| City/Town: • Tuscaloosa |

| Location Class: • Medical |

| Built: • 1939 | Abandoned: • ~1977 |

| Status: • Abandoned |

| Photojournalist: • David Bulit |

Table of Contents

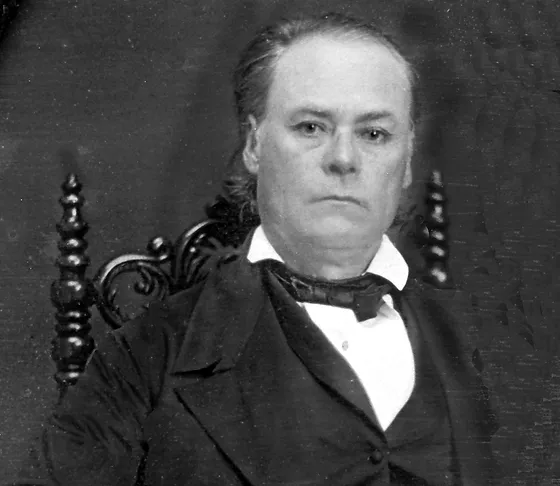

Robert Jemison Jr., Politician and Plantation Owner

The old Jemison Center in Northport, Alabama, is named in honor of Robert Jemison Jr., a prominent Alabama business magnate, politician, and staunch advocate for mental health. He was born on September 17, 1802, in Lincoln County, Georgia, the son of William and Sarah Mims Jemison.

He was educated at Mount Zion Academy, where he was a classmate of future senator Dixon Hall Lewis, and attended the University of Georgia. His father was a slaveholder and landowner of at least four large-scale properties. To differentiate himself from his grandfather, who was also named Robert, Robert Jemison Jr. adopted the suffix “Jr.” In 1826, he relocated with his father’s family to Pickens County, Alabama, where he became a planter until 1836 and moved to Tuscaloosa.

Jemison served in the Alabama state legislative between 1840 and 1851, initially in the Senate and then the House. He returned to the Senate from 1851 to 1863. In 1861, he opposed secession as a convention delegate. He was unanimously elected President of the Alabama Senate in 1863. Soon after, Jemison joined the Confederate States Senate, succeeding William Lowndes Yancey, who had died of kidney disease.

Jemison owned multiple businesses, including a stagecoach line, toll roads, toll bridges, grist mills, sawmills, turnpikes, stables, a hotel, and plank roads. His primary source of capital, though, was six plantations he owned in western Alabama, totaling 10,000 acres, the largest of which was the 4,000-acre Cherokee Place plantation in what is now Northport, Alabama. He had inherited the plantation from his father, which was then known as Crab Apple. Before building the Jemison-Van de Graaff Mansion in Tuscaloosa, he lived at Cherokee Place.

Cherokee Place

The name Cherokee came from a family tradition of Jemison’s wife, Priscilla Cherokee Taylor. Her family’s history shows that her parents befriended the local Cherokees when Priscilla’s mother nursed the chief’s daughter back to health after tribal medicines failed. The chief returned the favor by taking the Taylors into his village when the Choctaws “went on a rampage.”

The grateful Taylor family asked the chief how they could thank him for saving their lives. He replied by naming their first daughter “Cherokee.” Their daughter was already baptized as Elizabeth, so they named her Priscilla Cherokee when their second daughter was born in 1812. Robert and Priscilla had one daughter together, Cherokee Mims. Jemison also renamed the Crab Apple plantation to Cherokee Place. After her father’s death, Cherokee Mims inherited the large plantation and, in turn, donated the land to Bryce Hospital around the turn of the century.

Advocate for the Mentally Ill

Jemison advocated for creating a state-owned mental hospital known as the Alabama State Hospital for the Insane, which was renamed to Bryce Hospital. He hired renowned architect Samuel Sloan of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to design his house and the hospital. Sloan was responsible for designing Winter Place in Montgomery and many hospitals using the Kirkbride Plan, a model design for psychiatric hospital buildings used across the United States throughout the 19th century.

