| City/Town: • Cahaba |

| Location Class: • Disappearing Towns |

| Built: • 1819 | Abandoned: • c. 2000 |

| Historic Designation: • National Register of Historic Places (1973) |

| Status: |

| Photojournalist: • David Bulit |

Cahawba, Alabama: The Rise, Fall, and Legacy of the State’s First Capital

Cahawba (often called Cahaba) began as an undeveloped settlement at the meeting point of the Alabama and Cahaba rivers. On February 13, 1818, a commission at the old territorial capital of St. Stephens chose this site for Alabama’s first state capital, a decision that was officially approved on November 21st. Because the town was still only a plan on paper, the state’s constitutional convention temporarily met in Huntsville until a proper statehouse could be built.

By October 1819, Governor William Wyatt Bibb announced that the town had been surveyed and lots were ready to be auctioned. Surveyors Willis Roberts and Benjamin Clements, hired for $730, laid out a town plan that incorporated the earthworks of a long-abandoned Native American settlement. The layout followed a grid pattern: streets running north to south were named for trees, while those running east to west were named for prominent men.

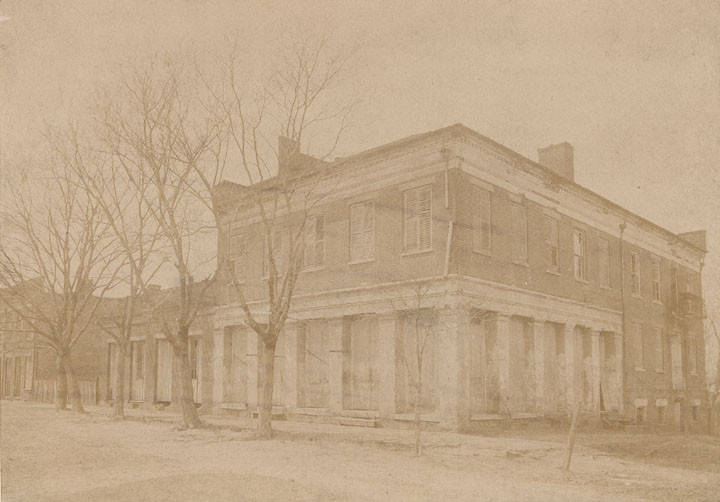

In May 1819, only months after statehood, 182 town lots were auctioned, bringing in an impressive $123,856, nearly a third of it paid in cash. These funds helped finance the construction of Alabama’s first Statehouse, with the remainder put into the state treasury. The new statehouse, a two-story brick building measuring 43 by 58 feet, stood near the corner of Vine and Capitol streets. By 1820, Cahawba was functioning as the state capital.

Its low-lying location, however, created serious problems. Seasonal flooding was common, and the area’s swarms of mosquitoes spread diseases such as malaria, yellow fever, and cholera, then believed to be caused by “bad air,” or miasma. These health concerns became key arguments for critics who wanted the capital to be moved. In January 1826, the legislature voted to relocate the seat of government to Tuscaloosa. Many residents left, some of whom chose to dismantle their homes, leaving empty lots behind.

A Second Boom as a Cotton Port

For several more decades, Cahawba continued to serve as the county seat of Dallas County. Thanks to the profits of the cotton trade, the town rebounded after losing its role as the state capital and once again became a thriving social and commercial hub.

Situated in the heart of Alabama’s fertile “Black Belt,” Cahawba grew into a key distribution center for cotton shipped down the Alabama River to the port of Mobile. Wealthy planters and merchants built impressive two-story mansions as symbols of their prosperity. Among the town’s notable buildings was St. Luke’s Episcopal Church, constructed in 1854 and designed by the nationally recognized architect Richard Upjohn, although Upjohn was not directly involved.

The arrival of the railroad in 1859 sparked a building boom, and by 1860, Cahawba’s population had reached about 2,000. Roughly 64 percent of its residents were African American. Across Dallas County, about three-quarters of the population was Black, most of them enslaved laborers working on cotton plantations.

