| City/Town: • Snow Hill |

| Location Class: • Educational |

| Built: • 1928 | Abandoned: • 2003 |

| Historic Designation: • National Register of Historic Places |

| Status: • Abandoned |

| Photojournalist: • David Bulit |

History of the Snow Hill Institute

Snow Hill Institute, also known as the Colored Literary and Industrial School, was founded in 1893 by Dr. William James Edwards, the son of formerly enslaved parents, as a private boarding school for African American youth in Wilcox County, Alabama. At the time, Alabama devoted only meager resources to the education of Black children. The school grew over time to include a campus of 27 buildings, a staff of 35, and over 400 students. Few of these buildings remain today. The Alabama Historical Commission recognized the school as a significant landmark in 1981, and it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on February 24, 1995.

Snow Hill, Alabama

Snow Hill’s history dates to around 1802, when the first settlers arrived from South Carolina. While most towns in Wilcox County, including Furman, were founded by settlers of Scottish, Irish, and English descent, some of Furman’s earliest residents came from South Carolina’s low country and were of French ancestry. In the early 1800s, the William Snow family established a homestead on a high hill north of what is now Furman, the site later known as Old Snow Hill Cemetery. The surrounding settlement became known as Snow’s Hill, a name it kept until 1872, when it was renamed Furman in honor of Furman, South Carolina. A new community was founded a few miles to the west and named Snow Hill.

