 19, 2015). A Grave Warning About Iron Coffins

Burials & Beyond, Kate Cherell. (July 1, 2019). Victorian Iron Mummies: The Fisk Casket