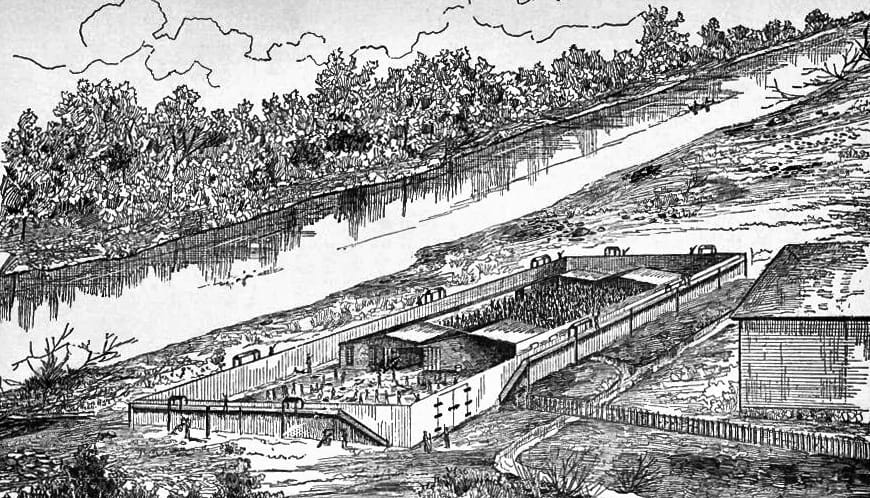

Cahawba During the Civil War: “Castle Morgan”

During the Civil War, Cahawba became the site of a Confederate prison camp known as Cahaba Prison, but more popularly called “Castle Morgan.” The facility originated in 1863 when Confederate authorities converted a cotton warehouse owned by Joseph Babcock into a prison. The warehouse, constructed in 1860 for storing and shipping cotton, stood along Arch Street on a bluff above the Alabama River. Surrounded by a hastily built stockade, the prison was intended to hold about 500 Union captives, but the number of inmates soon grew far beyond its capacity.

By August 1863, roughly 660 Union prisoners were held there, and after General Ulysses S. Grant suspended formal prisoner exchanges, the population surged. By the end of 1864, more than 2,100 men were crammed into the enclosure as prisoners were transferred here from Andersonville Prison in Georgia to prevent their capture during Sherman’s March to the Sea. By March 1865, the number exceeded 3,000, despite the warehouse measuring only about 125 by 200 feet and offering just 432 bunks.

Daily life was harsh: the water supply was unsanitary, flooding and disease that plagued Cahawba since its establishment were a constant threat, and there was only one fireplace to heat the crowded space. Food, clothing, and medicine were chronically scarce, and fleas plagued the men. Yet, compared to other Civil War prison camps, the mortality rate was remarkably low, with only about 142 to 147 men, roughly 2 percent, dying, thanks in part to the relatively humane conduct of the commandant and prison surgeon.

By March 1865, Confederate authorities began evacuating the prison. Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest and Union General James H. Wilson met in Cahawba at the Crocheron Mansion to discuss an exchange of prisoners captured during the Battle of Selma. A formal prisoner exchange occurred near Vicksburg on April 9, 1865, the same day General Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox. Many former Cahawba inmates were placed aboard the steamboat Sultana to return north, only to perish when the vessel exploded on the Mississippi River in one of the worst maritime disasters in U.S. history.

Postbellum

In 1866, the state legislature relocated the Dallas County seat to nearby Selma, and businesses and residents quickly followed. Within a decade, many of Cahawba’s houses and churches were dismantled and moved elsewhere. St. Luke’s Episcopal Church, for example, was taken apart and reassembled in 1878 at the small village of Martin’s Station.

During Reconstruction, Jeremiah Haralson, representing Cahawba and Dallas County, achieved a remarkable political career. He became the only African American in Alabama to serve in the State House, the State Senate, and the United States Congress.

As the town declined, most freedmen and the remaining white residents moved away. By 1870, the population had fallen to just 431, with 302 of those residents Black. Freedmen active in the Republican Party used the empty county courthouse as a meeting place to preserve their hard-won political rights. Many families turned vacant lots into small fields and gardens, but this effort was short-lived, and they too eventually left.

Before the turn of the 20th century, a freedman bought most of the old town site for $500. He demolished the remaining abandoned buildings, selling the salvaged materials by steamboat to Mobile and Selma to supply those growing cities. By 1903, nearly all of Cahawba’s buildings were gone, and only a few structures survived into the 1930s. Although the area is no longer inhabited, the Alabama Historical Commission maintains the site as Old Cahawba Archeological Park, which was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1973.