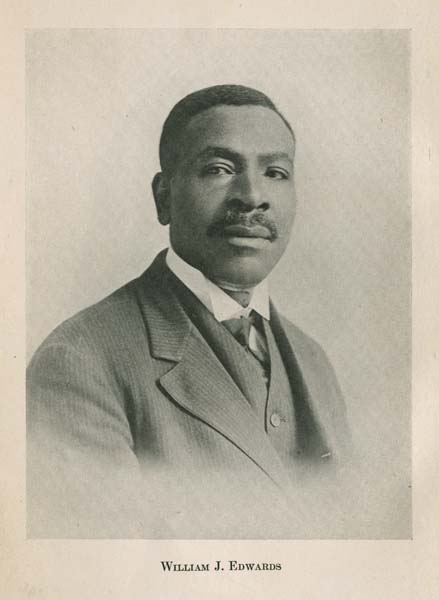

Dr. William J. Edwards, Founder of the Snow Hill Institute

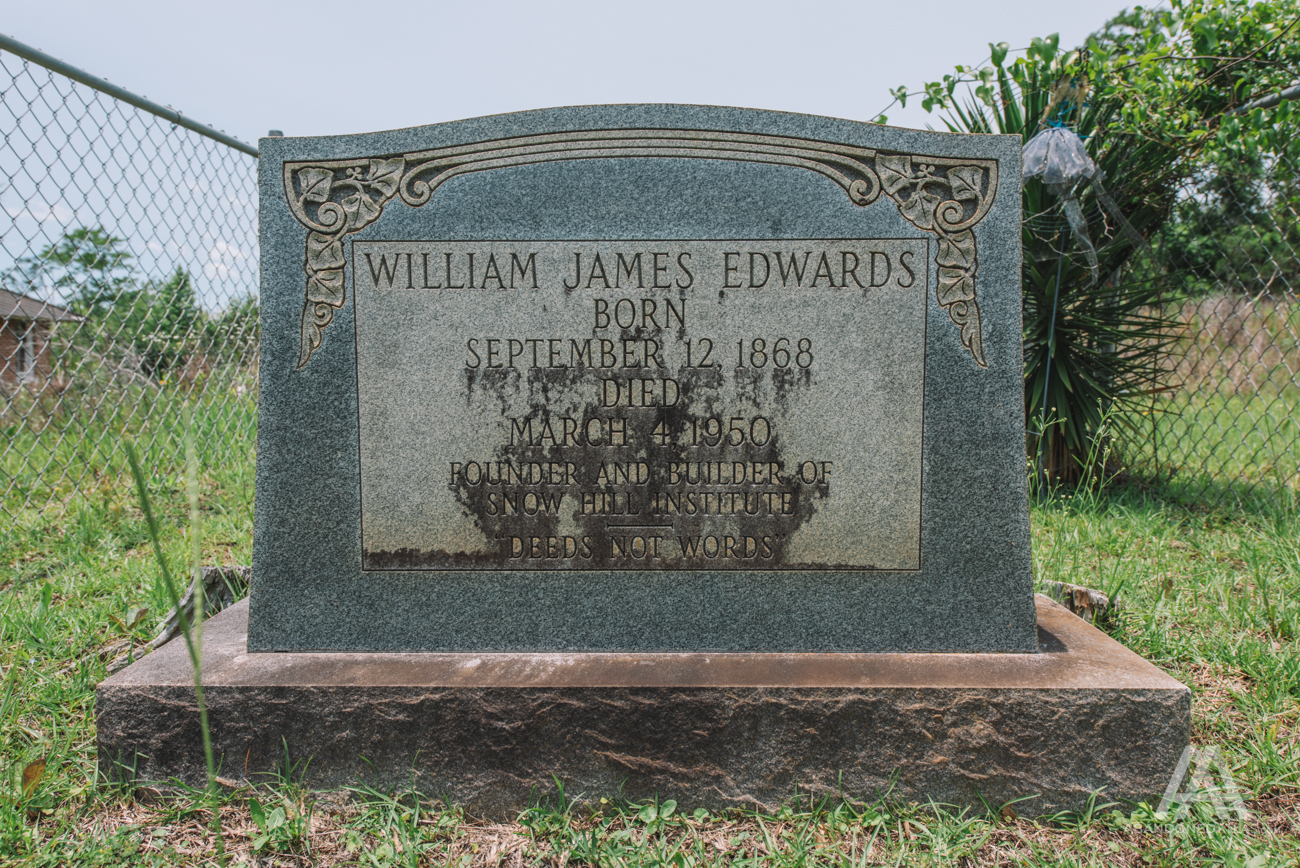

Edwards was born Ulysses Grant Edwards on September 12, 1868, on the Ransom Overton Simpson plantation located three-quarters of a mile east of where Snow Hill Institute now stands near the small community of Furman. Raised by his paternal grandmother and an aunt, he endured a debilitating childhood illness. His grandmother later renamed him William, and he added “James” in honor of his grandfather.

From an early age, Edwards labored in the cotton fields and worked as a sharecropper, eventually earning enough to pay off his medical debts. On January 1, 1889, at age 20, he entered the Tuskegee Institute under the leadership of its founder, Dr. Booker T. Washington. Unacquainted with basic table manners or the use of a toothbrush, Edwards nonetheless qualified for second-year classes in all subjects except grammar. For the first time in his life, he enjoyed three daily meals and a bed of his own. While working on Tuskegee’s farm, he listened each Sunday evening as Washington urged students to return home and uplift their communities. Edwards graduated in 1893, ranking second in a class of twenty.

Founding the Snow Hill Institute

Determined to bring educational opportunities to his native region, Edwards returned to the Alabama Black Belt, where more than 200,000 Black residents lived—over 40 percent of them of school age. In his 1918 memoir, Twenty-Five Years in the Black Belt, Edwards described these people as “ignorant and superstitious; that the teachers and preachers for the most part, were of the same condition.”

There was only one private school in the area that accepted Black students, and these schools often met in churches for terms lasting just two or three months each year. They had no access to public or private libraries. Edwards wrote, “Now, what can be expected of any people in such a condition? Can the blind lead the blind?” Seeing this as a dire injustice, Edwards set out to establish a school in the Snow Hill community, laying the foundation for what would become Snow Hill Institute.

In 1893, William J. Edwards returned to Snow Hill and found R. O. Simpson, owner of the plantation where Edwards was born, deeply concerned about the welfare of the local Black community. Simpson had known Edwards since infancy and often stopped to visit his grandmother while traveling through his land. After discussing Edwards’ vision for an industrial school, Simpson granted him seven acres on which to begin.