The Tuscaloosa Bridge Company was one of his well-known businesses. It built two of the first covered bridges across the Black Warrior River. Jemison hired Horace King, a skilled multiracial enslaved person from Russell County, to build bridges in eastern Mississippi. King became one of the most respected bridge designers and builders in the Deep South. In 1846, Jemison, along with King’s owner, John Godwin, obtained King’s freedom through an act of the Alabama Legislature.

The end of the Civil War and the collapse of the Confederacy and its economy also led to the collapse of Jemison’s vast fortune. He spent the remaining years of his life rebuilding his wealth. He devoted considerable time and attention to rebuilding the University of Alabama after it had been destroyed by fire in the closing days of the Civil War. On October 16, 1871, Jemison died at his home in Tuscaloosa.

The Jemison Center

The Jemison Center, named after Robert Jemison Jr., is located on what was originally Cherokee Plantation. It’s often referred to, and wrongly, as “Old Bryce.” In 1900, the Alabama Legislature established a mental health facility in Mount Vernon, Alabama, to relieve overcrowding at Bryce Hospital. This hospital became known as the Mount Vernon Hospital for the Colored Insane since it served African Americans exclusively until 1969, when it was desegregated following the Civil Rights Act of 1964. This hospital was renamed in 1919 to Searcy Hospital, named after Dr. James Thomas Searcy, superintendent of Bryce Hospital.

By the 1920s, Bryce Hospital was severely overcrowded again, and satellite institutions were created nearby to relieve the pressure, such as the Alabama Home for Mental Defectives, later known as Partlow State School. To further help relieve overcrowding at Bryce, the former plantation house at Cherokee Place was razed, and in its place, a three-story Neo-Classical brick institution was constructed. At the time, the asylum was called the State Colony Farm for Negroes, with Dr. William Dempsey Partlow Sr., superintendent of Alabama Insane Asylums, responsible for how it would be operated.

Before the Jemison Center was built, African American patients were sent 100 miles away to Searcy Hospital, which, from 1902 until 1939, was the only state facility serving African American patients.

Dr. Peter Bryce, superintendent of Bryce Hospital, believed that idle hands allowed mental patients too much time to focus on their condition. He pragmatically recognized patient labor as essential to the hospital’s economic survival in the face of diminishing state funds. He also demanded that patients be treated with courtesy, kindness, and respect at all times. Work programs and other activities, including farming, sewing, maintenance, and crafts, were encouraged.

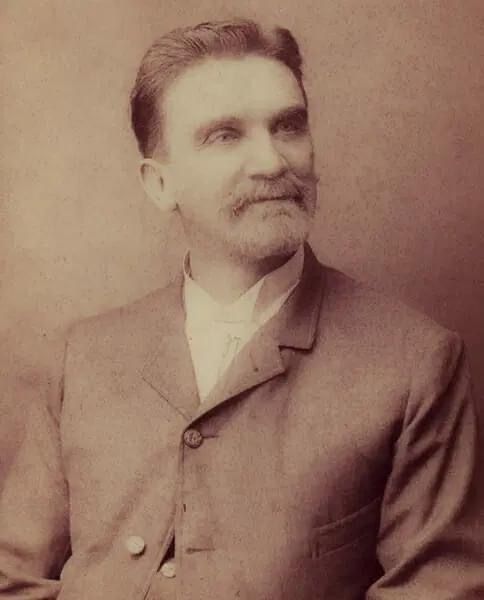

Dr. William D. Partlow, Eugenicist

Partlow was a physician at Bryce Hospital since his graduation on October 1, 1908, when he was appointed assistant superintendent of the hospital. He held this position until his election in 1919 as the successor to Dr. James T. Searcy. Partlow was a strong believer in Dr. Bryce’s teachings, writing such papers as “Value of employment and its relation to nervous and mental diseases,” and “Medicine and sociology, Their relation in the past and present.” He transferred this belief system to the Jemison Center, operating the asylum as a state work farm, where able-bodied African American patients would work the fields to produce food for the hospital, as well as perform other kinds of labor such as weaving, mending, etc.