Fambro-Arthur House

William W. Fambro (sometimes spelled Fambrough) was born in 1805 in Davidson County, Tennessee. By the time he was ten, he had lost both parents and was placed under the care of a guardian. In exchange for his work, this guardian raised and trained him until he reached legal age. The guardian worked on riverboats, which may explain how young William eventually found his way to the busy river town of Cahawba.

When William arrived, Cahawba was thriving as the state capital. When the town was largely abandoned after the capital moved to Tuscaloosa, William chose to stay. During his early adult years, when the capital was still in Cahawba, he became acquainted with the many attorneys who kept offices along the main street near the courthouse. He secured an apprenticeship with a local lawyer, and by 1832, records show that he had opened his own law practice in town.

In 1839, he contributed to building the town’s first church. The following year, he purchased lots 9–12 and built a residence for himself, although it is believed that a portion of the home was an extension of an existing structure.

William married Elizabeth Jacob in 1842, and the two became deeply involved in community life. William served as Justice of the Peace in 1838 and 1841, as well as town constable, while Elizabeth, a former teacher, remained active in education. Both served on the board of trustees for the Boys & Girls Academy, located a block from their home. Though they had no children of their own, they opened their house to rural students, teachers, and principals who needed lodging during the school term.

By 1850, newspaper accounts reported that William had expanded his ventures to include a thriving sawmill, turning out pine, white oak, hickory, beech, poplar, and cedar for cabinetmakers and builders. The business prospered but demanded constant attention, prompting William and his wife, Elizabeth, in 1853 to move about six miles outside Cahawba to be nearer to the mill. That August, he placed an advertisement offering his townhome for sale, describing it as:

“Large and conveniently constructed, having 12 rooms beside a hall, 2 porticoes, and a back gallery. All the necessary outhouses are attached, including a fine garden, an orchard, and a house lot. The place is handsomely decorated with shade trees and ornamental shrubbery. An artesian well is now being drilled.”

In the years leading up to and during the Civil War, the house passed through the hands of several families, including the Troys, Williamses, Portises, and Bells. The last occupants of the home were the family of Ezekiel Arthur. Born into slavery in Arkansas in 1854, he was separated from his mother at age three and brought to Cahawba, where he appears in 1857 baptismal records as the “child servant” of Mrs. Arthur at the Episcopal Church. Sold multiple times before emancipation, and given different names with each sale, he finally adopted the surname of the last family who enslaved him, a common practice among freed people.

After the Civil War, Ezekiel spent nearly two decades searching the South for his mother and sisters. Around 1894, he returned to Cahawba, reportedly with some of his siblings, and purchased the old Fambro house for $2,000. By then, most white residents had left, and freedmen formed the majority of the town’s population. Ezekiel married Mary and became a prosperous farmer and landowner. With his son Sam, he raised corn, cotton, and sugar cane, producing syrup for local cafés. They owned their own mules, operated a hay press and a mill, and maintained a self-sufficient farm.

After Ezekiel’s death, Sam continued the work. In 1944, he married Mattie of Selma, and they raised two daughters in the house. Sam died at sixty-eight, but Mattie remained until she died in 1995 at the age of eighty, leaving the house unoccupied for the first time in more than a century.

St. Luke’s Episcopal Church

Upon entering present-day Cahawba, one of the first structures to be found is the St. Luke’s Episcopal Church. Built in 1854 during Cahawba’s antebellum boom, St. Luke’s originally stood on Vine Street near the intersection of Vine and First South Street. After the Civil War and Cahawba’s decline, the church was dismantled in 1878 and moved about eleven miles to the village of Martin’s Station, where it was reassembled and served an Episcopal congregation for several decades. The building originally had a square bell tower on the corner to the left of the current main front entrance, but this was not rebuilt when the church was relocated.

It later became home to an African-American Baptist congregation for more than sixty years before eventually being acquired by the Alabama Historical Commission. St. Luke’s was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on March 25, 1982.