Edwards opened his first class in a deteriorating one-room log cabin on the Simpson plantation, teaching just three students with only fifty cents in operating funds. The following year, he constructed a two-room training building and hired two assistant teachers, both of whom were Tuskegee Institute graduates. Enrollment quickly grew to 150 students.

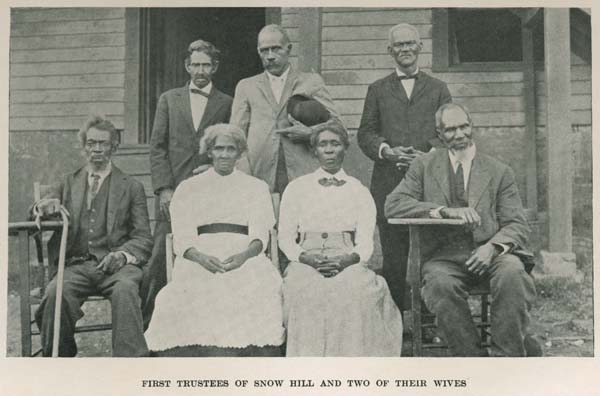

On June 15, 1895, two years after Edwards began teaching, the Colored Industrial and Literary Institute was formally incorporated. In 1904, the Board of Trustees, led by President R. O. Simpson, successfully petitioned to rename it the Snow Hill Normal and Industrial Institute. Serving not only Wilcox County but also attracting students from across the South and even from northern states, the school provided a full grade 12 liberal arts education alongside training in industrial and vocational trades, all without financial support from any religious or political organization.

Growth and Support

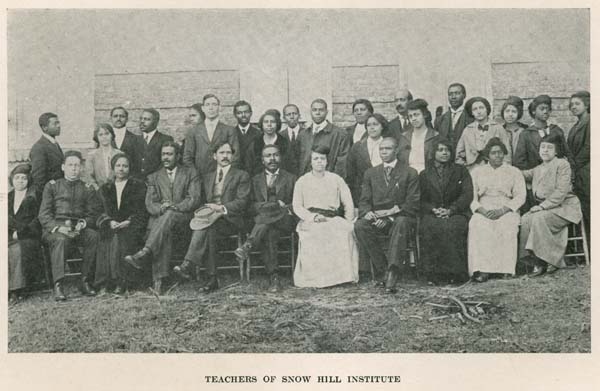

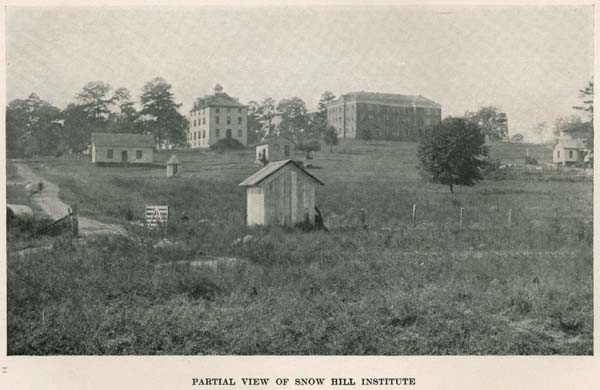

Edwards took on numerous roles: Secretary to the Board of Trustees, Chairman of the Financial Committee, Director of the Industrial Department, and professor of mental and moral philosophy as well as geometry. In just 25 years, what began in a rented log cabin with one teacher, three students, and fifty cents had grown into a campus of 24 buildings spread over 1,940 acres, serving 400 students, with a property value of $125,000.

William J. Edwards and his supporters steadily expanded the Snow Hill Institute’s land holdings, beginning with an initial gift of 100 acres from R. O. Simpson. In 1905, the school purchased seven acres from S. E. Mathews for $185. The following year, it acquired 12 acres from Rebecca Crook for $1,020 in February, and in November purchased 122 acres from W. H. Holtsclaw and his wife for $1,449. Both Holtsclaws were integral members of the school community—Mr. Holtsclaw served as board treasurer, sat on the financial committee, and taught bookkeeping and physics, while Mrs. Holtsclaw worked as the school’s copyist.