Partlow was also a eugenicist and had the power to sterilize any patients without consent. In 1934, he proposed a bill that would allow for sterilizations of every patient upon release (something he was already doing), as well as forming boards of doctors that would design groups to be sterilized. The bill passed both houses of the Alabama legislature but was vetoed by Governor Bibb Graves. Partlow continued sterilizing patients until around 1945, when the tide was turning against eugenics due to its association with Nazi Germany. In all, 224 people were sterilized in Alabama. It can be assumed that patients at the Jemison Center were also subjected to sterilization.

In 1969, the Jemison Center was desegregated due to the passing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and became a dormitory for high-functioning patients from the Partlow State School. It was around this time that the public became concerned about the conditions at the state mental asylums as allegations of overcrowding, unsanitary conditions, and deaths became increasingly common. This was coupled with patients working the fields, which the public viewed as being equivalent to slave labor.

Inhumane conditions at state mental asylums

Alabama, at the time, ranked last among U.S. states in funding for mental health. Bryce Hospital at that time had 5,200 patients living in conditions that Montgomery Advertiser reporter Hal Martine likened the conditions at the asylums to Nazi concentration camps, mentioning his experiences covering war crime trials after WWII.

In 1970, Paul Davis, a reporter for The Tuscaloosa News, visited the Jemison Center and wrote, “Human feces were caked on the toilets and walls; urine saturated the aging oak floors; many beds lacked linens; some patients slept on floors. Archiac shower stalls had cracked and spewing shower heads. One tiny shower closet served 131 male patients; the 75 female patients only had but one shower. Most of the patients at Jemison were highly tranquilized and had not bathed in days. All appeared to lack any semblance of treatment. The stench was almost unbearable.”

Wyatt v. Stickney

One hundred Bryce employees, including twenty professional staff, were laid off. University of Alabama’s Department of Psychology members sought to file suit on behalf of the laid-off workers. Nevertheless, Federal Judge Frank M. Johnson determined that the courts lacked the authority to intervene for terminated staff. However, he did acknowledge the potential for a lawsuit advocating for patients whose quality of care had been impacted.

In October 1970, Ricky Wyatt, a fifteen-year-old who had always been labeled a “juvenile delinquent” and housed at Bryce despite not being diagnosed with a mental illness, became the named plaintiff in a class-action lawsuit. One of the employees laid off was his aunt, Mildred Hunter Rawlings, and together, they testified about intolerable conditions and “treatments” designed only to make the patients more manageable. The plaintiff class was expanded in 1971 to include patients at other asylums, including Searcy Hospital, Partlow State School, and the Jemison Center.

After 33 years, the case was finally dismissed on December 5, 2003, with the finding by Judge Myron H. Thompson that Alabama complied with the agreement. The standards elaborated in that agreement have served as a model nationwide. Known as the “Wyatt Standards,” they are founded on four criteria for evaluation of care: Humane psychological and physical environment, qualified and sufficient staff for the administration of treatment, individualized treatment plans, and minimum restriction of patient freedom. This became the longest mental health case in national history. The State of Alabama estimates its litigation expenses at over $15 million.

Closure

All farming operations at state institutions ceased in 1977. The Jemison Center was shut down around the same time. That same year, the S.D. Allen Intermediate Care Facility was built near the Jemison building, housing men and women 65 years or older with a primary mental illness and a medical condition that requires an intermediate level of nursing care. It was named after Squire Dalton Allen, the Director of Facilities for the Alabama Department of Mental Health from 1923 to 1977. The facility closed down in 2003. Since then, the entire property has been abandoned.

The decaying building once known as the Jemison Center has inspired hundreds of ghost stories and legends throughout the years. Although people have ventured out there for decades, police and local neighborhood watch patrol the area, looking for any trespassers.