In 2006–2007, students from Auburn University’s Rural Studio program carefully dismantled the building so it could be returned to Cahawba. From 2007 to 2008, they reassembled it near the corner of Beech Street and Capitol Street, across from the Old Cahawba Archaeological Park visitor center. This third location was chosen because the church’s original Vine Street site lay in a floodplain. By late 2009, most of the exterior restoration work was complete.

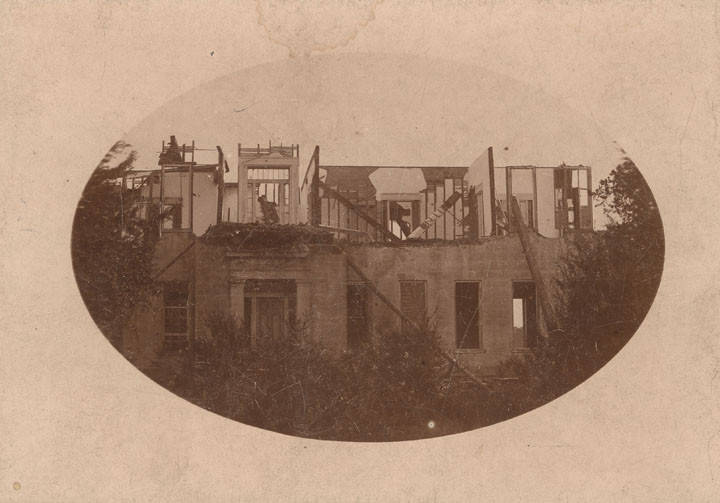

Crocheron Columns

By the 1820s, John Jay Crocheron had moved to Alabama, where he was elected as one of 12 directors for the Bank of Alabama in 1823 when the bank was located in Cahawba. There, he established a successful mercantile business and engaged in various commercial enterprises in Mobile, including owning a number of steamships. By 1840, Crocheron transferred the running of his mercantile business in Cahawba to his half-brother Richard Connor Crocheron and moved to Richmond in Dallas County, where other relatives had settled, and established Elm Bluff Plantation.

Comprising more than 5,000 acres, John Crocheron’s plantation was the largest in the area by far. It featured a boat landing, docks, warehouses, and elevators that serviced the steamships on the Alabama River. In 1845, he built a large, three-story Greek Revival-style house, which still stands today at the site of the former plantation.

Richard Connor Crocheron built a brick home that featured massive columns on the front and a side portico on what was known as “Crocheron Row,” which was the main business district in Cahawba. The back wall of the house adjoined a brick store that his uncles had built twenty years earlier. As Crocherons had also invested in a line of ocean-going steamships, Richard’s family was able to escape the Southern heat by returning North each summer to “take the waters” at Saratoga, New York. Following the death of his wife, Anna Maria Geib Crocheron, he sold his property at Cahawba and returned to New York with his three small children.

Shortly after the Battle of Selma during the Civil War, Union General James Harrison Wilson traveled to Cahawba under a flag of truce to negotiate a prisoner exchange with Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest. At the time, Colonel Thomas W. Matthews resided in the Crocheron mansion, situated near the Confederate prison camp known as “Castle Morgan,” and offered his home as the meeting place. Despite being a wealthy planter and slaveholder, Matthews had never wavered in his loyalty to the Union.

On April 8, 1865, Wilson arrived at 11 a.m., and Forrest followed at 1 p.m. The two generals first enjoyed a “bountiful Southern dinner” hosted by Matthews, after which they retired to the parlor for a long but cautious discussion. Having taken the measure of one another, they parted amicably, each prepared to continue the conflict. The very next day, General Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox, although the war would wage on for another month.

Following the decline of Cahawba after 1865, the old Crocheron home fell into disrepair and eventually burned down on December 20, 1923. All that remains of this mansion today are the brick columns known now as the “Crocheron Columns.” They were part of the side portico on the house.

Perine Artesian Well

Edward Martineau Perine was a Staten Island–born merchant and planter whose business success and grand estate made him one of the most prominent figures in Old Cahawba. Born on July 31, 1809, in Richmond County, New York, he was the son of Edward Perine and Addra Guyon Perine and descended from Daniel Perrin, the French Huguenot settler known as “the Huguenot.”