The school’s growth was made possible through local contributions and the generosity of prominent benefactors. Philanthropist and businessman Julius Rosenwald, founder of the Rosenwald Fund, contributed to Snow Hill as part of his mission to support vocational and technical education for African Americans. The Rosenwald Fund was also responsible for a nationwide building program of rural schools designed by architects of Tuskegee Institute became known as “Rosenwald Schools.”

In April 1906, during the 25th anniversary celebration of Tuskegee Institute, Edwards delivered a speech that caught the attention of industrialist Andrew Carnegie, who subsequently donated $10,000 to the Snow Hill Institute.

In 1908, R. O. Simpson and his wife sold 3,200 acres to the Snow Hill Institute for $30,000. The following year, the school sold 1,817 acres back to Simpson for $10,000. In his memoir, Edwards described the challenges he faced in acquiring the Simpson plantation. To secure the necessary funds, he made repeated trips to the North, relying on his powerful oratory to persuade wealthy white patrons to contribute. While these efforts often succeeded and forged lasting friendships, they also brought him moments of deep humiliation, rejection, and rebuke.

From the school’s earliest days, Simpson recognized Edwards’ dedication and supported Snow Hill through gifts of land and money. Throughout the institution’s history, a member of the Simpson family held a seat on the board, maintaining the family’s connection to the school.

Philosophies

The land served multiple purposes: portions were cultivated to provide food for boarding students, pastured for dairy cattle, and made available to members of the local Black community, many of whom still lived in former slave quarters on the Simpson plantation. Edwards envisioned not only a school but also a community of Black property owners and individuals who worked not only to better themselves, but also those around them. By 1907, Edwards had established this philosophy, which was expressed in his presentation to the Board of Trustees:

“We believe that the ultimate end of education for one people should be that of any people, Our purposes are to influence young men and women to go into the communities where they propose to work and, by precept and example, encourage the people to build better school houses and lengthen the terms; to influence the people to buy land and build dwelling houses having more than two rooms, and to bring about any needed reform that is essential to economic and upright living. Our ultimate end is character building; our books are not ends, but they are means to an end.”

When he founded Snow Hill, African Americans in the area collectively owned just 20 acres, and most worked as tenant farmers caught in cycles of debt. To promote independence, Edwards sold parcels of institute-owned land to local families for farming and homebuilding, often holding the mortgages himself. Deed records from 1919 to 1944 record at least 42 such transfers.

By 1918, Snow Hill Institute encompassed 1,940 acres, 24 buildings, and an annual enrollment of 300–400 students. Graduates went on to establish similar schools across the South. That same year, Edwards reported that Black landowners in the surrounding Black Belt now held more than 20,000 acres and were building improved homes, schools, and churches.

He also founded the Black-Belt Improvement Society to promote moral, mental, spiritual, and financial betterment. Open to anyone of good moral standing who wished to improve their circumstances, the society organized purchasing cooperatives, promoted thrift, encouraged homeownership, and disseminated farming and soil conservation knowledge. Advancement within the society was tied to property ownership, starting with modest holdings such as three chickens and a pig, and increasing with larger acquisitions.

Working Children

Students were taught real-world skills by working in various industries provided by the school, which also helped finance the school’s programs. This became a subject of contention among the parents of the children who attended Snow Hill Institute. Many forbade the school from “working” their children, stating that their children had been working all their lives and that they did not mean to send them to school to learn to work.

Not only did they forbid their children from working, but many took their children out of school rather than allow them to do so. The opposition was mostly made up of “illiterate preachers and incompetent teachers, who had not had any particular training for their profession,” and had never attended school.

Despite opposition, the school retained the “Industrial Plank” in its platform, steadily expanding its offerings until fourteen industries were in constant operation. Agriculture remained the foremost and foundational trade, reflecting the school’s location in a farming region where 95 percent of the population relied on agriculture for their livelihood.

Cultural Arts Program

Snow Hill Institute offered academic and vocational programs, placing strong emphasis on the cultural arts, especially music. To lead the school’s music department, Edwards hired Selma native and Tuskegee graduate Henry A. Barnes, who had pursued further study at the New England Conservatory. Barnes brought Alberta Simms to the faculty, and together they established a high musical standard at Snow Hill, introducing and performing works by African American composers such as Harry T. Burleigh and Nathaniel Dett alongside pieces by major European composers.