In the early 1830s, he left New York and settled in Cahawba, where he quickly established himself as a leading merchant. By 1832, he was in business with Thomas Moreng and Richard Conner Crocheron as Thomas Moreng & Co. After Moreng’s death in 1835, the partnership was reorganized, and Perine and Crocheron continued to operate the mercantile firm until Perine purchased Crocheron’s interest in 1850.

Three years later, he sold the enterprise to Samuel M. Hill and John R. Sommerville, but in 1856, he returned to commerce in partnership with Sommerville as E. M. Perine & Company. When that partnership dissolved in 1858, Perine continued with Sommerville as a salesman and, by 1860, entered a new partnership, Perine & Hunter. Anna M. Gayle Fry, writing in her book Memories of Old Cahaba, describes Perine as “a merchant prince of ante-bellum days, a Northern gentleman of the old school who was universally beloved by all who knew him.”

Perine’s wealth allowed him to become a planter and landowner and to commission one of the most impressive residences in the Black Belt. In 1856, he purchased a large brick factory building on Vine Street and hired architect John G. Snediker to transform it into a twenty-six-room mansion. The first floor included twin parlors, a grand dining room, a sitting room, a library, and spacious entry halls, while the second floor contained bedrooms and nurseries. An attached wing accommodated the kitchen, laundry, and servants’ quarters.

The landscaped grounds boasted conservatories and vineyards and featured an extraordinary artesian well, then considered one of the deepest in the region, between 700 and 900 feet, capable of producing about 1,250 gallons of water per minute. Water from the well was piped into the house and circulated through vents, creating what was widely described as a primitive form of air-conditioning, making it the first air-conditioned home in Alabama.

Tensions arose following a series of recent robberies in Cahawba and the suspicious burning of several houses, acts that even the most level-headed believed to be deliberate arson. Suspicion soon focused on a man named Pleas, a formerly enslaved Black man known for his notorious behavior. He had once belonged to Perine, who eventually sold him to John Bell because of Pleas’s uncontrollable conduct.

John Bell and his son John A. Bell were both killed, and the survivors were exonerated in a court of law. Both were buried together with the inscription on their gravestone reading, “No murderer hath eternal life abiding in him.” Alabama Department of Archives and History

Perine married twice. His first wife, Mary Eliza Snow of Providence, Rhode Island, whom he wed in Milledgeville, Georgia, on September 13, 1836, died in Cahawba two years later from complications of childbirth, leaving one daughter, Mary Eliza Perine. On August 6, 1846, he married Frances E. “Fannie” Hunter of Conecuh County, Alabama, daughter of Judge John Starke Hunter and Theodesia James Hunter. They had four daughters: Sarah Hunter (“Sally”), Addra A., Frances Hunter (“Fannie”), and Anna Hunter, though two died in childhood.

The Civil War and its aftermath devastated Cahawba and ruined many of Perine’s business interests. His daughter Mary later recalled that the family “lost all,” a fate shared by much of the planter-merchant class. He died on June 5, 1905, and was buried in the Presbyterian Cemetery at Pleasant Hill in Dallas County, Alabama, where his second wife, who died in 1910, also rests. Today, the Old Cahawba Archaeological Park preserves the site of his remarkable artesian well, known as the Perine Well.

Barker Slave Quarters

Samuel McCurdy Kirkpatrick enlisted in a Confederate cavalry unit at Cahawba on August 29, 1862, and served throughout the Civil War. Before the war, he had been a farmer and a maker of cotton gins. His wife, Sarah Catherine West, gave birth to their first child, Clifton, in April 1863, naming him after Samuel’s partner in the cotton gin business. In the years after the war’s end, Samuel and Sarah purchased a large brick mansion with extensive outbuildings on the northern edge of Cahawba.

Built in the early 1860s by Stephen “Shoestring” Barker, the complex included a two-story residence, two additional two-story structures in the rear, a two-story hexagonal privy, and a large barn. Barker, who ran a hotel in Cahawba and invested in railroads and other businesses, is said to have spent between $25,000 and $30,000 to build it, making the mansion a symbol of the town’s prosperity before the Civil War.

Behind the main house stood a rare two-story brick building used to house enslaved workers, something even the richest slaveowners rarely built. By 1860, about 60 percent of Cahawba’s people were enslaved. Census records show that Barker owned five enslaved people in 1850, and that number had grown to twenty-five by 1860. These men and women likely lived in the brick quarters Barker put up during that time.

Like many homes in the area, the mansion was abandoned after the county seat moved to Selma, and when Stephen Barker died in 1867, the mansion was sold at auction. This property became home to three generations of the Kirkpatrick family. As the town of Cahawba declined, the Kirkpatricks acquired many of the abandoned lots, and by the 1890s their farm stretched across much of the old town.

Their son, Samuel, became an eye, ear, nose, and throat specialist and was a founding physician of Selma’s Vaughan Memorial Hospital. Louise married and moved away. Herbert, the youngest, drowned in the Alabama River in 1879 at age ten and was buried in the town cemetery at the foot of Oak Street.

The eldest son, Clifton, remained in Cahawba and worked beside his father to build the agricultural enterprise that became known as Kirk-View Farm, a model of diversified agriculture. In 1889, he married Lida Lawhon. When Samuel and Sarah moved to Selma, Clifton took full charge of the family’s land and operations. Lida’s untimely death in 1893 left Clifton a widower at thirty, caring for their three-year-old daughter, Alma. Lida was buried alongside young Herbert in Cahawba’s “New Cemetery.”

On October 23, 1895, Clifton married Minerva Graham, daughter of Hamilton Claverhouse Graham of nearby Tasso. The next thirty-five years marked the golden era of Kirk-View Farm. Clifton and Minerva’s children were Mabel (1896), Graham (1901), Earl (1903), Samuel McCurdy (1906), Mary (1908), and Clifton Jr. (1911). Earl died in infancy, and Mary at age nine. The surviving children attended school in Selma, spending their weekdays with their two widowed grandmothers.

Building on his father’s work, Clifton expanded the operation to 10,000–15,000 acres of cotton. Yet he recognized the danger of the South’s one-crop economy and became an early advocate of diversified, scientific farming. He bred Poland-China hogs, maintained a dairy, raised cattle, and bred saddle and harness horses. In 1902, he began planting pecan trees; by the end of World War I, his 300-acre pecan orchard was thriving, many trees of which still stand. His foresight was vindicated when the boll weevil devastated Alabama cotton in 1914. Clifton died of pneumonia in February 1930 at age sixty-six.

When the mansion burned in 1935, a Kirkpatrick grandson converted the former slave quarters into a family residence by adding columns and constructing a back wing. Since the columns weren’t original to the building, they were removed in 2017.

St. Paul’s African Methodist Episcopal Church

Located just off Oak Street are ruins that mark the site of what was once the Methodist Episcopal Church South, built in 1849 as the first church in Cahawba dedicated to a single denomination. Before its construction, an earlier church built around 1840 served worshippers of all faiths, and prior to that, public services were held in Alabama’s Statehouse or the Dallas County Courthouse.

The land for the Methodist church was donated by William Curtis, one of Cahawba’s earliest and most respected citizens, even though he was not a member of the congregation at the time. The church’s first minister, Rev. James L. Cotten, soon became enamored with Curtis’s youngest daughter, Lucy.

Curtis strongly opposed the match, citing Cotten’s “want of education, indolence, excessive levity, transient life, and manners,” and even objected that the minister had previously “paid attentions to Miss Brown!” Despite her father’s misgivings, Lucy ultimately accepted Rev. Cotten’s proposal, and the two were married on March 7, 1853.

During his first year in Cahawba, Rev. Cotten led a congregation of eighty-three white members and about one hundred and fifty African Americans. Initially, services for the enslaved were held beneath the floor of a cotton warehouse. Before long, Cotten secured a nearby lot where the Black congregants could build a simple log church of their own, though worship there, as elsewhere in the antebellum South, remained under the supervision of a white minister.

After the Civil War and emancipation, Cahawba’s African American residents sought a house of worship that truly belonged to them. They organized an African Methodist Episcopal congregation, and since most of Cahawba’s white Methodists had by then moved away, the new A.M.E. congregation was able to take over the vacated Methodist Episcopal Church South. From that point forward, the building became known as St. Paul’s African Methodist Episcopal Church.

In 1954, sparks from a nearby woods fire set the wooden steeple ablaze. By the time fire crews arrived, the flames had weakened the structure so badly that the brick walls collapsed. In the end, only seven worshipers remained in the congregation.