One of Simms’ pupils was Alberta Grace Edwards, the founder’s daughter. Showing early musical talent, she spent several summers as a teenager studying piano at the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston. After graduating from Snow Hill Institute, she continued her education at Fisk University and Alabama State University. Her first position was teaching music at Snow Hill during the 1920–21 school year.

In the summer of 1921, while attending Fisk, Alberta Edwards married Arnold W. Lee, a Tuskegee graduate who had joined Snow Hill in 1918 as an electrical engineer. The couple had seven children, and Alberta not only taught her own children piano but also gave lessons to children throughout the Snow Hill community. Students participated in daily assemblies and Sunday services where they sang traditional spirituals as well as Protestant hymns, fostering a sense of pride in their heritage and the accomplishments of African Americans despite the racial barriers of the time.

Most of the more than two dozen early campus buildings were built by Snow Hill students themselves—a system adopted from the Tuskegee Institute. In 1911, a fire destroyed three key structures—Messenger Hall (the dining hall and girls’ dormitory), Simpson Hall (a girls’ dormitory), and the commissary. In response, concerned citizens published a pamphlet, Snow Hill Institute: A Light in the Black Belt, endorsed by prominent individuals from New York, Boston, and beyond, to rally donations for rebuilding.

Robert R. Taylor, Pioneer Black Architect

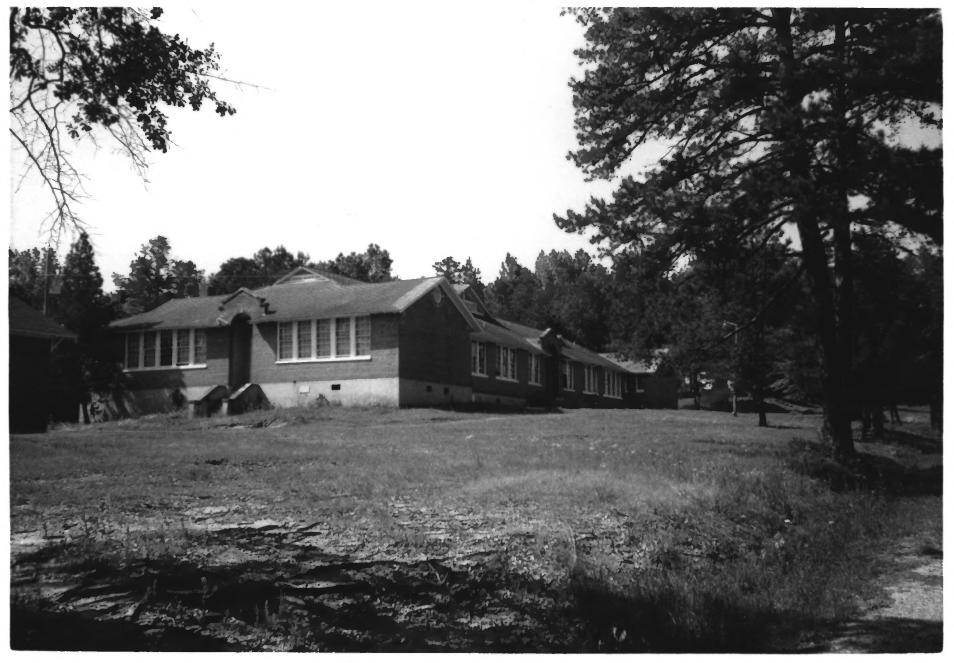

Edwards led the school until 1924, when ill health forced his retirement as principal. In 1925, Snow Hill merged with the State of Alabama and operated as a segregated public school. In 1928, the state purchased 10 acres at the heart of the campus for one dollar to build a county school. Wallace Buttrick Hall, designed by Robert Robinson Taylor, was completed in 1930 on the site of Simpson Hall. The Vocational Building, completed in 1926, occupied the location of the former Training Building–Elementary School.

Taylor was the first African American to graduate from the United States School of Architecture and, in 1892, became the first Black graduate of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Immediately after earning his degree, he accepted an offer from Booker T. Washington to develop the industrial program at the newly founded Tuskegee Institute and to design and oversee the construction of a new campus building.

From 1892 to 1932, Taylor was responsible for designing most of Tuskegee’s buildings, collaborating during his final decade with Louis H. Persley, a Carnegie Tech graduate. Taylor was also responsible for designing the Colored Masonic Temple in Birmingham, Alabama, a building historically significant to the Civil Rights movement in Alabama.

Closure

Despite his failing health, Edwards continued to travel and raise funds for Snow Hill until his death on March 4, 1950, and he was buried on the campus beside Wallace Buttrick Hall, the main school building.

After Edwards’ administration, the school gradually declined. The trade programs were discontinued, and several buildings, including two dormitories, burned to the ground. From 1928 to 1973, the Wilcox County Board of Education oversaw academic operations. Following the desegregation of the county schools, Snow Hill Institute closed in 1973.

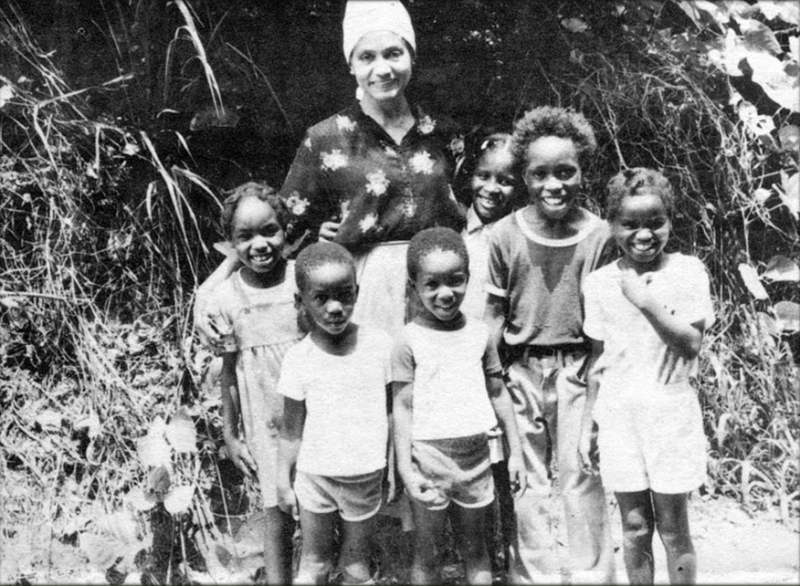

Consuela Lee, Founder of the Springtree/Snow Hill Institute for the Performing Arts

In 1979, Edwards’ granddaughter, jazz pianist and educator Consuela Lee, returned to Snow Hill to revive her grandfather’s vision. She canvassed the community to gauge interest, and when residents expressed support, she left her position at Norfolk State University to reopen the school as a performing arts center. Born November 1, 1926, in Tallahassee, Florida, to Alberta G., a classical pianist and William J. Edwards’s daughter, and Arnold W. Lee, a cornet player and band director at Florida A&M University.

When Consuela was three years old, the family moved to Snow Hill, where she began piano studies and quickly demonstrated prodigious talent, mastering Chopin’s etudes and other classical works. Her lifelong passion for jazz began when her father brought home Louis Armstrong’s 1927 recording of Struttin’ with Some Barbecue. She developed an enduring admiration for artists such as Nat King Cole, Oscar Peterson, Art Tatum, Dizzy Gillespie, Fats Waller, Mary Lou Williams, and Sarah Vaughan.

After graduating from Snow Hill Institute in 1944, Lee attended Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. There, she encountered Alfonso Seville, a Meharry Medical College student and gifted jazz pianist, who became a formative influence. In later years, Lee recalled that Black colleges of the time discouraged jazz in favor of European classical repertoire—but she and her peers played it anyway. She honored Seville’s mentorship decades later in her 2001 recording Piano Voices with the piece Prince of Piano – Alfonso Seville.

Lee graduated from Fisk in 1948 and began teaching music in Tallahassee. She earned her master’s degree in music theory and composition from Northwestern University in 1959 and pursued further study at the Peabody School of Music and the Eastman School of Music in the late 1960s. She also enjoyed memorable professional encounters, including an impromptu performance accompanying her idol, Sarah Vaughan, at a Newark nightclub.

Her career included directing the celebrated Phillis Wheatley High School Glee Club in Houston, Texas, during the early 1960s, and teaching at several historically Black colleges and universities, including Alabama State University, Hampton Institute, Talladega College, and Norfolk State University. In the early 1970s, she joined her siblings A. Grace Lee Mims, Bill Lee, and Cliff Lee to form The Descendants of Mike and Phoebe, a group honoring their enslaved ancestors through performances of spirituals and jazz on numerous Black college campuses.

Establishment of the Snow Hill Institute for the Performing Arts

By the late 1970s, disillusioned with the restrictions of college teaching, Lee resolved to return to Snow Hill, fulfilling a vow she had made at age twelve. In 1979, Lee canvassed the community to gauge interest in reviving the school. With strong local support, she reopened the campus as Springtree/Snow Hill Institute for the Performing Arts in the summer of 1980, emphasizing African American contributions to music, drama, and dance. The school operated from Wallace Buttrick Hall and the W. J. Edwards Memorial Library. In 1981, she also founded the Little Children’s School, housed in the school’s circa-1958 cafeteria building.

In 1980, a title search revealed that the Snow Hill Institute still held 1,465 acres under the management of a board of trustees. That same year, the National Snow Hill Institute Alumni Association was established to honor the legacy of founder William J. Edwards and to preserve the school’s historic buildings and grounds. Annual gatherings at the campus have been held ever since.

From 1980 to 2003, Snow Hill Day Celebrations became a fixture, attracting alumni, local residents, and nationally renowned artists such as Max Roach, Milt Jackson, Ruby Dee, and Delroy Lindo. In 1993, the institute’s centennial honored both its founding and the achievements of William J. Edwards in advancing educational opportunities for African Americans in Wilcox County, Alabama, and beyond. Among the 300 attendees was film director Spike Lee, Edwards’ great-grandson and Consuela’s nephew, who expressed interest in producing a film about the school’s origins.

Lee’s students achieved national visibility, most notably the vibraphone ensemble Bright Glory, which toured colleges, film festivals, and churches performing her jazz arrangements. In 1988, they appeared on WABC-TV’s Like It Is, hosted by Gil Noble.

Lee’s students, including a touring vibraphone ensemble called Bright Glory, performed her arrangements of jazz works by Duke Ellington and other noted composers at colleges, film festivals, and churches nationwide. In 1988, the group appeared on WABC’s Like It Is, hosted by Gil Noble in New York City. The performing arts program continued until 2003, when Lee’s declining health forced its closure.

Historical Recognition

The Alabama Historical Commission recognized Snow Hill Institute as a significant landmark in 1981, paving the way for its inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places in 1995, thanks in large part to Consuela Lee’s revitalization efforts. Of the original 27 campus buildings, less than a dozen remain, including Wallace Buttrick Hall, W. J. Edwards Memorial Library, and teacher cottages displaying architectural styles from Queen Anne to Craftsman.

Deterioration of the Former Snow Hill Campus

In September 2013, William J. Edwards’ former home was destroyed by fire; his grandson, Donald Stone, who lived there at the time, escaped unharmed. Plans were announced to rebuild the house and establish a center dedicated to the study of the rural school movement.

In 2016, vandals broke into the campus, smashing windows and causing thousands of dollars in damage. A nearby resident, alerted by the noise, recorded the license plate of a truck at the scene and contacted authorities. The four suspects, two juveniles and two adults, claimed they were “ghost hunting” but were arrested and charged with burglary and criminal mischief.

Today, little remains of Snow Hill Institute beyond a handful of vacant buildings scattered across an overgrown campus. Alumni still living nearby serve as informal caretakers, but the property has suffered roof damage from recent storms, vandalism, and preservation efforts have been minimal. The surviving structures stand as weathered reminders of more than a century of history, awaiting a plan to ensure their survival.